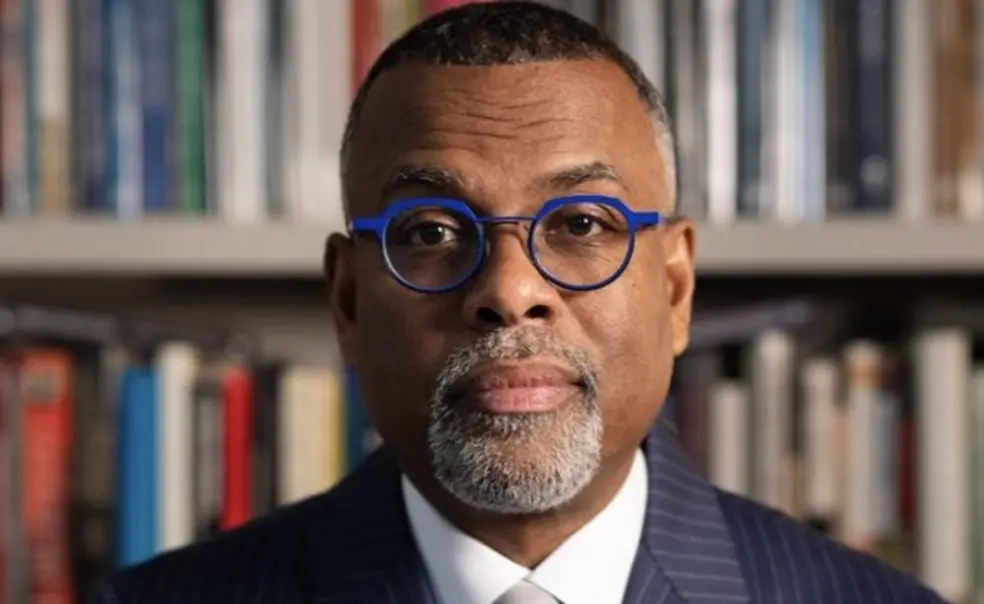

Eddie Glaude Jr. *97 on 100 Years of Black History Month: ‘I Find Hope in Our Story’

This year marks the 100th anniversary since the start of Negro History Week, which eventually evolved into Black History Month, celebrated each February. To mark the occasion, Eddie S. Glaude Jr. *97, professor of African American studies, spoke with PAW about Black History Month, understanding Black history in the present moment, and his upcoming book about race in America.

Can you talk about the significance of this milestone Black History Month?

I think it’s really important for us to understand the journey from then to now. In 1926, as the nation was celebrating its 150th anniversary, America was undergoing a wave of ugliness. It was the decade of the Klan, so in many ways there was this effort to render Black folk invisible, but Carter Woodson [who created Negro History Week] asserts the power of our contributions, our witness, our resilience, our grit, and insist that that’s part of the American story.

A. Philip Randolph [civil rights activist] spoke at the sesquicentennial celebration in Philadelphia, and in the midst of that speech he started laying out the history of Black folk. Obviously, they didn’t pay attention to him and redacted the speech from the final record. So here we are, in the 250th anniversary of the nation and the 100th anniversary of the celebration of our part in that history. We find ourselves in a space where elements of the country are trying to disappear us again. So we’ve told our story, and our story is not contingent upon the nation accepting it. We tell the story anyway.

How do you normally recognize and celebrate Black History Month?

Black History Month for me is all year. Usually I’m on the road talking about the challenges we face as a nation, thinking about race and democracy. Black History Month for me has always been part of the nation’s calendar to force it to understand itself. So I typically use it as a moment to call our attention back to the work we need to do when it comes to matters of race and democracy.

What are some meaningful ways for Americans to celebrate Black History Month?

Find a book by an African American author, whether it’s a novel or nonfiction, to immerse oneself in the experiences of African Americans to try to understand the country through our eyes. It could be Baldwin, it could be Toni Morrison, it could be John Hope Franklin, or anyone else. Also find some wonderful documentaries and sit down with them so you can see from whence we’ve come.

How do you reconcile celebrating Black history and achievements in this present moment that is in many ways trying to dismantle it.

It’s part of the vicious and maddening cycle of the nation. Gerald Ford was the first president to recognize African American history in 1976 and you see this attempt to absorb our story into America’s self-understanding. You get language like “a more perfect union,” or “We got a long way to go, but we’ve come so far.” By 1986, Martin Luther King’s holiday was signed into law by Ronald Reagan, and so the movement is ushered into the kind of pantheon of American history as our ongoing work toward a more perfect union. But in the current moment, the administration doesn’t give a damn about more perfect union talk. They actually take umbrage when we invoke that we still have a long way to go, because for them, America’s perfection was secured in the founding, and in order for that to hold true, you have to make us invisible. You have to move our story to the margins. One way to put it, and this is going to sound a bit harsh, but we are in a moment where so many of those in government and those who support this administration want to be white without judgment. To be white without judgment requires our silence.

Then how do you find hope?

I find hope in our story. Remember, we didn’t tell our story because they accepted it. A. Philip Randolph, said, and I’m paraphrasing, if there are true Americans in this country, we are them. Black people have always had their own freedom calendar. Instead of celebrating July 4, we celebrate July 5 to mark the day slavery ended in New York state. We commemorate Juneteenth and West Indian Abolition Day. So in this moment, we don’t clutch our pearls, we tell our story and we stand in it, full chested.

What words or lessons have you returned to help navigate this moment?

I just finished writing a new book, it’s titled America, U.S.A.: How Race Shadows the Nation’s Anniversaries and I looked from 1876 to 1926 to 1976 to 2026. I’m in conversation with Du Bois, Baldwin, and Toni Morrison, trying to find resources to give voice to a kind of resilience and rage at the fact that here we are in the 250th year of the nation, still dealing with this madness. Typically I reach for Baldwin, but in so many ways, what I’m trying to do in this book is to reach for what’s in me — this distillation of the tradition that comes to me to give voice in this time. Again, our celebration of Black history isn’t contingent upon the White House acknowledging it, and we have to understand that. Baldwin says that the nation had to grow up, and in some ways, in order for it to grow up, it would have to confront us. You know what, it still has to make a moral choice. Will it be a beacon of freedom or will it simply be a white republic?

What inspired you to write the book, and what do you hope readers will take away from it?

I was trying to make sense of things. The contemporary moment is so fluid, it’s hard to put your pen on something. In order to understand the present and what is needed in this moment, it requires a robust understanding of what we want and what makes us who we are. I decided to reach back. How could I tell a 250-year history of the country without writing 250 years of America? So these milestone anniversaries are these moments when the nation had to tell a story about itself, and in each of these moments the nation is confounded by its original sin. The year 1876 marks the end of Reconstruction, 1926 the racism of the Klan and nativism, 1976 the busing, where we see that iconic photograph of the young man in Boston attacking a Black man with the American flag. In these moments when the nation tries to find comfort in its myths, our story sticks its head out and says, no, it’s much more complicated than this.

What do you think the story of today will ultimately be?

They believe that the country is theirs. They believe that we should shut up and be grateful. They have doubled down on the idea that America is a white republic. Our task is to refuse. Black people know that America would not be America without us. We are distinctly, definitively American. In my Baldwin seminar a couple of years ago, one of my students said at moments she loves the country and then at other moments she’s just full of rage at what the country stands for. In her final paper she wrote, and I’m paraphrasing, that maybe we can’t be hopeful, but we can bear witness to tell the truth with love lit by rage. That is our task.

Interview conducted and condensed by C.S.

No responses yet