The Senior Thesis at 100: Back to the Future

AS PRINCETON MARKS THE 100TH ANNIVERSARY of the senior thesis, what anchors one of the University’s most revered — and arguably, most daunting — traditions is the belief that each and every student can surprise themselves if given the chance. Patricia Fernández-Kelly, who has taught sociology at the University since 1997, is one member of this thought camp. Having advised upward of 80 theses, one of Princeton’s most prolific thesis advisers claims “that a senior thesis does fulfill an extraordinary purpose.” It allows students, she says, “to discover things that they never thought that they’d discover.”

Discovery comes in many forms. Most of the time, it is a personal affair, a point of growth. On the rare occasion, it might make headlines. In early 2023, Edward Tian ’23 was in the news after launching an AI-detecting application derived from his thesis-in-progress. GPTZero, a tool that discerns whether a text was produced by ChatGPT based on its “burstiness,” or the degree to which its language and sentence structures are unpredictable to machines, was viewed by a quarter of a million people within its first 20 days on the internet, according to Tian.

Tian, a B.S.E. graduate of Princeton’s computer science department, didn’t have to write a thesis. (The thesis is mandatory for all seniors except those pursuing B.S.E. degrees in computer science, mechanical and aerospace engineering, and operations research and financial engineering.) But his interest in writing and journalism pushed him to produce something public facing. “There’s a lot of worlds colliding where the work needs to be done,” says Tian, who had spent a year between his sophomore and junior years with the BBC using data tools to investigate misinformation. When he told his former professor John McPhee ’53 — whose sentences Tian fed into GPTZero to demonstrate how the tool worked — about what he had accomplished, McPhee’s exhortation was surely and unsurprisingly “bursty,” Tian recalls: “He said, ‘Go dazzle the cyberzone.’”

It’s exactly the kind of thing any undergraduate would want to hear as they launch themselves into the rest of their lives. Because the Princeton senior thesis is no mean feat — nor is it a static event. Eleven years ago, PAW published a retrospective of the tradition with testimonies from a range of alumni. But with the advent of AI technologies and the coronavirus pandemic, the decade since has already pushed the thesis beyond what it has historically been. And what it has been is a blueprint for a young person coming of age in their intellectual and creative journey; an example of the extraordinary things Princeton students can do, given the right support; and an exercise requiring focus, persistence, and a dash of good humor, virtues that feel more timeless now that a hundred years have passed.

A NEW TRADITION

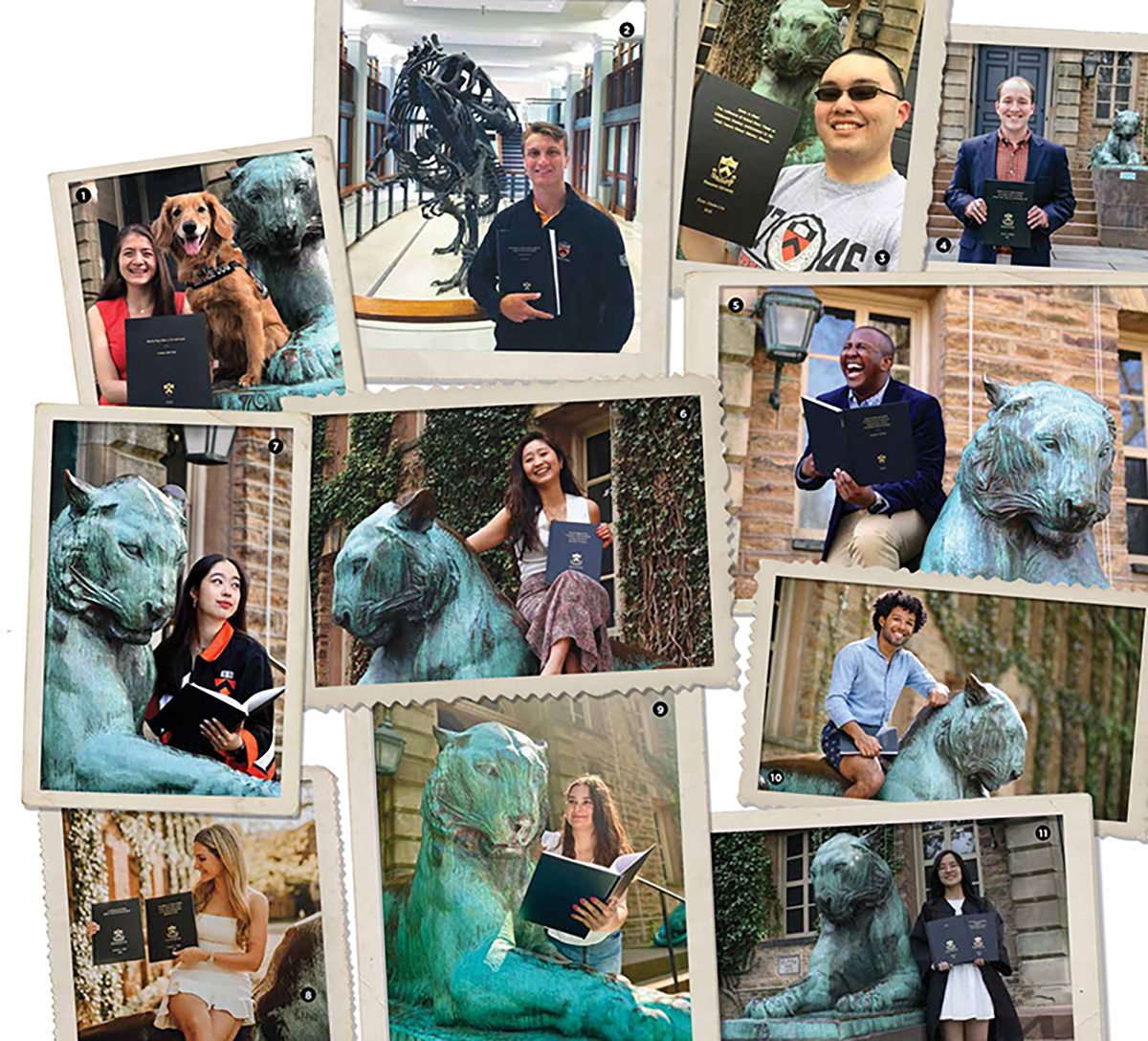

In recent years, students have started taking photographs with their senior thesis in front of Nassau Hall. These alumni shared their photos with PAW.

1. Camden Olson ’19, “Service Dog Tales: A Tri-fold Study Investigating Diabetic Alert Dog Accuracy, the Use of Animal-Assisted Therapy to Address Executive Functioning Skills, and the Function of Calming Signals in Service Dog Puppies”;

2. Evan Saitta ’14, “Paleobiology of North American stegosaurs: Evidence for sexual dimorphism”;

3. Zhan Okuda-Lim ’15, “Early to Rise? The Influence of School Start Times on Adolescent Student Achievement in the Clark County School District, Nevada”;

4. Connor Pfeiffer ’18, “Britain and the ‘German Revolution’: The European System and British Foreign Policy During the Franco-Prussian War”;

5. Brandon McGhee ’18, “The Blacker the Berry: The Black Church, Linked Fate, Marginalization, and the Electability of Black Candidates”;

6. Jimin Kang ’21, “Tales from Indigenous Brazil: A Translation of Daniel Munduruku’s Chronicles of São Paulo & The Lessons I’ve Learned from the Portuguese”;

7. Victoria Pan ’21, “Are Lockdown Orders Driving Job Loss? Characterizing Labor Market Weakness During the COVID-19 Recession”;

8. Daniella Cohen ’22, “Inter-Subject Correlation Analysis Reveals Distinct Brain Network Configurations for Naturalistic Educational Stimuli”;

9. Juliana DaSilva ’23, “Investigating the role of Hh signaling during embryonic germ cell migration in Drosophila melanogaster”;

10. Devin Kilpatrick ’19, “Sojourners from Central America: A Study of Contemporary Migrants & Migration from Guatemala to the United States”;

11. Alice Xu ’20, “Pretty, and The Promises and Compromises of Happiness: Idealism, Realism, and Choice in Jane Austen’s Novels.”

THE IDEA FOR THE SENIOR THESIS was born in the immediate aftermath of World War I when Luther Pfahler Eisenhart, an effervescent math professor who quickly rose through the ranks to become Princeton’s dean of the faculty, proposed slashing the traditional five courses in an undergraduate curriculum to four. The resultant free time would go toward independent study of the student’s choosing, a policy that, at most other schools, had only ever been reserved for those seeking honors. (To this day, the pattern holds: Though some seniors at other U.S. universities write theses, the task is optional for those hoping to graduate with extra laurels.)

With the pedagogical magnanimity that Eisenhart was known for, he fervently believed that grades achieved in the first two years of one’s time at Princeton “did not constitute a reliable test of a student’s ability to qualify for honors,” writes Alexander Leitch 1924 in A Princeton Companion. Rather, only when given the chance to “function freely” on their own would students prove their academic mettle.

It is this sense of possibility that renders the thesis a subject of enduring fascination for generations of alumni. Testimonies of the thesis-writing experience abound, both online and elsewhere: in the archives of this very magazine; the dozens of reflections collected in Nancy Weiss Malkiel’s 2007 anthology The Thesis: Quintessentially Princeton; on bookcases across campus but most notably in the Mudd Manuscript Library, where thousands of theses — especially those submitted prior to the digitization of theses in 2013 — are kept.

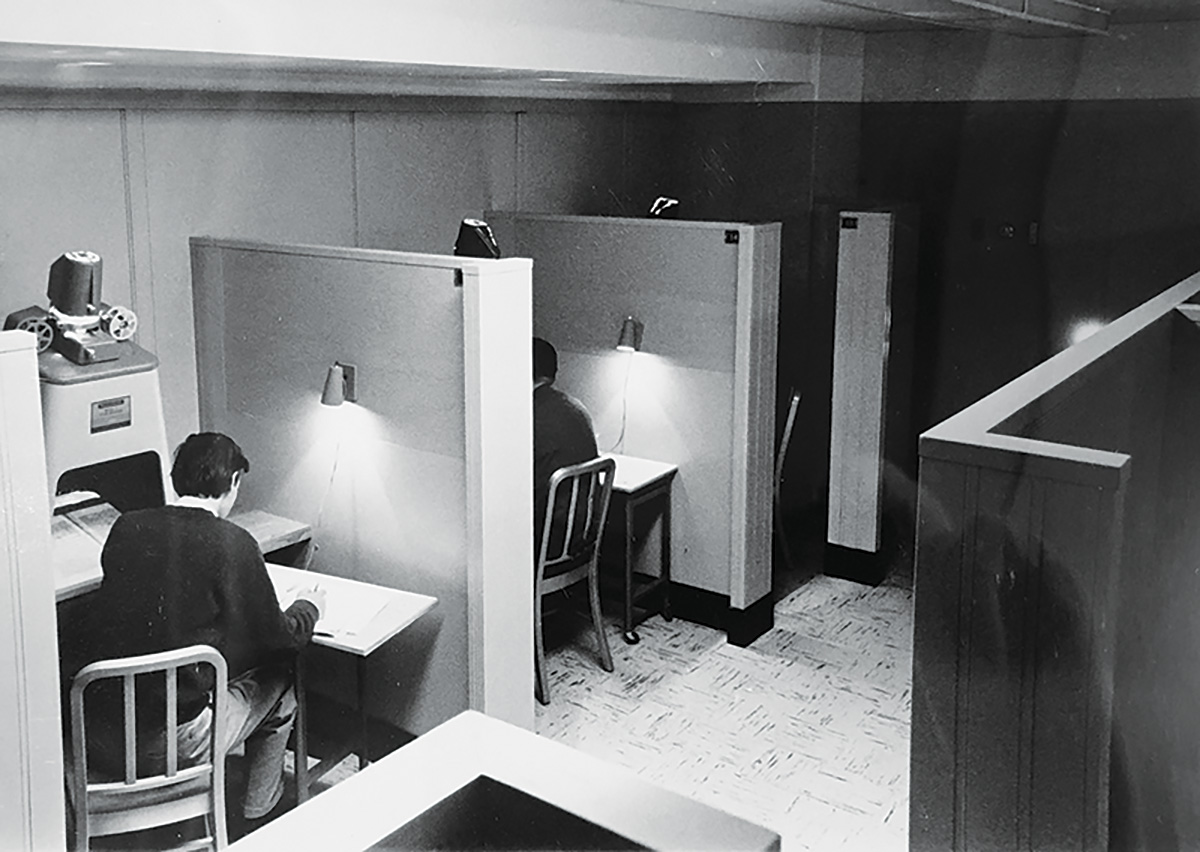

Then there are the senior theses about the senior thesis. Most readers of this article will open the work of Melissa Gracey DeMontrond ’00 to find themselves in the dedication. “First and foremost,” it begins, “I would like to dedicate this thesis to every individual who has ever gone through the torturous and merciless process of writing a senior thesis at Princeton University. I know your pain.” A handful might even find themselves in DeMontrond’s photographs of seniors burrowed away in Firestone’s metal carrels, metallic 3-by-8 boxes that thesis writers used as a kind of office, or in the stories of “cubby hole parties” that took place among these carrels, which Kelly Ehrhart ’97 describes in her own thesis about the thesis. (The carrels were removed in 2012, except for three that have been preserved in Firestone Library. By the time I arrived at Princeton, one couldn’t hide behind a sliding door, but they could overhear other people’s conversations on the other side of the open-air carrels.)

Both DeMontrond and Ehrhart were anthropology majors fascinated by the thesis as a rite of passage. How a student might enter Princeton as a child but emerge, after being shepherded through a series of challenges within a community of like-minded peers, a worldly adult. “The thesis process has altered my state in the world and made me aware of what is to come in the way of responsibility and behavior,” Ehrhart writes in her conclusion. “However much it is complained about and however despised it may be, the thesis is one of the most integral events that I will ever endure.”

It’s true: The thesis calls upon young people for an ingenuity that emerges from no source but themselves. Often, the results become astounding contributions to society. The list and lore of “famous theses” are well-known: John C. Bogle ’51 created Vanguard, one of the world’s largest providers of mutual funds, from his thesis; Wendy Kopp ’89, Teach for America, which has impacted more than 5 million students across the United States; Jonathan Safran Foer ’99, his first novel, Everything Is Illuminated, which was adapted into a 2005 film and launched his writing career.

There are dozens of other examples besides. One of the lesser known is how Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi ’00 — whose 2023 biopic Nyad was nominated for two Oscars — launched her filmmaking career with a documentary she made in Kosovo to fulfill part of her thesis requirement in comparative literature.

Co-directed with Hugo Berkeley ’99, A Normal Life, which follows a group of five remarkable young people building their lives under the shadow of war, won best documentary at the Tribeca Film Festival in 2003. Fifteen years later, Vasarhelyi and her partner, Jimmy Chin, won an Oscar for their nail-biting documentary Free Solo, which follows professional climber Alex Honnold as he climbs a 3,000-foot-tall summit in California’s Yosemite Valley without any harnesses or ropes.

Vasarhelyi decided to major in comparative literature because of her fascination with “representing the unrepresentable,” she tells PAW. As the child of parents who emigrated from their respective countries due to religious and political persecution, she wanted to explore the tensions between people’s identities and their political contexts. Her project thus became not only her version of film school, but the culmination of four years spent pondering a question that she had really been asking all her life. “Finding the space academically to nurture this curiosity of mine was really meaningful,” she shares. “It defined my whole career. I’ve made films ever since.”

Importantly, most of Princeton’s star-studded theses are works-in-progress that later grow to become much more.

Vasarhelyi edited A Normal Life from her parents’ basement for another two years after graduation. Jordan Salama ’19, whose thesis was the first to become a University Pre-read for incoming freshmen, spent the pandemic rewriting what would become Every Day the River Changes, his nonfiction debut about the communities that live along Colombia’s Magdalena River. Ask him for the full story and you’ll learn that the real work took even longer than that. Salama, a Spanish and Portuguese concentrator, was first inspired to write about the river while pursuing an internship in Colombia after his freshman year. It took multiple returns and the encouragement of his adviser, Christina Lee *99, to create the final submission, which he presented at a fateful journalism colloquium where he was connected to an agent who sent a PDF of Salama’s thesis to some of the nation’s largest publishers.

But trace the story further back, and much like Vasarhelyi’s case, you’ll find that Salama’s story began long, long before he set foot in Old Nassau. Salama’s family is Argentine on his father’s side, and his great-grandfather — the main subject of his most recent book, Stranger in the Desert (2024) — emigrated there from Syria to work as a traveling salesman. Salama only became fluent in Spanish when he came to Princeton, where his experience was one of “opening [his] eyes to Latin America,” he says.

These days, Salama looks back on his Princeton trajectory not only with wonder, but a great deal of humility. “Nobody’s an expert in anything when you’re a senior in college,” he says. And so, throughout the many conversations he shared with strangers and the funny encounters he had — my personal favorite: Salama unexpectedly hearing his rendition of Oasis’ “Wonderwall” played on the sound system in a bar in Puerto Boyacá — he “leaned into it.”

At the end of the day, perhaps that’s what a thesis is: an impressive feat, yes, but also little more than an honest testament to who a young person is and a proof-of-concept for how they mean to go on.

THOUGH ALL THESE ARE PIONEERING IN THEIR own ways, some are more pioneering than others. Given the immense range of senior theses produced each year, it’s difficult for any single thesis to jump out — or earn a legendary status — as soon as it’s written. But ask any Princeton math major from the past decade about the most fabled thesis they know, and you’ll surely hear about Mason Soun ’15. Inspired by the work of math writer Danica McKellar, Soun wanted a way to explore the trials and tribulations of studying math while championing what inspires people, as he writes in his introduction, “to fall in love with this subject in the first place.”

Combining his passions for math education and creative writing, he went on to produce something exceptional: a thesis composed of comical short stories — featuring fictionalized versions of Justin Bieber, Kim Kardashian, and Kanye West — whose plots revolve around linear algebra and the experience of working with numbers. The first story, “To Beliebe,” follows an earnest and somewhat pitiable version of Bieber as he attempts to become a knife-seller with a company called Vector Marketing.

In one archetypal scene, the Canadian superstar attempts to sell knives — which can be lengthened or fastened together, like vectors — to an old man surnamed Gomez, whose adamant refusal prompts the singer to respond, winking: “Never say never.”

“It was very much an outlier in the math department,” recalls his adviser Jennifer Johnson, who says she enjoyed working with Soun. “He was very serious about the idea of looking for ways to make math less frightening and to share his enthusiasm for mathematics with young students.” (Though it was an “interesting experiment,” she adds, she doesn’t think she “would want to try anything like this again.”)

Sometimes, it is not will but circumstance that calls for seniors to get inventive. Arguably, some of the most exceptional seniors in recent years — and I relinquish any bias — belong to the Class of 2021, who had to evacuate campus just as they were submitting proposals for their senior theses.

Chris Gliwa ’21, a civil and environmental engineering graduate from East Rutherford, New Jersey, had anticipated research at a global scale. Instead, he found himself walking around his neighborhood amid a pandemic that had unexpectedly brought him home.

“It was during these walks that I became more perceptive of the industrial character of my neighborhood,” Gliwa says. In addition to exploring a nearby industrial complex that had once housed a bleachery during the American Civil War, he had socially distanced conversations with elderly neighbors who would share stories about the health problems that had proliferated in the area since the industrial boom in the 1960s. “They said that mysterious illnesses were common, but the companies and local leaders always assured them that there was nothing to worry about.”

Upon scouring a 1980s site assessment and decades-old news articles, Gliwa was compelled by a key culprit: benzene, a highly carcinogenic chemical used in industrial processes. With this discovery, a thesis was born. In the months that followed, Gliwa estimated airborne benzene concentrations using historical site data, then used wind records to build a model demonstrating how benzene would travel into the areas where his neighbors have lived for generations. Though his intention was “not to find conclusive evidence of wrongdoing,” Gliwa explains, his study’s confirmation of environmental pollution in East Rutherford was enough to vindicate his neighbors, whose response made Gliwa “very emotional.”

“They are like family to me,” he reflects, three years on. “People from my community rarely go to schools like Princeton, so to exercise my education and research skills in this way was truly a once-in-a-generation opportunity.”

Though Gliwa chose not to publish his thesis due to the possibility of legal concerns, he continues to build upon the skills that made his project possible with a long view toward tangible policy change. These days, he is fulfilling his third year as part of the University’s Scholars in the Nation’s Service Initiative (SINSI). His first rotation was with a team working on climate and environmental issues at the White House.

DESPITE ITS REPUTATIONAL CHARGE, the senior thesis isn’t immune to change. (Nor is it immune to critique: In the 1990s, a debate on its potential abolition made it to The New York Times.) As each generation of Princetonians paints new strokes on the hallowed portrait of this timeless tradition, the University has had to reframe the assignment. Creative theses — in which seniors produce novels, films, plays, and dance performances, among other things — are a fantastic case in point. Since Edward T. Cone ’39 submitted the first creative thesis in the form of a self-composed string quartet, hundreds of Princetonians have followed suit, giving rise to “hybrid” theses in which students (in certain majors such as English and comparative literature) fulfill their thesis requirement with a creative project supplemented by a critical essay. Online records of creative writing submissions since 1995 document a rising trend: Since 2013, there have been consistently more than 20 seniors each year submitting creative theses, while the preceding class years are patchier, with anywhere between one and 18 theses on record.

In the early 1950s, the University granted Robert V. Keeley ’51 *71 permission to become the first student to submit a novel as a senior thesis. Less than a decade later, there were six seniors writing novels to graduate.

Looking forward to the next 100 years, what might we expect of the senior thesis? Will it continue in the same way it has, or become an entirely different affair altogether? Perhaps the most salient question hovering over the thesis’s future concerns the rise of new technologies, including the widespread availability of digital data and AI.

“I have the impression that students are increasingly looking at small topics as opposed to trying to engage large ideas,” says Fernández-Kelly, referring to the use of large databases for research data instead of the slow, sometimes painstaking work of studying systemic issues on the ground. “But that isn’t a problem with the senior thesis, but a problem with our culture.”

In response to the popularity of generative AI tools, deans Jill Dolan, Kate Stanton, and Cecily Swanson (the latter two co-chairs of the University’s working group on such technologies) issued a campuswide memo in August stating that policy on using AI in assignments would be up to the discretion of teaching staff. “We believe that the powers and risks of generative AI should only deepen the University’s commitment to a liberal arts education and the insistence on critical thinking it provides,” they wrote.

Should faculty permit, the future Tian envisions might just as well become reality soon: one in which thesis writing is a combination of AI-assisted and human-derived work. But this isn’t something that keeps the GPTZero founder up at night.

“Standards of student writing are derived from best practices in the real world,” he explains. “This is an exciting opportunity in the reverse: How students are writing theses or using AI tools responsibly will help define how people are using a combination of these technologies after they graduate.”

Not long from now, Jeremiah Giordani ’25 — who for one PAW article described himself as “one of the biggest ChatGPT users at Princeton” — will be brainstorming thesis ideas. The computer science concentrator, who laments the view that generative AI is for lazy students seeking easy ways out, considers the tool on par with calculators or spellcheck functions: time-saving technologies that give people the cognitive freedom to focus on creative tasks.

“These technologies are here,” he says. “They’re very useful, and to become as skilled as possible, it’s necessary to learn how to use these tools as well as you can.” Though Giordani is not yet sure what he’ll research, he plans to find an adviser who has a liberal, and even encouraging, approach to using ChatGPT.

Regardless of who (or what) will do the writing, that’s one thing computers will never change: the very human relationships students build with their advisers. True, some pairings may hardly ever meet, and some seniors have admitted to avoiding their advisers altogether. But when a senior and their adviser click, history shows that the learning and guidance often go both ways.

Malkiel’s 2007 collection The Thesis, which gathers interviews with Class of 2006 seniors and their advisers on the thesis research process, includes the story of ORFE concentrator Lindsey (Cant) Azzaretti ’06, who, for her thesis, came up with the idea of applying modeling techniques to the optimization of human blood storage. Her adviser, Warren B. Powell ’77 — who had advised upward of 200 undergraduate theses before his retirement in 2020 — was inspired. “The problem is now featured in a book I am writing on approximate dynamic programming, and I have already used it in a tutorial I have given on the topic,” his section in the anthology reads. “All this for a problem that would never have occurred to me.”

“This is an exciting opportunity in the reverse: How students are writing theses or using AI tools responsibly will help define how people are using a combination of these technologies after they graduate.”

— Edward Tian ’23

on using AI in students’ work, especially theses

Lee, Salama’s thesis adviser, says she believes the advising experience has influenced her own approaches to scholarship. Published in 2021, her most recent monograph — which explores the life of saints and their believers in the Spanish Philippines — features a foreword in which Lee explains how her identity as a Korean Argentinian compels her to study the intersection of Asian and Hispanic worlds. “I realized that you can write a good, strong piece of academic work that has personal resonance,” says Lee, whose work with Salama and other students has often concerned the incorporation of the first-person voice. “I’m not sure I would’ve done this if I hadn’t directed a thesis,” she adds.

To summarize the sheer diversity of theses from the past century — and to predict what they will look like in the next — is to partake in the same quixotic fervor of Eisenhart’s original vision. But for each student who has cried in a carrel is one who has laid a cornerstone for an illustrious career, or, at the most basic level, realized that they had it in themselves to do something incredible, and in their early 20s, no less. How big the world seems after such an accomplishment, and the rest of life so doable — or perhaps it is simply the comic relief of shared suffering that buoys us along. That much hasn’t changed; when members of the Class of 1925 designed their Reunions beer jacket, they included a tiger being crushed under four massive tomes. And what about the Class of 1924, the last batch to escape the mandatory thesis?

Their beer jacket featured a horseshoe. They couldn’t believe their luck. But whether that was a prescient choice, I’ll leave to the reader to decide.

Jimin Kang ’21 is a freelance writer and recent Sachs scholar based in Oxford, England.

12 Responses

James G. Russell ’76

1 Year AgoA Plus for Profs, Too

Toward the end of Nobel laureate Danny Kahneman’s excellent book Thinking Fast and Slow he wrote, “One of the privileges of teaching at Princeton is the opportunity to guide bright undergraduates through a research thesis,” followed by almost two pages about the process and conclusions of one of his favorites among the theses he supervised. It is good to see that the thesis requirement is a plus for the right kind of professor. Long may it continue.

Rocky Semmes ’79

1 Year AgoCompliments for PAW’s Coverage and Cover Art

The peerless and purposeful Princeton Alumni Weekly proves constantly and consistently captivating, capturing masterful content of mesmerizing merit, issue after incredible issue. One is hard-pressed to find better reading, in both content and style, in any other periodical of any kind.

The icing on the cake then (so to speak), is the accompanying artwork, which included the ingenious PAW-commissioned confectionary cover of May 2024 and also the brilliant eye-relieving illustrations complementing the June 2024 text of “Aaron Burr 1772’s Forgotten Family” by Kushananva Choudhury '00.

The PAW might — just possibly — outdo the inimitable one-of-a-kind P-rade as the most richly rewarding residual of matriculation at the "best damn place of all"!

Richard H. Eisenhart Jr. ’66, Douglas M. Eisenhart ’72

1 Year AgoThe Value of the Thesis, Realized in Retrospect

We are grateful to Jimin Kang ’21 for her thorough research and look back at the centennial of the Princeton thesis in “The Senior Thesis at 100: Back to the Future” (May issue). Kang’s article properly credits Dean Luther Eisenhart as progenitor of Princeton’s independent study and the senior thesis from his time as dean of the faculty in the early 1920s.

Like many other readers of the piece, the pain of this ordeal and ultimately sense of accomplishment came back to us as we relived our own thesis sagas. What gives us additional pride, though, is how this capstone project of the Princeton undergraduate academic program has not only survived but thrived for a century, for reasons not only relayed in Kang’s piece but that Eisenhart himself understood as stated in his 1945 book, The Educational Process: “Many students have said that it was their first experience in college in feeling that what they were doing was really their own. Also graduates have testified that their work on a senior thesis was excellent training for investigations they made later, as part of their business or professional life, or as interesting avocation.”

The true value of the thesis experience, it seems, is most often realized in retrospect. We say thank you to Jimin Kang for her fine article, and we also say thank you to Dean Eisenhart for this enduring contribution to Princeton.

Editor’s note: The writers, brothers, are great nephews of Dean Luther Eisenhart.

Susan P. Chizeck *75

1 Year AgoRemembering the Carrels

Seeing a picture of the carrels brought back so many memories. They were a godsend when you had to use many heavy books for your research and it was so much easier to store them there. It was a dedicated study space with few distractions, and you could keep your research all organized and safe. Of course, after a while people on the same corridor became friends and took study breaks together, then shut ourselves back in to work. What a mistake to get rid of them. They were wonderful for me, and I wrote a great thesis, on some obscure artist, never to be seen again by humans. But it taught me so much.

Michael Richman ’85

1 Year AgoThesis Memories and a Missed Opportunity

I'm sure others will also point out that the photo on page 36 shows a machine for microfilm, not microfiche (as indicated by the photo caption). Although I will acknowledge that when working on my thesis, I did look at some materials on a microfiche machine in Firestone. (Editor’s note: PAW has updated the caption above.)

To the extent I can remember it, like those quoted in the article, I recall working on my senior thesis as a history major as a rewarding experience (at least once it came to an end, following a short extension provided by the college after a problem at the computer center the day before they were due). What I wonder about, though, is what might have been if I had pursued a different topic.

At the beginning of senior year, I went to Professor James McPherson, who had not yet published Battle Cry of Freedom, about a research idea I had based on a project I had worked on the previous summer in the Firestone rare book room, organizing papers of a family that included a Civil War admiral — possibly the only member of the Virginia Lee family to have served on the Union side. But I had not taken any courses in Civil War-era history at Princeton, so he discouraged me from pursuing it.

If I had planned differently, I might have been able to engage with a topic that allowed for more in-depth work directly with conveniently located primary sources, possibly one of the first to work with those sources in any detail. But I was able to complete the work, got a decent grade and graduated, which is what mattered at that point in time.

Meanwhile, all the extra copies I made of my senior thesis for various family members have been coming back to me after the family members have passed on, so I now have several reminders of how I spent my senior year.

Patrick Bernuth ’62

1 Year AgoOn the Thesis, and Later Lessons

I skated through Princeton. The ice was always thin, and it wasn’t until the senior thesis that it broke and I tumbled through. My grade — a six — meant I would not graduate with the rest of my class. Failure writ large. Princeton was kind to me and in the following year gave me another chance. The next year I got the degree: box checked and off to a life in business and publishing.

I was an ordinary undergraduate for those days — entitled white boy from the suburbs. I wasn’t an ordinary alumnus. I didn’t buy the blazer, go to football games, come to Reunions. If I thought about Princeton in those years after graduation it was a “been there, done that” sort of thing. And probably a little “how could they do this to me?”

In the middle of life, I became involved with Princeton again. My work in publishing brought me to the University Press, where I served on the board for 20 years. This experience put me in touch with a Princeton that was new for me a place of intellectual excitement and curiosity.

It wasn’t new of course. That Princeton had existed all along and I was simply late to recognize it. One of my most vivid memories of Princeton was Professor James Ward Smith’s final Philosophy 101 lecture. As he wound it down, Smith turned his back to the lecture hall. He was quiet for a moment. Then, suddenly he turned and delivered his final thought, “Be amazed!” he cried and stalked out of the room.

That spark never died; it is a debt I owe to Princeton. Now, in my 80s, I have come to realize another debt to Princeton. It has to do with the uses of failure. Samuel Beckett put it best I think: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail better.” The undergraduates I have encountered at Reunions and elsewhere fill me with admiration. I would never get into today’s Princeton and that’s fine. But I — as I suppose it is with all us old alums — would love to have another go.

Jay Paris ’71

1 Year AgoAdding Berg ’71 to the List of Thesis Notables

Jimin Kang ’21’s excellent article about the vicissitudes of the senior thesis at Princeton — past, present, and future — reminded me of some true and some apocryphal stories that arose from my graduating class in 1971. In Kang’s examples of theses that lead to national distinction, I would add Scott Berg ’71’s work on Maxwell Perkins, editor extraordinaire to Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Thomas Wolfe, and many others. Berg’s thesis turned into a bestselling biography, the first of many that he has created to critical acclaim.

Frederick E. Lepore ’71

1 Year AgoTheses That Live On, Beyond Mudd Library

As the author of an unapologetically desultory thesis on the picaresque hero 53 years ago, I have utmost admiration for engaging theses which slipped the bonds of the Mudd Manuscript Library. Be forewarned that your list is incomplete without Scott Berg ’71’s thesis, which became Maxwell Perkins: Editor of Genius and garnered the National Book Award for biography (1980).

If Dean Eisenhart had prevailed with a senior thesis requirement a dozen years or so before 1925, we might be reading theses of nascent literary (or maybe callow) genius by the likes of F. Scott Fitzgerald 1917, Eugene O’Neill 1910, or in neuroscience, Wilder Penfield 1913. (OK ... the first two never made it to senior year, but it’s nice to speculate.)

If we can keep LLMs/ChatGPT at bay, I think Princeton has got a good thing going.

Swati Bhatt *86

1 Year AgoThe Role of Professors in Shaping the Senior Theses

Based on my experience as adviser of over 240 senior theses in the economics department over the past 30 years, I feel compelled to share my thoughts on the role of professors in shaping this academic journey. The senior thesis experience is the pinnacle of undergraduate education, offering students a platform to dive deeply into their chosen topic and demonstrate their research, writing, and analytical ability. However, behind many successful theses there were professors who not only demonstrated expertise in their fields, but offered constructive feedback and support during moments of uncertainty. Not only were the professors instrumental in refining methodologies, articulating findings, and providing constructive feedback, but they often took a genuine interest in the academic and personal development of their advisees.

Editor’s note: The writer is a lecturer in the Department of Economics.

John Simon ’63

1 Year AgoGetting Creative, on a Deadline

The PAW article on the history of the senior thesis (May issue) included a photo of Edward T. Cone ’39 and the information that his was the first work submitted as a “creative thesis.” This brought back quite a few memories for me.

Ed Cone was my mother’s distant cousin and probably the most compelling reason for my attending Princeton. I was a music major and, when thesis time came around, I applied to write a cantata based on the Garcia-Lorca play “The House Of Bernarda Alba.”

All was going well and, since I’d composed music since high school, I thought, “This is a piece of cake!” I submitted it two days early to my thesis adviser, the brilliant composer and educator Milton Babbitt *42 *92, who said, “Fine. Now orchestrate it.”

Holy Humperdinck! I had two days to take my piano score, break it down, and expand it into parts for a full orchestra! I went through boxes of No-Doz but got it done.

A year earlier I had put in a lot of work on my junior paper: “Simultaneous Composition In Jazz And Classical Music,” an examination of the music of Stravinsky, Ellington, et al. I got a disappointing grade. But, without my knowledge, Ed Cone read it and raised the grade. My J.P. adviser didn’t appreciate jazz. Ed Cone did.

David G. Robinson ’67

1 Year AgoThesis Trauma and a Recurring Nightmare

The recent PAW thesis piece honors the glories of the senior thesis, but doesn’t spend much time on the agonies.

As a Nassoon, I spent year after year watching my good friends senior to me go through the rituals of getting their theses done, such that I had acquired a good case of “thesis PTSD” by my senior year.

I hated my carrel, used only for working with books that had to say in the “libe”; wrote my thesis in a two-week marathon session of getting up at noon, eating lunch, then writing until 6 the next morning (visited nightly at 3 a.m. by the herds of cockroaches who lived in Laughlin Hall); and finished a pedestrian effort that earned me the Princeton equivalent of a B+, then graduated.

Looking back, I so regret the lost opportunity to really do something with my thesis (as I regret not majoring in history to study the 20th century, as I do now on my own). I also marvel at how that effort seemed so daunting looking back from much higher hills conquered in later life.

For decades afterward, I periodically had the thesis equivalent of the famous “exam dream” — It’s due today! Have I started it? Where do I turn it in? No wait, I was an early concentrator and actually wrote it last year — whew! Or did I? Ugh!

Richard M. Waugaman ’70

1 Year AgoInspiring Examples of Senior Theses

What a wonderful article, with inspiring examples of noteworthy theses. I’m now even prouder to be a Princeton alum. Thank you for highlighting the fact that Princeton alone requires a senior thesis. We’re all indebted to Dean Luther Eisenhart for having such confidence in Princeton’s students that he introduced the thesis opportunity more than a century ago. And it is a wonderful opportunity, not an onerous requirement!