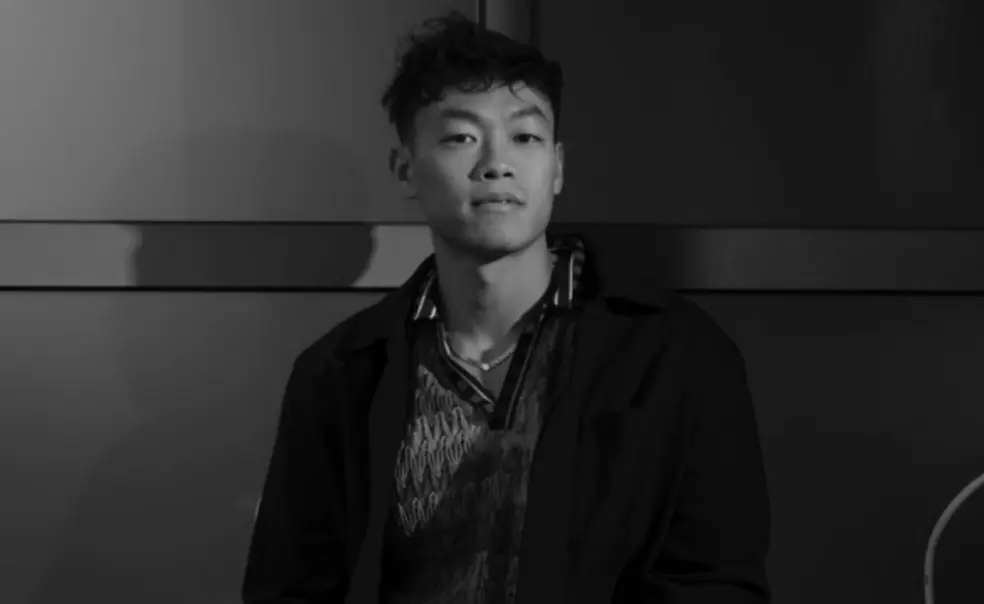

Simon Wu ’17 Reflects on Life and Self-Discovery

The book: In his debut book, Dancing On My Own (Harper Collins), Simon Wu ’17 reflects on art, capitalism, his life, and more through a collection of essays. In “A Model Childhood,” for example, Wu writes about the impact his mother’s clutter and desire to expand had on the family. Inspired by a 2010 song with the same title, Dancing on My Own by Swedish pop-singer Robyn, Wu’s writings meditate on the journey of life and the choices people make which dictate their future. His message to readers is to embrace the life-long journey of self-discovery and break free of the constraints placed on people by society.

The author: Simon Wu ’17 earned his bachelor’s degree in art and archaeology from Princeton. He is an artist and writer whose work has appeared in The New Yorker, The Paris Review, and Bookforum, among other outlets. In 2021, he was awarded an Andy Warhol Foundation Art Writers Grant. He is currently in the Ph.D. program in history of art at Yale University and is the program coordinator for the Racial Imaginary Institute.

Excerpt:

A Model Childhood

My mom calls me. She has found a house on Zillow. It has all the extravagant, absolutely necessary fixtures of suburbia: a three-car garage, central air, four bedrooms, two bathrooms, and twenty-foot ceilings. If my brothers and I used our money for a mortgage instead of rent, she says, we could live there together.

She wants to move to a bigger house. I think that we have too much stuff, but she would rather expand the container than shear down the contents. She moved us from our small town house in Philadelphia to the three-bedroom split-level in the suburbs we lived in for the bulk of my childhood. The current house sits on a steep hill, sheathed in vinyl siding the color of butter. It has box-cutter hedges and blue shutters, and a patio—a middle-class mirage my parents saved up for.

“You have to climb the rungs when you can,” my mom continues over the phone.

I imagine the rungs she describes as a ladder submerged in a grain silo filled with water. As she monitors the water’s rise from her raft, our current house, she eyes the next rung: higher, drier, safer. This rung would have a house with high ceilings and two staircases, rooms for all of us even if we are old enough to live elsewhere now.

“We want to set you all up for when we’re gone,” she says. “But maybe I won’t get to live in a house with high ceilings until my next life.”

Somehow, with talk of houses, we always come back to the subject of death.

When the pandemic began in 2020, I moved back in with my parents, and we started sorting through the things they had collected in their garage. There were boxes of children’s toys, piles of IKEA furniture from several college move-ins and move-outs, heaps of yard machines, and miscellaneous materials from the sushi kiosk my mom used to run at a college food court—things accumulated in the twenty-six years since they had moved to the U.S. from Myanmar. I considered most of this stuff useless, but my parents disagreed; they were things lying in wait to be used again. I avoided the garage because I felt at different times suffocated by, responsible for, and protective of everything in it. Most of the time, though, I just wanted to throw everything out.

That March, as the world closed down, I burrowed into this unwanted inheritance. I changed into workout clothes and set up a speaker. I worked my way through Katy Perry’s Teenage Dream, then Lorde’s Pure Heroine, then Robyn’s Body Talk, morale inflated on the engineered euphoria of pop music. I sat on a low stool in front of two open garbage bags—one for donation, the other for true death: trash.

I sang as I worked. And the singing let my brain disco while my body stayed in the garage. A makeshift karaoke booth in the lawn mower sea of suburbia. My hands moved on their own. My mom hovered warily as I slashed, with particular glee, through convention paraphernalia that we would soon be rid of: bottle openers, stress balls, and collapsible sunglasses. Children’s clothes, kitchen supplies, side tables, and TV cabinets. These made it to the donation pile, and the fact that someone, somewhere, would put them to good use nominally eased my mom’s melancholy.

I am often stymied by the persistence of my mom’s desires, desires that are not difficult to understand but difficult for me to inhabit. When we took a break from cleaning the garage to repaint the living room, she repeated the name of the paint color she had selected like a mantra—Benjamin Moore, Chantilly Lace, Benjamin Moore, Chantilly Lace. It was the color the internet had confirmed would be the most elegant white. She vacillated between outsourcing her taste to the blonde YouTube renovation women and sticking resolutely to her instincts. Sometimes I was impatient with her as she searched for approval online. I saw her outsourcing as weak and her intuition as stubborn. And then I judged myself for being cruel.

I was jealous of my friend’s houses, where there never seemed to be any clutter. Objects there could live simple, frivolous lives. A cereal box was to be used and discarded. A broken lamp was removed from sight immediately. A sofa could work part-time, collecting dust in a room full of furniture that lazed about in slovenly repose.

At our house, aesthetics were produced through resourcefulness; beauty was to be found in an object’s resuscitation from the edge of disuse. After the circuit broke on a floor lamp my mom found on the street, she brought it out to her garden, extracting the wire like a vein and staking the hollow rod into the soil, curling a waylaid pea-shoot tendril around it. Plastic water bottles were snipped in half to store pennies and paper clips; torn shirts used as mops; detergent boxes fostered Tiger Balm. Objects were made to live multiple lives, so that our life—this life, not the next one—would be perfect.

Take all our bookshelves. My mom used to enroll me and my brothers in reading competitions at the public library near our house in Philadelphia. The prize was an IKEA Billy—a sturdy, albeit plain, wooden bookshelf that came flat-packed in a dense rectangle. My mom collected us after school, and we’d check out entire shelves indiscriminately, reading everything between BET and COR, and the next week COR–DEK. This systematic method, combined with an actual appetite for reading, meant that we had a steady stream of bookshelves. We have six IKEA Billys, and they’re filled with board games and McDonald’s toys.

Consider the aesthetic theory behind this kind of decoration: incentivize your child to read books and, in the process, furnish your home. What the bookshelves look like matters less than how they were acquired; they are conceptual artworks where the process of procurement is the art, a material manifestation of scholastic achievement. This was the dumb amazingness of America, where bookshelves could be grown by reading.

The urge to collect crystallizes most clearly in my parents’ love for containers. They wash takeout Tupperware, store Starbucks paper bags, and keep Danish butter cookie tins. One time, I came home to find a neatly arranged stack of paper sleeves from Popeyes. They had once held chicken sandwiches, and my mom saved them because she said they would be great to store seeds and other snacks.

Containers are not possessions in themselves but rather a promise of the ability to store more things. They expand one’s capability to stockpile, and this is what is so entrancing about them. Collecting containers feels like winning. It feels like drinking from the bountiful rain of capitalism when others seem to be ignoring it.

“What a waste it would be to waste,” my mom once said.

When my father asks why we need to clear this stuff out, I tell him it’s because we don’t need any of it. “It feels like the stuff lives here instead of us,” I told him. I was righteous, and I was right. They needed fewer belongings; they needed to shed this survivalist mentality. All of this was fat to pad the vital organs from the impact of migration. And what better life vest to the turmoil of immigration than a fortress of containers.

Houses are the perennial favorite of Asian American writers as the preferred form of metaphorical and material repayment for the sacrifice of one’s parents. Houses and what they contain (a stray calendar, a stuffed animal, the promise of a son, etc.) are the stage, the repository, and the laboratory for experiments in the aesthetics of the diaspora. I don’t find myself exempt from this yearning, but I do find myself critical of it. Who, and what, do we leave behind in all this middle-class striving?

But also, I get it. Without this upward drive, how else could my parents have gotten me to where I am? There will be corners of this house that will always be dark to me.

Excerpted from Dancing on My Own by Simon Wu. Copyright © 2024 by Harper Collins. Reprinted by permission.

Reviews:

“A book that emerges out of the moment, electric with timely energies." — Washington Post

“Simon Wu manages to be both a shrewd critic and enthused aspirant of what passes for today’s cultural capital. Whether it’s ethically branded handbags, Asian American pastiche, initiatives for racial inclusion in museums funded by dark money, and the ever-increasing blurring of art and fashion, Wu unpacks it all with a disarming lack of cynicism that is both keen and refreshing. ” — Cathy Park Hong, author of Minor Feelings

No responses yet