“But Ol’ Man River, he jes’ keeps rollin’ along.”

— Joe, Show Boat, 1927

Last time, you recall, we did a little ruminating on the latest of the four great addresses ever given that define the nature of Princeton, and its role and charge as a great American university.

All right, since you ask, the first was waaaay back in May 1776 when, six months ahead of the advancing British army, the Rev. Dr. John Witherspoon ascended the pulpit in Nassau Hall to give the first political sermon of his tenure after eight years in America, “The Dominion of Providence Over the Passions of Men.” The second was the address at the Sesquicentennial Charter Day celebration in October 1896 given by then-professor Woodrow Wilson 1879, known ever after as “Princeton in the Nation’s Service.” The third, which we also noted a few years back, came in the subtle guise of a senior class dinner in March 1954; but it was delivered by one of the great global minds and even greater writers ever produced at Princeton, Adlai Stevenson 1922. A stern warning in the midst of rising Soviet power and McCarthyism, it is entitled simply “The Educated Citizen,” and is essentially an intellectual call to arms for the University and its community. And our recent topic, the fourth, was our beloved Toni Morrison’s address, 100 years following Wilson’s, at Charter Day in October 1996, in which her gift of bringing history alive flowered, and the resulting “The Place of the Idea; The Idea of the Place” urged us all to continue innovating in the longstanding tradition of the University, to guard against and overcome the dark and venal impulses of humankind.

And it’s worth mention that President Eisgruber ’83, noting Morrison’s recent death, summarized that address to the incoming Class of 2023 in much the same way at Opening Exercises Sept. 8 in the Chapel. He also took her idea to a personal level for the freshmen, by which all of us can profit: “You cannot really learn or grow if everything is always comfortable.”

I mention this to set the table for contemplation of another great Princetonian, one whose published works and persona were never the stuff of Nobel Prizes, enshrinement as a Founding Father, or qualification for the presidency. But in a time of unceasing change and high stress at the University, he made the great ideas of these great messengers come alive by living them himself every day, and by enhancing them with bright colors, with song, and with a knowing wink. As surely as we would not be a great university without the likes of John Witherspoon, Woodrow Wilson, Adlai Stevenson, or Toni Morrison, we would not be Princeton without Fred Fox ’39.

If this seems a bit of a leap to you, let me explain that I began all this by reexamining yet another address — for maybe the 10th time — and only realizing at long last that in it lay the very same transcendent ideas that inspired the first four, only in the same holistic, often downright joyous way that Fred himself did. The address was President Bill Bowen *58’s eulogy for Fred in the Chapel on Feb. 25, 1981. It is well worth remembering here and understanding thoroughly because, while we can’t all be like Toni Morrison every day — well, I can’t, anyway — we can all take a stab at being Freddie Fox, or at least how he most often appeared to us. And we might find the results surprising.

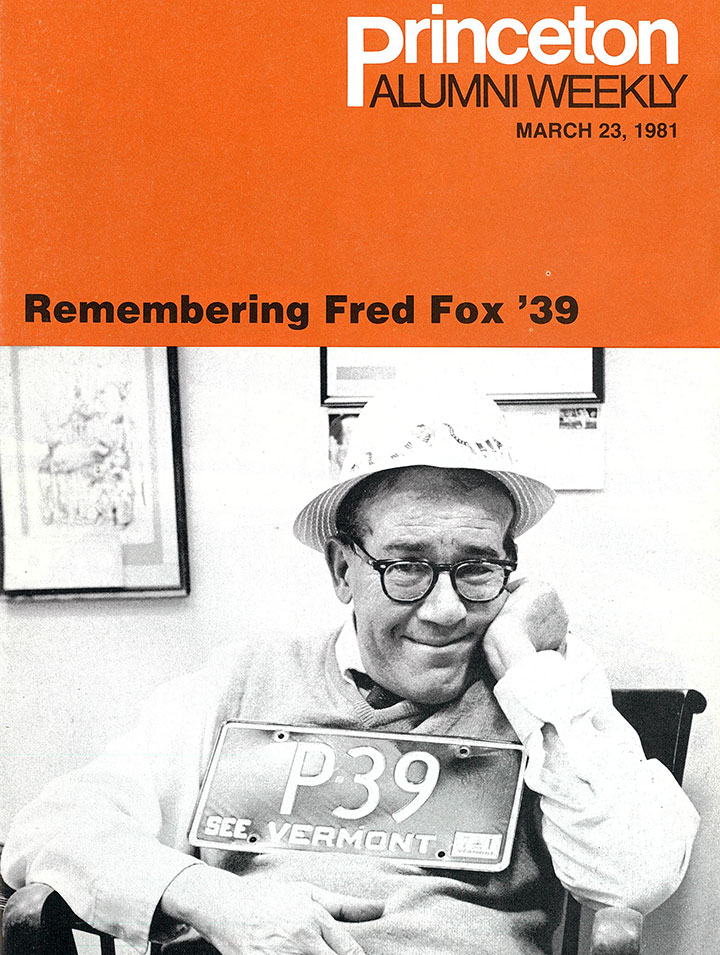

Bowen’s eulogy — published in its entirety in the March 23, 1981, issue of PAW, with the addition of two more full pages about Fred’s personal outlook and his World War II exploits — is not a philosophical danger to the four great addresses noted above, for the simple reason that it is a wonderful example instead of what a first-rate eulogy can be. It’s a love letter. Since virtually anyone and everyone who ever met Fred was in love with him, that wasn’t hard to pull off, but it’s a very well-executed love letter nonetheless, and deserves high praise on that basis alone. The president was clearly a huge Fred fan to begin with — he had created the Keeper of Princetoniana position that Fox occupied the last five years of his life — and so was able to convey a good deal of his spirit from the pulpit. The irony was that the perfect person to give the eulogy would have been Fox himself, who Bowen pointed out was everybody’s pastor. While he was indeed an ordained minister, that wasn’t the point of the comment; his care and kindnesses to those who might be confused or struggling were myriad, and a kind word was always leaving his desk for some Princetonian, either thanking or encouraging and very often containing some sort of tchotchke, in orange or black or stripes, or all three. In line with the many Princeton baptisms, marriages, and funerals he performed, the eulogy would have fit easily (he actually otherwise did the complete order of service for his own memorial, including a postlude by … the Tiger Band); meanwhile, as for being a rousing fundamentalist preacher, Bowen was an outstanding labor economist.

But Bowen succeeded wonderfully anyway by noting one crucial thing. In explaining that Fred was a man of real depth — which because of his cherubic demeanor, really did need to be explicitly said — Bowen brought up the river, which was Fox’s image of the great university as it recognized its traditions and looked toward the future. While the banks and the long-standing landmarks that line them are stable and recognizable from one generation to the next, the water is always new, and ever restless. When the river evolves and grows in strength and depth, it’s the fresh water that makes it happen. As encyclopedically knowledgeable as he was about Princeton’s past, it was with the students that Fred loved spending his time, because they had the new ideas, and they were the future of Princeton. His teaching of “Old Nassau” to each class at its freshman Honor System assembly was annually just as much of a love letter as Bowen’s eulogy. In the analysis of Fox’s view of tradition that follows the eulogy text in the PAW, Lisa Belkin ’82 notes that he warned her about the importance of the fresh-flowing water in the river — that when it became stagnant, the traditions suddenly became a huge burden instead of the common wisdom provided the University in important times of growth and creativity.

On Nov. 30, 1970, an editor at Random House who had just published her first novel, The Bluest Eye, spoke at the Wilson School for the new Afro-American Studies Program on “Afro-Americans in American Publishing.” This is the single instance I can find when Toni Morrison came to Fred Fox’s Princeton; there is certainly no indication they ever met. Her great address at the 250th anniversary was given a full 15 years after he died, after the advent of undergraduate colleges, molecular biology, a new president, and Cornel West *80 as director of African American studies. The waters changed quite a bit in those years. There is simply no way anyone paying attention would ever confuse the day-to-day foci or activities of Fox and Morrison. I would hazard a guess you wouldn’t confuse them chatting with students or walking down the street. Within our rich traditions, they seem to embody very different facets that each make Princeton unique as an institution of note and importance.

So it’s a significant lesson of history to note that Fox’s riverbank and waters on the one hand, and Morrison’s place of the idea, and idea of the place on the other, amount to a complex and unanimous opinion of how a place like Princeton (if there are many such things?) becomes, remains, and advances as a place like Princeton. And we might as well note, while we’re in the neighborhood, that the restless change they see as our legacy and our calling are prominent in the messages of Witherspoon, Wilson, and Stevenson as well. When viewed in that light, it makes a great deal of sense to mention Fox in that august company, and to note his legacies in the Princeton University Band, the Chapel ministries, Triangle Club, the Princetoniana Committee, and the University Archives alongside theirs in the wider world.

It is very hard, given their vibrancy, for those of us who knew and loved Fred Fox and Toni Morrison to really accept they’re no longer with us; based on Fred’s case, I suspect that will be true for a very long time at Princeton. Of course, considering all the above, we can also just realize that in any effective sense, they have simply gone over to the riverbank, the place of the idea, where they can serve as immediate guideposts to those of us out on the water, if we only have the wit to look up and see them.

No responses yet