Gino Bartali’s fame rests on his 1938 and 1948 wins in the Tour de France, which covered about 3,000 miles of sometimes-mountainous roads. Born into a poor family in a town outside Florence, Bartali had discovered a passion for bikes as a boy and became a leading sports figure in Italy.

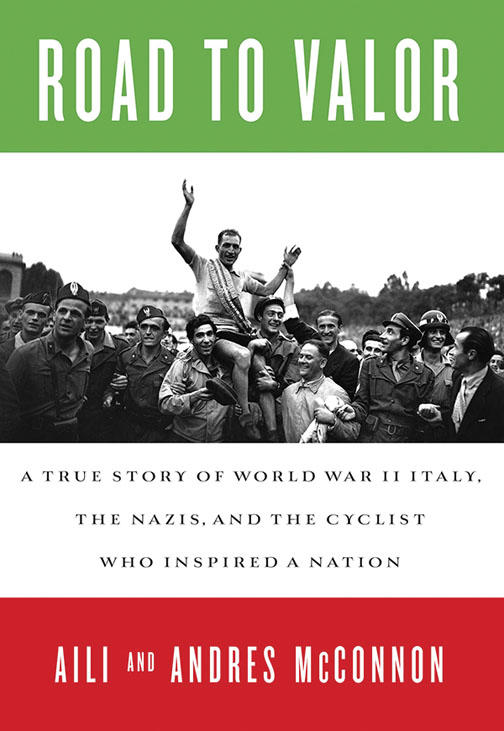

While Bartali’s sports prowess is well documented, much less is known about his wartime efforts to protect Jews in Italy during World War II. And that shadowy legacy sparked the sister-brother writing team of Aili ’02 and Andres ’05 McConnon to investigate the hard-riding, hard-living, deeply religious cycling superstar in a new book, Road to Valor: A True Story of World War II Italy, the Nazis, and the Cyclist Who Inspired a Nation (Crown Publishers).

Andres learned about Bartali while in Europe in 2002, watching the Tour de France. Bartali’s athletic achievement — maintaining his riding skills despite the war’s disruption — immediately fascinated him. The decade between Bartali’s wins still stands as the longest span between Tour victories. An Italian newspaper’s reference to Bartali’s work with the Resistance caught Aili’s attention. She recalls, “We realized there was a big sports story of him coming back against all odds, and then his secret work in World War II.”

Bartali’s rescue work began in the fall of 1943, at the request of his friend Cardinal Elia Dalla Costa, the Archbishop of Florence. A devout Catholic, Bartali accepted the plea. He had empathized with oppressed groups since he heard about the repression of the Italian Socialist Party, which his father supported, in the 1920s: A socialist who employed his father was murdered because of his politics.

During the war, Bartali’s training rides and work as an Italian Army messenger were a perfect cover — Bartali stored in his bike’s frame false documents that Jews used primarily to hide in Italy. He dodged military patrols to deliver the papers to monasteries, intermediaries, and other members of the Resistance, at one point enduring arrest and interrogation by the Italian secret police. Bartali also hid a Jewish family in an apartment he owned and then in a cellar until family members were liberated by the Allies in August 1944.

Aili, a journalist, and Andres, a researcher, spent three years researching and writing the book, chasing down people who knew Bartali in Europe, the United States, and Israel. They retraced Bartali’s path along the Tour’s mountain roads, read 80-year-old newspapers, and interviewed refugees, family members, race enthusiasts, and political leaders. In Tel Aviv, they met Giorgio Goldenberg, who was a boy when Bartali hid his family.

Bartali, who died in 2000 at the age of 85, captivated the McConnons as a man who acted on his beliefs, undeterred by opposing forces. “He was such a complex figure,” says Andres. He was an athlete who was a chain-smoker and liked to drink. Although he was religious, “he would hit somebody who got physically too close to him. He wasn’t self-censoring or a slick, packaged character. He was a star before the star apparatus as we know it now had been fully formed.”

0 Responses