Robert Francis Goheen '40 *48: Memories of a leader who mastered the art of listening

Traveling through New Jersey in the late 1960s with two classmates from Harvard, Stephen Goheen stopped back home in Princeton, where his father, the president of Princeton University, invited the trio out to lunch. Cambridge, even more than Princeton, was gripped by antiwar protests and unrest. Stephen, who later would perform alternative service as a conscientious objector, recalls that his father asked all manner of questions. Afterward it dawned on him that the elder Goheen had been “conducting research. He was trying to learn what we were thinking.”

That was Robert Francis Goheen, always listening.

After the man who led Princeton into the modern era died of heart failure March 31, many tributes touched upon Goheen’s ability to listen to other points of view and, as in the case of coeducation, to change his mind. “I have never known anyone with so little ego investment in winning an argument. Quite simply, he wanted to do right,” says Marvin Bressler, professor emeritus of sociology. “In a community in which many people confuse self-interest with principle, he led through the exercise of moral force.”

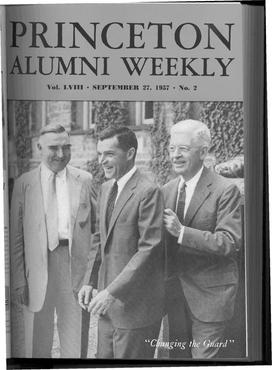

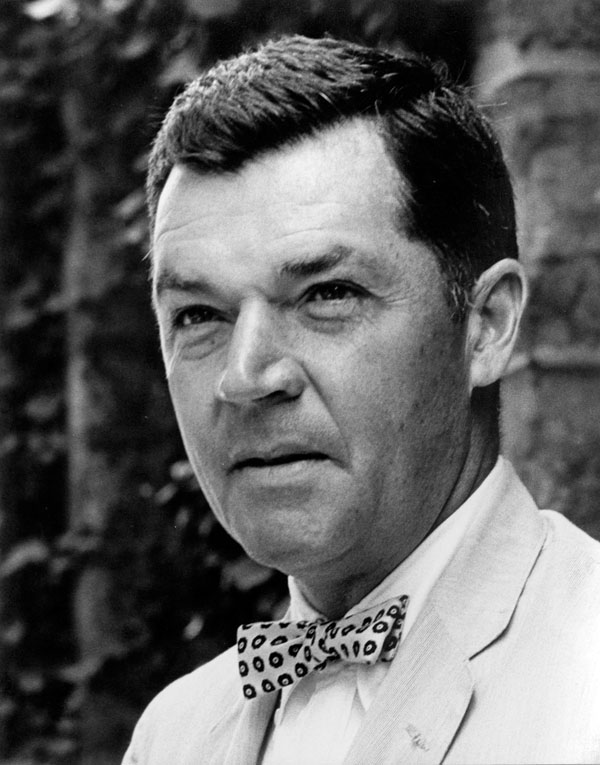

Taut, crew-cut, and bow-tied, Goheen, Princeton’s 16th president, could appear somber and aloof; even admirers admit he tended toward the formal. It was easy to picture Bob Goheen in his orange Class of ’40 blazer and boater, but not its beer jacket.

The onetime classics scholar who served as president for 15 years brought a keen eye for talent and a natural instinct for leadership to Nassau Hall. After expanding the faculty, facilities, and research capacity during what he called “the halcyon days” of his first decade, he made strategic moves over the next five years that made Princeton better and stronger, from creating the provost’s job and lining up economist William Bowen *58 as heir apparent to forcing the trustees’ hands on coeducation. He hired a young assistant professor from Harvard, Neil Rudenstine ’56, as dean of students when he realized that nobody in Nassau Hall really had a clue about the late-’60s generation. Earlier, he had brought in Carl A. Fields, the first black administrator in the Ivy League, to help overcome Princeton’s reputation as a place where minority students were not welcome. Then, he gave the faculty and even students a say in University governance. However imperious Goheen may have looked, he engineered these changes not by dictate, but consensus.

“He was a genuinely kind and thoughtful person,” says Charles Fuqua ’57, whom Goheen and his wife, Margaret, hired to babysit their six children. Fuqua majored in classics after taking a class from Goheen and, like his mentor, wrote his dissertation on Sophocles. He served in the Navy after graduation and was spending the summer of 1960 back in Princeton when he encountered Goheen on the street. The president promptly invited him to move into Prospect for the summer, while the Goheen family was summering on Cape Cod. “That I did, and it was a most pleasant change of quarters,” remembers Fuqua, a Williams College professor emeritus of classics.

To Venkatarama Krishnan *59, Goheen was a welcoming host who invited him and other Indian students to his home on Orchard Street; the MIT professor emeritus still counts his Princeton diploma, “signed by Robert Francis Goheen ... [as] my prized possession.” Journalist Don Oberdorfer ’52 recalls Goheen as an “open and approachable faculty member” who Oberdorfer felt would “knock off the cobwebs and lead the University into a new era” as president.

Silvia S. Bennet, widow of John R. Bennet ’30, remembers the dashing figure that Goheen cut at Reunions in 1960. She paints this scene of the P-rade: “Through ’79 Arch with Woodrow Wilson’s flag flying overhead swung the band; then, there, at the top of the steps in full 20th reunion uniform, was the young president! Unforgettable.”

When a girlfriend of Malcolm J. Odell ’62 painted a landscape on the bare, cinderblock wall of his dorm in the New New Quad, the University immediately served notice that it would have to be repainted at Odell’s expense. He drafted a formal apology —- in Latin, no less — and presented it to Goheen while the president was reading a newspaper in the Student Center. Odell tells the rest of the story: “Peering up over his half-glasses, [Goheen] smiled and inquired, ‘And what is it, pray tell, that you are apologizing for?’ I briefly outlined the situation, the art, and my request that the mural be allowed to stay. ‘I’ll look into it,’ he said with a wry smile, returning to his paper. That evening, returning to my room I was intercepted by the custodian. ‘The mural stays!’ he said with delight. ‘The president appeared here this afternoon, looked it over, and gave the order to Buildings and Grounds that the mural stay. We won!’”

In 1965, freshman class president Paul G. Sittenfeld ’69 and fellow officers were summoned to Nassau Hall to settle an impasse over Sittenfeld’s plan to sponsor a Princeton entry in an intercollegiate elephant race in California. Goheen negotiated the compromise: The Class of ’69 could sponsor a turtle in an intercollegiate race in Maryland.

Tougher challenges lay directly ahead. At a rally outside Nassau Hall on May 2, 1968, students and faculty pressed demands that the University oust the Institute for Defense Analyses (a nonprofit corporation that did research for the Pentagon), divest stock from companies doing business with South Africa, and scrap the last vestiges of in loco parentis rules governing student life. Peter J. Kaminsky ’69, who was both the Undergraduate Assembly president and a leader of Students for a Democratic Society, penned a fond tribute to Goheen in The Daily Princetonian the day after Goheen’s death. The president was never inquisitorial or “too disapproving, even when politics divided us,” he wrote.

Goheen was on the scene at virtually every major event during the period of campus unrest. Prince reporter and later chairman Richard K. Rein ’69 heard him mutter, “This isn’t Princeton,” as local police hauled away 30 students who had blockaded the IDA’s doors in October 1967. Goheen later explained that he meant it literally — leased Von Neumann Hall was under the IDA’s control. Indeed, the University never called the police onto campus, even when the Association of Black Collegians occupied New South, an administration building, for 11 hours in March 1969. The black students left of their own accord, and ABC leaders later got an audience with the trustees’ financial committee to press their case for divestiture. Lee Neuwirth ’55 *59, a mathematician who was deputy director of the IDA’s Prince-ton operation, says, “In the bull’s-eye during that tumultuous period in the University’s history, President Goheen walked a tightrope with dignity, grace, and great skill.” Health-care lawyer Brent L. Henry ’69, an ABC member who became the first graduating senior elected to the board, says that when he observed Goheen running trustees’ meetings, it was clear “he was the agent of change in that room.”

Goheen’s change of heart on coeducation — erstwhile Prince reporter Robert K. Durkee ’69, now Princeton’s vice president and secretary, broke the scoop during reading period in May 1967 — estranged some alumni. An alumni group opposed to coeducation sought unsuccessfully to get Herb W. Hobler ’44, owner of WHWH radio in Princeton, elected to the board. Today, Hobler thinks Nassau Hall could have handled alumni critics better back then, but he came to support coeducation and says, “I think Bob did a magnificent job. He had vision. He handled the things going on ... better than most college presidents.”

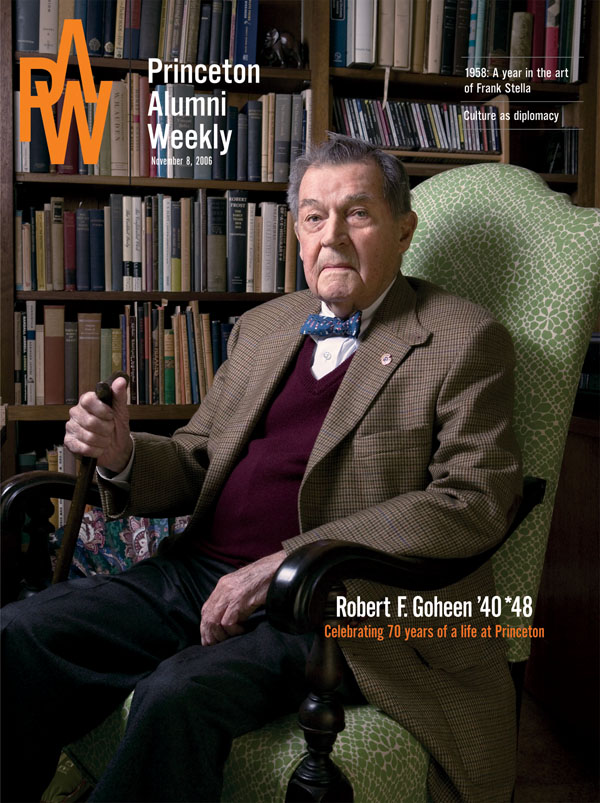

President Jimmy Carter’s appointment of Goheen as ambassador to India in 1977, five years after he retired as University president, was a grace note to a career of service. Upon returning from New Delhi, he became a senior scholar at the Woodrow Wilson School; later he helped create Princeton Future, which sought to preserve the downtown’s character. To the end, he embraced progress and adaptability: About 18 months ago, Goheen asked his class secretary, William N. Kelley, for a list of class e-mail addresses (20 of the 125 survivors, including Goheen, had them). At recent Reunions, when marshals complained that the Class of 1940 was slowing down the P-rade, the former president would exhort classmates to use canes, as he did. “He said, ‘This is no time to be proud. This is a very practical item, and I couldn’t get along without it,’” says Kelley. (Eventually marshals pressed the entire class to ride in golf carts.)

John V. Fleming *63, the Chaucer scholar and faculty lion whom Goheen recruited to be master of Wilson College, says, “Bob’s role was never to impose his private views on reluctant colleagues, but to lead his colleagues to a fuller and shared vision of the particular institutional genius of Princeton. That was no mean accomplishment: to demonstrate that sometimes dramatic change was not a departure from, but rather the fulfillment of, a traditional mission of liberal and humane education.” Fleming, now emeritus, adds that Goheen’s “profound sense of public service, of duty, of citizenship, and eventually of education itself, was derived in large measure from the traditions of Christian humanism in which most of our great educational institutions, conspicuously including Princeton, were themselves founded. This source of inspiration was for President Goheen rich, generous, liberating. There was nothing narrow in the man, nothing constricted or dogmatic.”

Goheen was the kind of person “with whom one could sit comfortably in silence,” recalls Marsha Levy-Warren ’73, an author and psychoanalyst who was the first woman to win the Pyne Honor Prize and be elected an alumni trustee. An exchange student in India before entering Princeton, she and Goheen sometimes would talk about the food, the music, the smells and colors of that place. They’d remember something together, she says, and then sit without speaking.

“He was a quiet and calming leader,” Levy-Warren says. “People don’t realize how difficult it is to listen — and he did it naturally.”

That was Robert Francis Goheen.

2 Responses

Larry Campbell ’70

17 Years AgoPsychological judo

From reading “Memories of a leader who mastered the art of listening” (feature, May 14), I can see my most memorable experience of President Robert Goheen ’40 *48 was right in character.

In early 1970 I founded a town/gown group called Princeton Energy Action. True to the tenor of the times, we developed three “demands” that I took directly to the ever-accessible President Goheen. We “demanded”: 1. Close and allow us to reclaim a road that was eroding into Carnegie Lake; 2. Designate a wild, natural area an area near faculty housing that was slated to be cleared for sports fields; and 3. Form a committee to plan a multidisciplinary ecology program.

In fact he did listen, and then, disarmingly, agreed immediately. For me this was psychological judo. With nothing to push against, I looked back at myself in chagrin at my unnecessarily demanding attitude. That and his measured response to the sit-ins at the Institute for Defense Analyses, which I also participated in, won my everlasting admiration.

President Goheen was an extraordinary soul in the right place at the right time.

Bernard S. Adams ’50

10 Years AgoMore Goheen tales

In the fall of 1952, I joined the Princeton admission staff under Bill Edwards ’36. Joe Bolster ’52 and I were the only staffers. A few years later, Bob Goheen invited me to spend a couple of hours daily helping him with the Woodrow Wilson Fellowship Program — from 4 until 6 p.m., five days a week. And thereby hangs my tale.

Around that time, I was invited to move to the University of Pittsburgh as that institution’s first director of admission. I asked Bob for his advice and he encouraged me to accept the offer — in part because it would allow me to finish a Ph.D. in English, which I had begun six years earlier at Yale. Then came Bob’s further response: “If I’m not promoted pretty soon (from assistant professor of classics), I’m going to start looking, too.” About a year later, Bob was “promoted” — to president!

I’ve always been grateful to Bob — not only for his advice, but for the example he set. I did finish the doctorate and went on to be president of two small colleges, one private and one public.

Like all of you at Princeton, I’ll miss him.