The Thesis Challenge: Looking Back at a Capstone Experience

Joe Ryan ’83 admits that in the classroom, he was not an exemplary student. But on the water, it was a different story. For his senior thesis, Ryan, graduate student Ann Maest *84, and adviser Bob Stallard navigated the shipping channel of the Raritan River in a 20-foot boat, meticulously collecting samples (and occasionally dodging oncoming tugboats). Ryan would then return to the lab for analysis and write up the results at his desk in the basement of Guyot Hall.

“For me, it really opened up a strong interest,” Ryan says, “and I discovered an ability that I hadn’t really demonstrated until then.”

After working for a couple of years at a consulting firm, he pursued a Ph.D. in environmental engineering at MIT and landed a faculty job at the University of Colorado, where he’s spent the last 27 years.

Ryan was one of the dozens of alumni — with class years ranging from 1955 to 2018 — who responded to PAW’s recent call to take the “thesis challenge.” They re-read their theses and shared their reflections in interviews with PAW staffers. The experience sparked a range of emotions, mostly positive save for a few cringes over typos or pretentious vocabulary. The feeling from readers was that their theses held up pretty well, or at least better than expected.

Alumni recalled doing research in the mountains of Greece and the churches of London, interviewing high-ranking officials in D.C., and finding diversions that helped them carry on during long hours in the library or lab. Among the more memorable study aids: malted milk balls. “I couldn’t take the books out, because it was a closed-stack library,” recalls art and archaeology major Julia Hicks de Peyster ’86, “so I had these really nice friends who would stop by, cheer me on, and drop off malted milk balls.”

Conversations traced technological changes in thesis writing, from lugging around portable typewriters to loading punch cards to locating a campus computer lab with late-night hours. Alumni also recalled the anxiety that the yearlong project could engender. History major Melissa Stuckey ’00 was particularly worried about losing her drafts and notes. “I just remember thinking, ‘If Butler catches on fire, I am going to throw, as far as I can, all of my documents out of the window,’ ” she says. “Not logical, but I certainly had a fire plan.”

Tisha Thompson ’99 says she still occasionally has nightmares where she hasn’t started her thesis and she’s not going to be able to get it done on time. “It is the ultimate anxiety dream for me,” she says with a laugh. “I got started on my thesis in my junior year, so I don’t know why that stresses me out to this day.”

Read capsules from each “thesis challenge” conversation below

Thinking about the thesis brought back memories of beloved advisers, including longtime faculty members Walter Kaufmann, Elaine Showalter, and David Billington ’50. Stephen Buonopane ’91, now an engineering professor at Bucknell University, flipped through pages of notes that Billington wrote during their weekly thesis meetings. “I have many memories of sitting with David and saying, ‘I don’t understand this equation,’ and he’d look at it and say, ‘Well, I’ve never seen it before. Let’s figure it out together,’ ” Buonopane says.

Our volunteers also looked to the future, sharing advice for the next generation of thesis writers: Follow your passions, don’t procrastinate, and immerse yourself in the experience.

“The biggest thing is not to treat it like a chore — treat it like a gift,” says Sarah Marmor ’87, a comparative literature major who wrote about Joseph Conrad, Albert Camus, and E.M. Forster. “It’s a gift in life to be able to find something that interests you and spend months just toiling at it.”

Jason Albert ’92

Thesis: A Tectonic Interpretation of the Eastern Beartooth Mountains, Montana and Wyoming (Geosciences)

Self-grading: “As I was reading through and thinking about what questions I would ask, the thesis actually answered them later on. So my sense — and admittedly, I haven’t done geology in 27 years — was that it held together pretty well.”

Research Memories: “I remember spending a lot of time doing the cross sections because we were using a Macintosh program. There was only one Mac in the geology department that was powerful enough to run it, and graduate students had it during the day. So I remember always doing it at night. I knew it was time to go back and get some sleep when the person came in to clean in the morning.”

Lessons Learned: “By [senior year] I had really decided that I wanted to go to law school. My father was a lawyer and I’d always wanted to do that. I really enjoyed being a geology major — I enjoyed the science, I think the inductive reasoning really helped. ... It was fun to revisit this because it is so different from what I do day to day.”

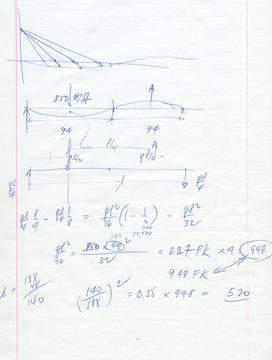

Stephen Buonopane ’91

Thesis: Theory and Experience in Suspension Bridge Design (Civil Engineering)

“[Adviser David Billington ’50 and I] set out to answer some questions about John Roebling, based on his first two bridges, which were built in Pittsburgh in the 1840s [and] no longer survive, to try to understand how those bridges connected to the Brooklyn Bridge. What did he learn from these early bridges that made it possible to build the Brooklyn Bridge? The research ended up going in a different direction, which was to try to understand what happened between the time of John Roebling and the mid-20th century, when the famous collapse of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge occurred.”

Research Memories: “I remember there were times when I had so many books laid out on my bed that I slept on the floor because I didn’t want to put them all away.

“I met almost every week of the academic year with David, and we had serious discussions about what I was doing. … When you’re a student and you go to your adviser with a question, you think they know the answer and they’re not telling you, because that’s sort of what classes are like. But [in research], you realize that the professor doesn’t know the answer either — that’s why it’s research. Struggling together is a really intellectually stimulating experience … and certainly frustrating at times, too. I have many memories of sitting with David and saying, ‘I don’t understand this equation,’ and he’d look at it and say, ‘Well, I’ve never seen it before. Let’s figure it out together.’”

Lessons Learned: “It was the single most positive and engaging experience that I had at Princeton. The fact that you’re required to spend a year digging into something, making it your own, taking responsibility for it, and asking questions that probably no one else has asked before — that was just really rewarding, and all-consuming for me. … I’m still using notes that I took in 1990 to do new research.”

Monika Cassel ’92

Thesis: A Wilderness of Language: Mapping Landscapes of Self-Representation in the Works of Emily Dickinson and Paul Celan (Comparative Literature)

“When I was brainstorming thesis ideas with my adviser [Virginia Jackson *95], I said that I like poetry, I like Emily Dickinson, and I like Paul Celan. She said, ‘Did you know that Paul Celan translated 12 of Emily Dickinson’s poems?’ And so, there I was with a post-war, post-Holocaust Jewish poet who seemed worlds away from Emily Dickinson and Amherst in the 19th century, and I was completely intrigued by what would have drawn him to translate her poems.”

Self-grading: “I was expecting an earnest, detailed, passionate piece of writing that gets lost in the weeds. … I was really hung up on the idea that language cannot give you the tree, it can only give you a translation of the tree, and that really bothered me at the time. I wanted art to be life. That’s kind of what I ended up writing about, and looking back, I think that’s a naïve viewpoint. But the pleasant surprise is that although I started with this naïve viewpoint, [the thesis was] more interesting than just ‘all art fails.’ And that was exciting.”

Research Memories: “There was a sort of index for all of the words in Emily Dickinson’s poems and then the same for Paul Celan. I was looking up a key term, the meridian, which occurs in a speech that Celan gave, a poem of his, and one of Dickinson’s poems. I remember being down in Firestone and looking up those words. And I remember writing out the poems longhand and trying to understand them.”

Lessons Learned: “I’m grateful to have had the experience of being challenged to think so deeply, both in terms of what the University expected and in terms of my work with my adviser, who was an emotional support as well as a person who pushed me to be my best.

“I have come full circle to being a poet and a translator myself. I translate German poetry and am particularly interested in some of the same questions that Celan was interested in — German history and reckoning with the Holocaust. … So I’m no longer a scholar in the same sense, but I feel like the reading of poetry taught me how to be a writer.”

Christine Charney Cook ’86

Thesis: The Effect of World War I On Sex Roles as Seen In the Works of Willa Cather and Ernest Hemingway (English)

“At the time, feminist literary criticism was relatively new. I was applying feminist literary criticism to a male writer, Ernest Hemingway; and traditional criticism to a female writer, Willa Cather.”

Self-grading: “Thirty-something years have gone by since I read it. I expected it to be a senior effort. And it was better than I thought it would be, although there were certain things that I wouldn’t do now. I would not start a sentence with, ‘It is interesting to note that…’ … And there were a couple of times where I thought, ‘Oh, I wish I had pushed that [idea] a little bit further.’ ”

Research Memories: “I used the summer to do the majority of my research, before I even began the thesis itself. I read virtually everything possible by Ernest Hemingway and Willa Cather and determined which books I would be using for the criticism. And then I basically tried to get a chapter written every two months.”

Lessons Learned: “My thesis was 65 pages long. Up until that point, that was the longest thing I’d ever written. … It helped me to figure out how to do ‘long-distance running,’ so to speak. I realized that I wasn’t a sprinter … and that long-term writing projects were a better fit for me. [Today, Cook is a Ph.D. candidate in history, preparing to write her dissertation.] I’m not really all that worried about trying to write 300 pages. It’s a senior thesis on steroids, and I can do that.”

Merritt T. Cooke ’76

Thesis: Theories of the Evolution of Consciousness: A Critical Evaluation (Religion)

“Both of the religious thinkers that I looked at, one Western and one Eastern, used evolutionary concepts at the basis of their religious thought. … The two thinkers are not household names by any stretch. The Western thinker was a French Catholic theologian named Pierre de Chardin, and the Eastern thinker was [Indian philosopher] Sri Aurobindo.”

Self-grading: “I went on to U.C. Berkeley and did Ph.D. in cultural anthropology, and I actually believe that the design of my senior thesis at Princeton was a better and more elegant design than what I ended up doing for my Ph.D. dissertation. So I’m proud of that.”

Research Memories: “I had rowed for three years at Princeton, and I chose not to row my senior year for two reasons: one, because I had a nagging knee issue, but also, equally as important, because I wanted to do a good job on my thesis. It seemed that [rowing and the thesis] were going to be incompatible.”

Lessons Learned: “I had a great deal of curiosity about Asia and the East. … The thesis was a starting point of what’s been a pretty clear trajectory in my life. I did not stay in academics; I wanted to get more involved in Asia, not just teach about it. So I joined the U.S. Foreign Service and had a very satisfying career at our posts in China, Japan, Germany, and Taiwan.”

George Dawson ’59

Thesis: German Views of the American Civil War (German)

“Somewhere along the line, I learned that there were, in the United States, five complete German publications that covered, among other things, the period of the Civil War … and three were in Firestone. … When I took [the idea] to my adviser, I thought he was going to blink. He said, ‘I think that would be a good topic.’ And I thought, ‘Here’s another guy who’s tired of Faust and Rilke and all that stuff.’”

Self-grading: “I re-read it and I found a sentence or two where I thought I could have improved the structure of it and made it read a little more smoothly. But I’m quite satisfied with it. It’s a good read. Though I can’t quite understand all the German quotes I put in because I’ve forgotten German.”

Research Memories: “I added it up: 3,283 publications — one was a daily and the other two were weeklies. I read every issue of every one of them, looking for articles on German opinions of the Civil War. My carrel-mate was totally absent, and that was fine because my carrel was just full of publications — seven years’ worth of stuff to go through.”

Lessons Learned: “I discovered later on in life that I was a history geek, and this was an early sign of it. … For the last 18 years, I’ve been volunteering with the National Park Service at the San Antonio Missions National Historical Park.”

Julia Hicks de Peyster ’86

Thesis: Miro and the Influence of French Poetry Before 1927 (Art and Archaeology)

“It was written about the French surrealist poets and their relationship to [the Spanish artist] Miro. Miro thought that painting and poetry came from the same creative source. He happened to be a painter, but he was doing the same process as the poets of the day.”

Self-grading: “What you were taught in high school was to find an interesting thing and tell people about it — you weren’t necessarily encouraged to have an opinion. Then in college, a great deal of your opinion was about citing someone else’s opinion and refuting, or agreeing with, the scholars. It was hard to have an original thought. … I don’t think anyone out there had written an 80-page paper looking at [Miro’s connection to poetry]. So did I say something new? Sure, because nobody had bothered to look at it. But did I say something new about modern art or poetry and painting in a community of people who are making art? Probably not.”

Research Memories: “I could not have done this without malted milk balls. I couldn’t take the books out, because it was a closed-stack library, so I had these really nice friends who would stop by, cheer me on, and drop off malted milk balls.”

Lessons Learned: “I thought of myself as somebody who could have gone on to a higher education, and I realized that I’m such an extrovert that I cannot possibly do a job where I stay alone for large quantities of the day. It was really useful to make me realize that scholarship was not the thing for me. The thesis is kind of like the sorting hat, and I was not chosen for Slytherin. … But you get a lot out of it, not just the scholarship.”

Selden Edwards ’63

Thesis: Awareness and Response (Religion)

“I chose to write about Albert Camus. … His heroes were existential heroes, who stepped out of the norm and, in a romantic sense, committed to serving humanity and being something special. So, once they became aware there was a need, they responded.”

Self-grading: “I tried for 30, 40 years to publish stuff and I couldn’t get anything published and then all of a sudden this miracle happened, and I’m a famous novelist. So I thought, what was my writing like in college? If I just read it like an editor, what would that be like? And I was impressed, actually. You rise to the occasion. I had wanted my thesis to be the very best it could be, and I worked really hard on it.”

Research Memories: “Everybody did [a thesis], and it was a very serious senior year. Senior year at Princeton was a very meaningful experience. Departmental requirements were what made the Princeton experience powerful. So senior year, when seniors were knee-deep in their theses, it was dead quiet. Everybody was in the library. It was serious stuff, and I loved that. It was being taken seriously — when you didn’t necessarily earn it — by raw talent. For me it was a life-altering experience.”

Lessons Learned: “Write, write, write. Never stop writing. If you don’t write then you can’t suddenly be meaningful. It’s like calisthenics; it’s that daily exposure to serious critical thought that is the answer to the whole thesis experience.”

Guillermo Elizondo ’00

Thesis: Option Zero (Or How I Stopped Worrying and Love the Cuban Revolution) (Politics)

“My thesis is about the Cuban economy after the collapse of the Soviet Union. … In all the literature about Cuba, everyone thought the regime was going to collapse, and everything that was written about the economy was about what to do to fix it and reconnect it to the world once the regime collapses. I decided to write about what the Cuban regime was actually doing so that it wouldn’t collapse.”

Self-grading: “I was going through pretty fast, and a lot of things came back [to me]. I kind of surprised myself. Someone who’s not familiar with this topic would get the picture right away and be able to understand what’s going on. … Researchers and Ph.D.s were saying that this year or next year, the Cuban regime is going to collapse, and here I was, a little undergrad, saying, ‘No, you guys are crazy, that’s not going to happen.’ So I can see their point of view, but the information that I had led me to this conclusion. And it’s flattering to see that I was correct.”

Research Memories: “I had a difficult time finding the correct numbers and resources at the time, and that was frustrating. But looking back, that was also kind of fun. … I had to make do with the documents that I could find. There was a specialized academic database for Latin America, curated by the University of Texas, and that was the primary source.”

Lessons Learned: “During my research, I came across brief mentions of how Cuban agriculture and survival gardening developed without artificial fertilizers because they did not have access to them. … [Today] there’s a lot of interest in Cuban farming because they had to experiment with permaculture, organic gardening, and container gardening, and they developed techniques on the fly. It has become a model [for sustainability].”

Molly Fisch-Friedman ’16

Thesis: To Bibi or Not to Bibi: American Public Opinion of Israeli Prime Ministers, 1994–2015 (Politics)

“In my junior year, I took a course in public opinion, and I thought it was super-fascinating. I liked that it was a very quantitative way to think about political science. … So when it came time for my thesis, I knew that I wanted to work with polling data and use numbers to test a hypothesis and really get at the questions you want to [answer].

“And I am very proud of my thesis title. … It is probably the best pun that I will ever make.”

Self-grading: “I wasn’t sure what to expect because when I wrote it, I’d taken one class in public opinion and had a little bit of experience with quantitative data analysis, but now I’ve done so much more work in [the field]. … It was nice to remember all the hard work that I put into it.”

Research Memories: “There hadn’t been a lot of recent academic work on American public opinion toward foreign policy, and specifically in the Middle East. I worked very closely with the politics librarian and the data-science librarian. They helped me immensely. I spent many, many hours in the data lab in Firestone, working with the librarian to help me figure out the best analyses to run and how I was going to run them.”

Lessons Learned: “When I was writing my thesis, it was just something that I thought was interesting — and it’s become what I spend so much of my time doing [professionally], but not because I had this big plan of what I wanted to do. I feel very grateful — it has been a very happy turn of events.”

Stephanie Blackburn Freeth ’97

Thesis: Rewriting Female Friendship (English)

Self-grading: “I sat down and read it cover to cover, in a couple of hours, and thought, ‘This is pretty good!’ It flowed, it made sense, it felt like sophisticated language for a college student. … It’s interesting to see what you’re capable of academically but also emotionally at that stage of your life. There’s kind of a ceiling [to what you can explore] based on what you’ve experienced in your lifetime.”

Research Memories: “Elaine Showalter was just such an amazing mentor — that was one of the highlights, getting to work with her. She did want me to have a draft done by Christmas, which most professors don’t require, and looking back, I’m so thankful that she did that. I was able to build on my junior papers, and having a draft before Christmas meant that I was able to refine it during the spring.”

Lessons Learned: “[In my career], I ended up writing a strategic-planning workbook for nonprofits — it’s 167 pages — and I would have never sat down to write that if I hadn’t gone through my thesis process. I knew I could do it. I identify as a writer and a researcher — as someone who is passionate and curious about generating original thought. … That has stayed with me, all these years later. And I definitely think there are more books to come from me.”

Robert Good ’71

Thesis: Exposition and Critique of the Philosophy of Merleau-Ponty (Philosophy)

“Halfway through my college years, I developed a passion for continental philosophy, European philosophy, especially Jean-Paul Sartre, Martin Heidegger, and the person I eventually did my thesis on, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, the French phenomenologist.”

Self-grading: “I wasn’t expecting it to be very good. But when I read it, I realized that some of the criticisms that I made of Merleau-Ponty and some of the evaluation I made of him and others was really pretty good for an undergraduate. It certainly doesn’t compare in quality to my published articles as a professor, but then, what would?”

Research Memories: “There had been some research done on Merleau-Ponty, but not a lot. Firestone had a pretty good selection of secondary sources, and this was back in the days when we had carrels. … I remember walking to Firestone every day, determined to finish the thing by April, [and] staying around for spring vacation, rather than traveling. I also remember typing it myself. … I had a little Royal portable typewriter that I carried around in a suitcase.”

Lessons Learned: “The Princeton philosophy department was rather intimidating at the time because it was ranked No. 1 in the country and the professors were held in awe. I was very nervous when I was writing the thesis, but I think that certainly motivated me.

“What the thesis did for me is it helped me work through a fear of failure. … And it’s something that I think helped me in future challenges, where you’re speaking in front of a large group of people or you want to send off a journal article but you’re thinking that it’s not good enough. If you just keep working and being conscientious, things will probably be OK in the long run.”

Bill Goodman ’73

Thesis: “Self” and “Sombra” in the Poetry and Drawings of Federico Garcia Lorca (Romance Languages and Literatures)

Self-grading: “I thought it was a big failure, and that’s why I didn’t want to look at it, in all these years. … [But when I re-read it], I was astounded. I thought, ‘This is good! I wrote this? Really? Look at that — oh my goodness, that’s great!’ I got about halfway through it with this amazing feeling. After 46 years, it completely turned my concept of the thing on its head!”

Research Memories: “I had to convince everybody that foreign study was a good idea. They didn’t do [study abroad] back then. … Northwestern University was running a program out of the University of Madrid, and I had to join that program. Maybe it wasn’t Ivy League-level, but most of the people were over there for a cultural experience.”

Lessons Learned: “Lorca was repressed about [being gay], so if there was anything to be found in the poetry, it was between the lines. And what I found out again by re-reading this is that I was repressed about it — I was the same way. Here I was trying to put forth this theory and being very closeted and between-the-lines about it myself. I was reserved and reticent to talk about what was definitely there.”

Rebecca Rasmussen Grunwald ’77

Thesis: Cultural Center for a Permanent Olympic Site at Olympia, Greece (Architecture)

“Bill Bradley [’65] was very involved in the idea that there should be a permanent Olympic site, given what had happened in Munich and also just given the expense of building stadiums and [other buildings] that were being abandoned all over the world. … Four of us started talking about how interesting it would be to design a whole plan for this. We made an agreement with the architecture department that we would develop the site plan together and then each of us would take an individual building and work on that for the second semester.”

Self-grading: “Honestly, the written part was really thin. But when I looked at where I talked about the experience of developing a plan and deciding on the site, it was really an introduction to what I do now [as an architect]. … Stylistically, you would be able to say that it’s a late ’70s or early ’80’s building, but I actually felt it was laid out pretty well. The design project itself was pretty good.”

Research Memories: “We decided that we needed to go [to Olympia], and we got a list of everyone on campus who had a discretionary account. … We put it together with a string, and a lot of different people contributed. We were very bold. We got to meet with the prime minister of Greece [Konstantinos Karamanlis], who thought this was a great idea. We met with the permanent Olympic Committee. … We spent time trekking around Olympia, looking for sites.”

Lessons Learned: “Knowing how to ask the questions. Part of architecture, before you start designing and while you’re designing, is that you need to know how to ask yourself questions. Having the ability to do that at a very young age gives you the strength to continue doing so.”

Jay Haws ’58

Thesis: John Woolman: The Quaker Spirit in Colonial America (Religion)

“John Woolman was an activist Quaker in the Colonial period and was particularly active in trying to abolish slavery within the Quaker community.”

Self-Grading: “I think the overall criticism [in comments from my adviser and second reader] was correct. Being young and not so sophisticated, I was too positive in describing Woolman and didn’t look at the criticisms of him. … He was a very rigid, conscience-driven man who didn’t give much leeway.”

Research Memories: “I put a lot of effort into it. I went down to Swarthmore and looked through lots of Quaker minutes. Those were the days when the electric typewriter was the fashion, so it took forever to write things. One of my friends at Princeton — who I went through high school, Princeton, and med school with — came up to me when we had turned our theses in and said, ‘Haws, let me tell you something: This is the closest we’ll ever get to having a baby.’”

Lessons Learned: “My first advice would be don’t procrastinate. Get started on it the summer before because it’s going to take a lot of time and effort if you want to do a decent job. And the other advice is to put your own creativity into whatever you’re writing. That’s what the professors really want.”

Vera Vaughan Hough ’92

Thesis: Little Songs Out of Great Sorrows: The Value of the Confessional Lyric (English)

“I wrote about four woman poets — Edna St. Vincent Millay, Dorothy Parker, Sara Teasdale, and Louise Bogan — arguing that their work showed a uniquely feminine poetics that valued form, intimacy and connection in contrast to the innovation and detachment of Modernism. I specifically explored how they wrote about relationships in light of the work of feminist social theorists Carol Gilligan and Nancy Chodorow.”

Self-grading: “The confidence of my argument was quite impressive. I have this affection for the young me who made these arguments with force even though I’m not sure I agree with those arguments now. I was also surprised by the facility with which I used academic terms. I was at the top of my game.”

Research Memories: “I enjoyed the sheer act of writing it, which I did in the carrel room in the second floor of Tower Club. There was a group of us who all worked on our theses at the same time in that room on our Mac SEs. We all developed special relationships that still exist today — a community within a community within a community. [Case in point]: The person in the Tower Club carrel right next to mine is now my husband, Richard R. Hough III ’92.”

Lessons Learned: “I’d tell current students to put yourself on a regular schedule, plan the work out, and see your adviser. I sort of didn’t want to bother my adviser, but your adviser is your adviser, ideally, because they have a lot in common with you. They’re there to help you.”

Nicholas R. Howe ’93

Thesis: A Statistical Measure of Phase Correlation in Large Scale Structure (Physics)

“At the time, researchers had developed various computer simulations describing how the early universe might develop under different theoretical models. The question was how to compare those simulations to what we actually observe in the real universe, trying to figure out which of the models are actually plausible. My thesis developed two different statistical methods to compare the simulations with real data, as a partial answer to this question.”

Self-grading: “It was nice to go back and take a trip down memory lane. I actually was impressed by how carefully I had produced it.”

Research Memories: “[As a computer-science professor at Smith College] I have students doing theses with me now as undergrads, and the thing that’s hardest for them to understand is how quickly the time goes. You always have less time ahead of you than you think, so you need to get working faster than you think. And that’s not something I was aware of as a student, even though I certainly knew that intellectually.”

Lessons Learned: “I didn’t major in computer science as an undergrad — I didn’t even take programming courses at Princeton. My thesis was on physics, but it was a computational thesis — that was a big part of making that realization that I wanted to make the change to computer science. So I wanted to go back and look at some of the coding. On the one hand, I was impressed with myself for having some interesting ideas, on the other hand, the code itself is pretty simple. That particular part was not impressive.”

Dennis Kelly ’70

Thesis: A Reassessment of the Just World Hypothesis in Light of Attribution Theory (Psychology)

“There was a study where a couple of social psychologists [proposed] that if someone is perceived as being a true victim, or altruistic in their suffering, there will be a tendency to reject the victim. There’s a cognitive dissonance factor that says innocent people shouldn’t suffer because then it isn’t a just world. We have to believe the world is just.

“[In recreating the experiment], I added other conditions that the first researchers didn’t add — they just sort of assumed that people would ascribe responsibility to the person [in the videotape they reviewed]. And I found totally different results.”

Self-grading: “Reading back through it, I thought I did a commendable job. I probably got a little wordy at parts — I’d be a little more sparse with my words now — but I was impressed with it.”

Research Memories: “I was taking an introductory computer course, and there was some sort of a rudimentary word-processing program where you could take your work to the computer center and it would print up for you, justified on both sides. But you had to put everything on [punch] cards — one line per card. So that’s how I printed my thesis. I had a huge box of 8,000 cards. You would feed it into this card reader, and it would go ‘ka-chunk, ka-chunk, ka-chunk … ,’ and then wait, and it would print it out. I remember at the time we were so impressed with that. How times have changed!”

Lessons Learned: “It was a good springboard. I made a shift from social psychology to clinical psychology and then to clinical neuropsychology, working more with patients. But the thesis helped me think about psychological problems and adopt a scientific approach to testing those [ideas].”

Kar Min Lim ’16

Thesis: Between Empires: Chinese Immigrants in the Spanish Philippines and the British Invasion of 1762 (History)

“I grew up in Singapore and was very interested in Chinese history. When I came to Princeton, I took Spanish for the first time and really liked the language. I took a class on early modern Spain, and was also interested in the Spanish empire. … It brought together all of my geographical interests and my interest in immigration and the experience of immigrants.”

Self-grading: “I was struck by how personal the thesis was for me. It brought together a lot of my interests, and re-reading my acknowledgements page reminded me of all the people, academically and personally, who helped me through that time.

“Obviously the thesis is not perfect … but I was kind of surprised at myself and how I managed to pull it off with the sources I pulled together — reading 18th-century sources in Spanish, a language I hadn’t spoken before coming to Princeton. … I was sort of impressed by my college self.”

Research Memories: “When I landed in the Philippines, it was monsoon season, so the first two or three days I was stuck inside the dorm room at the university where I was doing work because it was totally flooded outside. And at the same time, I was reading these sources about how geography and climate condition the way of life and the development of society in the colonial Philippines. So that connection made it very real.”

Lessons Learned: “A lot of the skills that I honed in history are actually really similar to the things I do now in management consulting. In the business world, the content is very different, but at the same time, looking at the thesis and seeing how I was trying to piece together these incomplete sources of information to solve a puzzle, the skills are similar. … The thesis was a capstone for what I did at Princeton, but it also, in an unexpected way, prepared me for what I’m doing now.”

Spencer MacCallum ’55

Thesis: American Indian Art of the North Pacific Coast (Art and Archaeology)

Self-grading: “It came back to me very clearly. I’d always thought I did a good job, the best I could, and I was really impressed with the quality of the research and the writing. I was glad to read it.”

Research Memories: “I got in touch with anthropologists, Erna Gunther in particular, and they were surprised and delighted. They had known about this collection but had no idea what had happened to it, where it had gone. … Several dozen pieces were displayed by Gunther at the Seattle World’s Fair, where more than a million people saw them.”

Lessons Learned: “The art was like heraldry, but much more complex and developed than our tradition of heraldry. And the way it worked and served functions in the society was fascinating to me. … The art really grasped my soul and never let go. I don’t know of another as-sophisticated style as the Northwest Coast, anywhere in the world.”

Jim MacGregor ’66

Thesis: National Defense Student Loans: Enrollment Equity and National Income Effects (Economics)

“The federal government had never loaned money to students before. But Sputnik had gone up, and there was a huge panic about why we were falling behind in the brain race — why don’t we have more scientists and mathematicians? President Eisenhower conjured up the National Defense Education Act, which was going to loan big chunks of money to get more people to go to college. … So the question was, is it going to work?”

Self-grading: “The writing was actually pretty good. The thinking was OK, but there was a bunch of stuff that either I couldn’t have imagined or that I should have imagined but didn’t. … My adviser [Rudy Penner] left Princeton and went on eventually to become head of the Congressional Budget Office. The best hour I spent with him was one where he was talking about forecasting. He said that when you’re looking into the future, being precise means you’re almost certain to be wrong. Your only goal is to get into the right ballpark, and he provided an instant tutorial in how to think about a question in a way that will lead you to the right ballpark.”

Research Memories: “In those days, none of the information you wanted was going to be found easily. What’s the difference [between the] lifetime income of someone who graduates from college and somebody who stops after high school? It took me hours, over a period of weeks, to find and gather enough information to make my own calculations. … Yesterday, I googled those questions and had answers to both in under 20 seconds.”

Lessons Learned: “The simple fact of [finishing the thesis] is in fact a major achievement — getting that deep into a subject and then getting something done, under time pressure.”

Sarah Marmor ’87

Thesis: The Exotic-Colonial Adventure: Three Views of the East (Comparative Literature)

“I read both Heart of Darkness and Passage to India in high school, and there were these absolutely significant, major moments in each book, but I wasn’t mature enough to [fully] get what they were. … I also read Orientalism, by Edward Said [’57] … and thought that it didn’t allow for the possibility that great literature could transcend some of the clichés of orientalism. So that’s what I decided to write my thesis about.”

Self-grading: “I was surprised that I could write an entire chapter in French — I couldn’t do that today. … The main reaction I have reading it, and it’s been the same every time, is that I’m slightly horrified by some of the words I used, like ‘synecdoche.’ … [Today] as a lawyer, I’m not shy about using complicated words if they’re the right words. But I prize clarity of expression over highfalutin-ness of expression.”

Research Memories: “I really lived my thesis. It became everything to me. … I remember walking through campus very late at night with two of my classmates, one of whom was my boyfriend at the time, and we all were doing theses on completely different things, but it felt to each of us as if our thesis was really about everything in life.”

Lessons Learned: “The biggest thing is not to treat it like a chore. Treat it like a gift. It’s a gift in life to be able to find something that interests you and spend months just toiling at it.”

Rory Remer ’68

Thesis: A Statistical Analysis of Flat Horse Racing (Mathematics)

“I dedicated it to ‘my father, who plays the horses, and my mother, who would wish he wins.’ … The primary outcome, which makes a lot of sense, was that your best bet was the horse that had run the fastest at that distance previously. It didn’t make enough distinction between or among the entries to actually say that one horse was so far superior to the others that it was worth putting a lot of money on. But it did give you some idea of a number of horses that were close, if you wanted to bet something like a trifecta or an exacta.”

Self-grading: “I had looked at the thesis, but not much over time. More often, I would go back and look at my [doctoral] dissertation. And what pleased me more than anything else, both when I looked at the dissertation and the thesis, is that I wrote better than I thought I wrote. I didn’t like to write; I like it a little more now. … What struck me is that I was very clear — a lot shorter and more concise than I tend to be these days.”

Research Memories: “Computers were somewhat of a novelty. The amount of computing power that you have in your phone today is probably more than was in the whole building where the computer center was. … [My statistical analysis] was really an application. I went in and created variables, entered data, and did different kinds of regressions to get some results. It made for some pretty interesting ways of looking at the information that you got on a racing form.”

Lessons Learned: “In many ways the thesis was beneficial in the way that a lot of things at Princeton were beneficial: You don’t realize the full benefit at the time. As I accrued experience, I would look back on many things — the distribution requirements and the experiences that I had — as giving me a perspective that I’ve come to appreciate more fully.”

Sam Rosen ’65

Thesis: Friendly Competitor or Deadly Rival: The Feeling in England Towards Germany at the Outbreak of the First World War (History)

“I really don’t know how I came up with the topic. I didn’t know enough French to do any research in French, so it had to be English. I must have read something at the time that made me wonder about the feeling in Britain towards Germany at the outbreak of World War I. It may have been The Guns of August.”

Self-grading: “Some of it was just so vague. In trying to make a point, I really didn’t understand what I was trying to say. … I was surprised at the detail that I had gone into and the depth of research that I had done. I was looking at steel manufacturing statistics in England and Germany in 1912. Really? I knew how to find something like that back then, before there was Google? … I was really flabbergasted.”

Research Memories: “In my carrel on level C of Firestone, there were stacks and stacks of books. I would leave the library at quarter to 12 — it closed at 12 — every single night, it seemed. … The two junior papers that we had to write helped. I’m not sure that I would have been able to tackle the thesis without having those two under my belt. They sort of built the base.”

Lessons Learned: “I have retained an interest in World War I, and the genesis of that [is] whatever led to writing that thesis and the thesis itself. I’ve spent 50 years trying to understand a few aspects of World War I. Some of them I touched on in my thesis, but having re-read it, I still don’t have the answers. Maybe walking around the battlefields will allow me to gain that insight.” (Rosen spoke to PAW days before he departed on a trip to visit World War I battlefields in Belgium and France.)

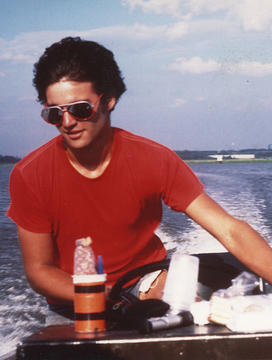

Joe Ryan ’83

Thesis: Nutrient Behavior in the Raritan River Estuary (Geological Engineering)

Self-grading: “I’ve had a lot of experience reading theses since then [as a professor at the University of Colorado], mostly master’s and Ph.D. theses. And I felt like I got such good training that [my Princeton thesis] looks really good to me. It’s well written. And all I can think is it must have been very carefully reviewed and the standards at Princeton were high. It just reminded me of how important it was in where I’ve ended up.”

Research Memories: “I, along with a couple other undergrads, had a little office in the basement of Guyot Hall, where there were three desks and then the whole rest of the room was filled with fossils and rocks on shelves. It was kind of spooky sometimes, but it lent to a good feeling that everyone was working really hard on their theses and putting a lot of effort into it.”

Lessons Learned: “Over the years, I’ve noticed that there are a lot of A-students who have a hard time with research. Sometimes it’s the B- or C-students who are a little better at it because they find that it’s something they can do well if they put the time in, whereas the A-students are maybe a little too used to everything being perfect. When you’re out in the field and in the lab, nothing’s perfect. … If you’re not failing, it’s not research.”

Sarah Sakha ’18

Thesis: Trump-Effekten: Sweden’s Integration of Iranian Migrants as a Case Study for the United States (Woodrow Wilson School)

“Toronto and Stockholm have two of the largest populations of Iranian immigrants and refugees. I narrowed it down to Sweden ultimately because not much research had been done on that part of the world … and [in the summer of 2017], I thought it was a great time, politically, to engage with these issues.”

Self-grading: “It was 110 pages — I didn’t realize I had that much to say. It was personal but also professional, to look back on my four years [at Princeton] and realize this is the product of all my education. … I think it was just an exciting and happy experience.”

Research Memories: “I [spoke with] practitioners and policymakers … but then I also had 27 interviews with Iranian immigrants and refugees, with a wide variety of ages, reasons for migration, gender, [and] educational and occupational backgrounds. … That was the biggest thing I’ve carried with me — being able to use my language and identity to connect with them. People trust you more if you can relate and speak to them in their mother tongue.”

Lessons Learned: “Don’t give up. There might be departmental or administrative pushback. If the person you go to [first] doesn’t give you funding, go to your minor, go to other departments, because there is funding at Princeton. You just have to go search for it.”

Jim Sandler ’57

Thesis: The Role of the Federal Government in the Development of the Nuclear Power Industry: the Regulatory Function (Politics)

“The premise of the thesis was that atomic energy was unique because it was developed as a government monopoly through military use. And it was a struggle to allow for the deregulation and declassification of information to permit the private sector to enter into industrial development of nuclear power and even for medical applications.”

Self-grading: “I felt, frankly, surprised that it was as accomplished as I think it is now, in terms of the organization, the research, the support, and documentation of my findings. I guess it’s a great tribute to the value of a Princeton education. I came out of a public high school in the Bronx and I produced a document, four years later, which I think holds up pretty well — and has relevance.”

Research Memories: “I spent a great deal of time in Washington, and I had access to officials in the Atomic Energy Commission and Congressional authorities. … It was really pretty elevating. I obviously had help getting access, but looking back, it was quite an adventure.”

Lessons Learned: “In law school, I maintained that interest in administrative law, which I think was born of the thesis experience. I’ve had a practice that has involved a significant amount of public-sector work, and I was chairman of the Connecticut energy advisory board for almost 20 years.”

John Schachter ’86

Thesis: Smokescreen: The Tobacco Industry and the Media (Politics)

“In April of ’84, I was reading the Washington Monthly and there was an article about the power of the tobacco industry, and it just grabbed my attention. … I decided not long after that this was a topic I wanted to really delve into.”

Self-grading: “It was pre-spell-check, so I found an alarming number of typos I wish I had caught before submitting it. I was pretty arrogant in the thesis — and I had that problem through a lot of my time in college, where my papers were making more bold assertions of fact that were more opinion. … But 33 years later, I was on-message for arguments [that are still relevant].”

Research Memories: “I was looking at things like Time magazine, Newsweek, and U.S. News & World Report, which were the three big news magazines at the time. Tobacco money was usually their biggest source of advertising dollars, and they almost never did an article about the dangers of smoking.”

Lessons Learned: “Choose a topic you’re passionate about and jump into it fully because it really is a great experience — and largely a once-in-a-lifetime experience. … About five years ago, I started working at the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. It took me a little while to get there, but I ended up back where I started.”

Greg Schwed ’73

Thesis: Rebelling Along Traditional Lines: The Fiction of John Barth (English)

“My thesis was a critical exploration of the works of John Barth. It was an attempt to analyze how the author, despite making the reader intensely aware of fiction’s artifice, is still able to speak to the reader’s heart and mind.”

Self-grading: “Going through my thesis, I would see some words and think, ‘You really were showing off a little bit there.’ It's always a little embarrassing to see the pseudo-scholarly cliché stuff. One of the things that's hardest to learn as you mature as a writer is making your writing simpler. And that includes writing for law — you never know how much a judge knows about the topic, let alone the clerks of the judge. Making it very simple and unencumbered with big words is a good thing to do.”

Research Memories: “It was a wonderful time — I had my carrel in Firestone Library, and from January until the deadline, I just put my head down and charged. I had a very nice girlfriend who was a class year behind me and who was understanding about this and actually read some of my work and helped me type, back when people had typewriters. It was hard work, but it was hard work that I was into doing.”

Lessons Learned: “As a lawyer and a litigator, I ended up in a profession where writing is important. We went into battle in litigation armed only with words, so knowing how to use them was pretty important. And my thesis was an important piece of confidence-building. I learned I could write an extended argument and it would work.”

Bob Sellery ’60

Thesis: Expatriate Writers: Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Dos Passos (History)

“I had taken a course in the English department about modern American and British authors, and the person who taught that, Professor John William Ward, was coming over to the history department the fall of my senior year. I wanted to use Hemingway and Fitzgerald novels to write about their impressions of World War I and post-war society in the 1920s. [Ward] suggested one more author, John Dos Passos.”

Self-grading: “My writing was pretty bad then. … The balance to that was that Professor Ward wrote at the end, ‘I was impressed by your growing seriousness and sense of responsibility.’ ”

Research Memories: “There were a lot of commentaries about those three authors, and Professor Ward, being an English professor, knew them all. So he gave me quite a list. … That was a growing experience, to be introduced to the literary commentators of the time — Van Wyck Brooks, Richard Blackmur, Malcolm Cowley [and others].”

Lessons Learned: “It was an outstanding independent research and writing experience. It started out as something that I didn’t know whether or not I could complete, and it was satisfying to have completed it. … The net-net is that I’m not overwhelmed now by large or complex projects.”

Melissa Stuckey ’00

Thesis: Migrant Children in Washington, D.C. (History)

“My thesis examined the lives of the children of the Great Migration generation … some of the most marginalized children. [They were] very poor African American kids who moved with their parents from the rural south to Washington, D.C.”

Self-grading: “The thing that struck me is how earnest I was and how difficult the story that I was trying to tell was. It is not a senior thesis that I would recommend to my 21-year-old self to take on. It’s really challenging work when you’re thinking about primary sources, and needing a lot of strong primary sources. To write a history about children … whose parents have limited education. And the children are just children so there aren't voluminous documents. But it’s a really important story, and I did my best.”

Research Memories: “I had to travel not to just one archive in Washington, D.C. — I was going to several places to find scraps of material to be able to tell the story of these young people in the 1900s. Just being able to pull together a cohesive story from those bits and pieces from the many primary sources — that was quite a feat.

“And this was before we were smart about backing up our work in certain ways. I just remember thinking, ‘If Butler catches on fire, I am going to throw, as far as I can, all of my documents out of the window.’ Not logical, but I certainly had a fire plan.”

Lessons Learned: “Research is really hard, and you can’t do it alone. Everyone from my thesis adviser Nell [Irvin] Painter to the archivists at the National Archive and the Library of Congress — all of them played a really important role in helping me to get what I needed and to get where I needed to be. There is no ‘I did a thesis by myself.’ You can’t do this alone.”

Kathy Taylor ’74

Thesis: Geoffrey of Monmouth and Sir Thomas Malory: Two Aspects of the Arthurian Legend (English)

“I started right at the beginning, from when the Arthurian legend started in England, and continued to the end of the Middle Ages. … The language and how Arthur was presented was very reflective of the times when the pieces were written. Arthur is the once and future king, of course, because the Arthurian legend never died.”

Self-grading: “I was expecting to kind of cringe, but in fact, I was surprised at how grown-up it was. I guess now that I’m ‘old,’ I think of a 21-year-old as being a kid. I was pleasantly surprised at how well I wrote it — not to say it was elegant in any way. But it sounded like something a grown-up wrote, not something a kid wrote.”

Research Memories: “I loved every minute of working on my thesis. … I was in one of those old, metal double-carrels on B-floor, and it was right outside the Scribner Room, which was kind of the English department room [at Firestone]. … I had my creaky shelves, and I’d turn on my little light. I loved being in my carrel and loved being able to walk out of my carrel and walk into the Scribner Room. It was my quintessential student experience at Princeton.”

Lessons Learned: “I think it’s the first thing —and in my life, the only thing — I did not procrastinate on. I am a world-class procrastinator, even to this day. … You’d think I would have learned, ‘Oh, it doesn’t have to be stressful!’ Because I loved doing it so much, I didn’t worry about spending hours and hours on it.”

Nancy Herkness Theodorou ’79

Thesis: The High Dive (English, Creative Writing)

“At the time, you had to apply to write a creative thesis, and you had to have been in the creative writing department for, I think, six semesters. … I wrote poetry. We could use poems that we had been working on through our entire time in the creative-writing program, but they had to be revised and strengthened. And we were also required to write a 15-page introduction about what influenced us as we were writing.”

Self-grading: “Reading back through it, I was amazed how well it stood up. It’s young-person’s poetry — the point of view is that of a college student — but except for one poem, they really stand the test of time. I was pleasantly surprised.”

Research Memories: “My friends were all toiling away in the bowels of Firestone Library on their academic theses, and I was literally out sitting under a tree with my legal pad, revising my poems. … Writing poetry teaches you so much about writing prose. Every word, every comma has to carry weight in a poem, and that translates really well to writing prose. It keeps you writing tight and writing with purpose. It’s great training.”

Lessons Learned: “[Adviser and poet] Maxine Kumin treated me like a serious writer — I was a writer, not just a student dabbling as a writer. I learned to take criticism constructively and not personally. And I learned that the work of writing is in editing. The first draft is fun, but the rubber hits the road in the revising process. … I always had this thing in the back of my mind that I could be a writer, so when my kids went to school full-time, I sat down and wrote a novel.”

Tisha Thompson ’99

Thesis: The Trader Spy: James Magoffin and Manipulation of the Mexican War (History)

Self-grading: “I was pretty sure it was going to be full of big words and be very academic and boring, but it was better than I remember it being. I actually enjoyed reading it. It gets dry in places. It gets bogged down in me trying to show that I read all these books. But when I stick to the stuff that I was interested in — James Magoffin and the Santa Fe Trail — I think it’s interesting. I mean, this guy managed to talk his way out of a firing squad [bribing his executioners with cases of champagne]. He shipwrecked on the coast of Mexico. The ship had what they called waxworks of Washington and Napoleon, and they used those fake out the local inhabitants and ‘stand guard’ so they could sleep. This was the Wild West — it was fun stuff.”

Research Memories: “I was able to get documents that hadn’t been looked at in 150 years that were in the National Archives, under the Department of War. … Princeton also gave me $500 — I remember that was my grant — to travel the Santa Fe Trail, and as I went along, I would stop at all the different archival spots. I spent three weeks on the road for $500! … My dad went with me for half the trip, and my boyfriend/future husband went with me for the other half because nobody wanted me traveling alone for three weeks staying at the kind of hotels that I could afford.”

Lessons Learned: “I did not, at the time, know that I was going to be an investigative reporter. And looking back, I’m realizing this was my first investigative story. I really did the things that I do today — pulling primary source documents to get it straight from the source. … My thesis taught me skills that professional reporters spend a lot of money to learn how to do.”

Teri Noel Towe ’70

Thesis: Essays on the London Churches of Sir Christopher Wren (Art and Archaeology)

“I wrote my thesis on the parish churches of Sir Christopher Wren, which I had discovered on a trip to England that I made with my mother in the late summer of 1966. My initial interest was in the historical associations of certain [churches] with certain people, like Handel, for example.”

Self-grading: “I do remember that I was happy with what I’d done — not that I couldn’t have done more. But the greatest challenge of college is deciding what not to do. I’m so grateful for the things that I did, and I also remember some of the things that I didn’t do.”

Research Memories: “My carrel was on the second floor of Marquand, the library, overlooking Whig Hall. I sat there and just watched the morning of the fire. I had gone to work on finishing my thesis, and the fire department was in the last stages of dealing with that tragedy — and a tragedy it was, because Clio did not have the kind of elaborate paneling and woodwork that Whig had.”

Lessons Learned: “My musical obsession was a part of the thesis. I wrote a chapter on the pipe organs in the churches, and one of the readers said that was not really important to the thesis. And I remember thinking, ‘I guess it depends on how you look at it.’ ” (Years later, the famed organ builder Noel Mander asked Towe for a copy of the thesis, in part because he’d heard about the chapter on pipe organs.)

Fiona Vernal ’95

Thesis: Steyntje Van de Kaap: Concubinage, Racial Descent and Manumission in the Cape Colony, 1777-1822 (History)

“[The thesis] follows the legal struggle of one woman to claim freedom for herself and her four children based on the both the nonconsensual relationship she had with one of her masters as well as the consensual relationship she had with another master. Those arguing for her case tried to use very different areas of the law around consent and then concubinage to push for her freedom and her children’s freedom. She prevailed because the Privy Council in England found that the relationship she had with one of her masters was akin to marriage — and since slaves were not legally permitted to get married at that time that was the best approximation of a marriage.”

Self-grading: “I was writing to prove to my adviser [Robert Shell] that he wasn’t wrong to send me off to graduate school, and I had a really big chip on my shoulder about that. … I didn’t start off at Princeton as a good writer, so my professors mentored me and really went above and beyond the call of duty to turn me into a good writer. By the time I got to senior year, I felt like all these people had placed their faith in me, and I had to make sure they weren’t disappointed. So when I read it again, I thought, ‘Yes! This wasn’t so bad! This was actually worthy of the A that I got on the thesis from the blind readers. I would have given myself an A as well.’ ”

Research Memories: “When I saw the challenge, the first thing to come to mind was this flashback to the power outage that happened when we were writing our theses, and I think the entire senior class had a collective panic attack. … There was this whole debate about ‘Do you think they’re going to just add an extra day to the due date? Or are they going to say you should have been working on it all along?’ They did give us an extra day.”

Lessons Learned: “My adviser taught me that the research and the writing of the thesis can never be accomplished by pulling an all-nighter. Even if writing comes easy to you, you will spoil the experience if you short change yourself and try to do it in couple of weeks/days. Break your tasks into manageable pieces and plot out your thesis in the late fall and early spring, so you can have an enjoyable experience. … And so you’re not experiencing your senior year in a haze, and with stress and anxiety because this thing is hanging over your head.”

Van Wallach ’80

Thesis: An Analysis of Board-Level Union Representation (Economics)

“It’s actually a pretty progressive topic: the involvement of unions in corporate boards. That was a topic of some interest at the time. … And it’s a relevant topic today, because people are thinking about corporate governance and having diverse voices represented in corporate management.”

Self-grading: “It has a journalistic sound to it — active sentences, short sentences. It makes sense. There’s not a lot of academic jargon except when you come to a chapter on the theoretical underpinnings of board management and getting unions involved. … I was actually kind of impressed by my ability to do some sort of theoretical analysis of the topic. But it’s so far away from what my life interests were then and what they are now.”

Research Memories: “I remember going to Cornell, which has a school of labor and industrial relations — I must have taken a bus up there and did a lot of the research in their library. … And I remember being in my room and working on my IBM typewriter, this big, heavy, gray IBM electric typewriter, and just banging it out.

“On the dedication page, at the bottom, I have a five-line quote from the play Faustus, by Christopher Marlowe, which has absolutely nothing to do with my thesis. … Probably what it means is that I would rather have been writing about Christopher Marlowe.”

Lessons Learned: “Princeton made me a lifelong learner. The thesis was the capstone of what I did at Princeton, but it was by no means the end of my academic interests. … I think of the thesis as a first step in showing my ability to keep studying and learning.”

Richard Waugaman ’70

Thesis: Nietzsche and Freud: A Philosophical Comparison (Philosophy)

Self-grading: “Re-reading it, I was surprised by how much detail I went into — and surprised to find in my senior thesis ideas that are very important to me now that I’d forgotten went back so far. For example, I repeatedly said there had been some oversimplified accounts … of Nietzsche’s influence on Freud, and these are really a lot more complicated and we need to acknowledge that complexity. That really pleased me.”

Research Memories: “I took it very seriously. I may have taken it more seriously than we were supposed to. And I enjoyed all of the research that I did, mostly in primary sources by Nietzsche and Freud.

“I received excellent guidance from Professor Kaufmann. … I remember as I talked with him at one of our meetings, midway through the year, he laughed and said, ‘Listening to you is like standing under a waterfall.’ But I was very excited about the topic, and I felt very lucky to work with him.”

Lessons Learned: “Although I haven’t continued writing about philosophy, per se, I certainly continued to love academic work and research. Roughly half of my publications have been in journals of psychoanalysis and psychiatry, and nearly half now have been on Shakespeare. … Walter Kaufmann’s model and influence has helped inspire me to persevere, even when an idea is a minority opinion or controversial or unpopular.”

Sherry Wheaton Wert ’83

Thesis: What’s In a Name: The Uses of Address in the Odes of Horace (Classics)

“The Roman poet Horace addressed each poem in his four-book collection of odes to someone or something — sometimes a real person, sometimes a fictional person, sometimes a god or goddess, and sometimes even an object. I took a look at how the choice of addressee worked as a literary technique, both enhancing the meaning of each individual poem and at times subtly tying groups of poems together that a reader might not otherwise have connected.”

Self-grading: “I was pleasantly surprised at how well it was written; it just showed me that having been writing for four years, I had developed a style, and it was a really pleasant style — which, actually my thesis adviser commented on. I don’t know where that went, but at least I had it then. I was little bit like revisiting my younger self.”

Research Memories: “I was literally typing at noon on the day that my thesis was due at 5 p.m. It was funny because the earlier parts of it looked pretty clean and then we get to the last 20 pages, and there were typos out the wazoo. I had to call a friend of mine who had, annoyingly, submitted his thesis four days before, and I said, ‘Get over here! I need you to type my bibliography!’ And he ran over to Tower Club, got on another IBM Selectric, and typed my bibliography for me. So, I don’t even want to look at that.”

Lessons Learned: “My thesis is one of the things I’m proudest of in my Princeton career: Being able to just pull it out and look at it and know that I had gotten to a place where I could satisfy my intellectual curiosity in a way and to really focus on a project at that stage in my life. That was something to be proud of. You get caught up in it and panicked at the time, and often the experience isn’t appreciated fully.”

George Woodbridge ’74

Thesis: Paradeigma and Symbol in the Homeric Odyssey (Classics)

“The topic evolved from conversations with Professor [Bernard] Fenik related to literary theory — the theory of Homer having been an oral poet and what that meant for how we could analyze the Iliad or the Odyssey in a literary way. Did the fact that it was presumably composed orally … change how we can make statements about analyzing it as a work of literature?”

Self-grading: “I kind of remembered it — to the point of remembering certain phrases or sentences — but I didn’t really remember the broad sweep of the argumentation. … I think it holds up really well. I’m amazed at my 22-year-old self. It’s kind of badass, to use the vernacular, for a 22-year-old to [demonstrate] that degree of scholarship and really carry it through.”

Research Memories: “There was a certain amount of drama connected to my thesis. As it turns out, Professor Fenik was not taken with my idea, to the extent that [the dean] pulled him off the adviser role and appointed another reader. … I was proving [my thesis] in a very disciplined way — I wasn’t casting all academic discipline to the winds and freestyling it. So I really didn’t foresee the tempest. But all’s well that ends well.”

Lessons Learned: “It was like David and Goliath, I guess. I was striding into the field of battle with my little slingshot. … I thought it was a republic of letters, a democracy of intellect, so I didn’t feel intimidated by the writing and researching. As I tend to do in my life, I threw myself into it with reckless abandon, and finished it.

“I did doctoral work at the University of London, also in Greek, and I became a high-school teacher and college professor of Latin and Greek. So it was a signpost along the way toward what I spent most of my life doing.”

Interviews conducted and condensed by Brett Tomlinson, Carrie Compton, and Allie Wenner

9 Responses

Ariadne Mytelka ’17

6 Years AgoOpportunity Costs of a Mandatory Thesis

In the interest of publishing negative results (which academia too often neglects!), I submit my own experience with the senior thesis (“The Thesis Challenge: Looking Back at a Capstone Experience,” posted May 10 at PAW Online). My reviewers evaluated my thesis positively, and I have only praise for my supportive advisers. However, from the perspective of my personal and academic growth, the thesis was a dud, and my mental health suffered under the long-term stress.

The research and writing weren’t qualitatively distinct from final projects or papers I had completed previously, and I was less passionate about my thesis than about most of my upper-level classwork. Given the opportunity cost of taking fewer classes, I think my time and my advisers’ time would have been better spent if I had not been required to complete a thesis.

Based on my own experience, I would advocate for more departments to follow the example of the B.S.E. in computer science, in allowing alternate means of satisfying the degree requirements. Perhaps a reasonable substitution could be two to four additional upper-level or graduate-level departmentals. I encourage other alums, faculty, and current students to share their opinions on the value of a mandatory thesis and suggestions for alternative ways to cap off a rigorous undergraduate education.

Mark Krosse ’72

6 Years AgoGive Scholars the Autonomy They Need

I agree with Ariadne. A Princeton senior is an adult scholar who has earned the autonomy to choose their preferred means of learning and demonstrating scholarly expertise in their chosen field. It makes sense to be able to substitute two to four graduate-level seminars for a senior thesis. Substituting breadth for depth should be the scholar's choice.

Dave Fulcomer ’58

6 Years AgoThe Value of a Thesis

Until reading Ariadne Mytelka’s letter, it never entered my mind to challenge the concept of the senior thesis.

Being a public high school graduate, I struggled my first year and a half and then, in tortoiselike fashion, improved steadily through my upperclass years.

My thesis subject, the Napoleonic legend (yuck), was mercury in a bottle, and should have been challenged by my thesis adviser. It wasn’t. I spent the entire year working diligently on it, including spring break. Each chapter was submitted to my adviser on schedule. As a scholarship jock who worked in the dining halls to offset expenses, I asked my mother to type my thesis, for which I remain grateful.

When I received my grade, my adviser’s comments still ring in my ear: “Mr. Fulcomer, your title is awkward (he had approved it), the pages are not numbered, and the work is little more than a series of paraphrased quotes.” Of course he was correct, but that should have been pointed out much earlier. His “gift” to me was a 2 minus; not a bad grade, but it meant that honors had flown out the window.

As if that were not enough, I had a roommate who struggled all year with his thesis topic but had a compassionate and understanding adviser. Six weeks before the thesis was due, the topic was revised, the thesis rewritten, and he was awarded a 1 for his efforts; a lesson in reverse schadenfreude.

If given the option to pass on the thesis, I would have jumped at it.

J. Ross McGinnis ’49

6 Years AgoThe Value of a Thesis

I read with no little interest the several letters related to the value of the senior thesis (Inbox, Oct. 2 and Nov. 13).

I began reading the letters of Henry Adams in the summer preceding my senior year, worked diligently in my carrel at Firestone during my senior year (I was voted the class grind at Commencement), and wrote a thesis founded on Adams’ commentaries on American political history titled “The Sequence of Democratic Force.”

While the thesis was not the sole component of my graduating summa cum laude with a one-plus departmental grade in history, I have no doubt that it was a substantial part thereof, and I also was elected to Phi Beta Kappa, awarded the Laurence Hutton Prize, and was co-recipient of the C.O. Joline Prize in American Political History. I graduated from the Harvard Law School, wrote a book, and have been practicing law for more than 67 years.

The thesis was the summit of my Princeton years. The thesis has helped make Princeton the premier university it has become.

Robert G. McHugh ’50

6 Years AgoThe Value of a Thesis

I never questioned the senior-thesis requirement. As the deadline approached in April, I realized I’d better get started. I dropped out of rehearsals for Intime’s King Lear and spent countless hours researching in my little carrel in Firestone. My thesis subject was Kierkegaard and existentialism. I never had a faculty adviser; I never knew I could have access to one.

I did make the dash to the deadline. A few days before graduation, I was notified by the philosophy department that my thesis had been awarded its McCosh Prize. I was stunned! I still am.

Douglas B. Quine ’73

6 Years AgoThe Value of a Thesis

I believe the Princeton thesis requirement is an essential component of our unique educational experience. Original, deeply concentrated, extended study of a specific topic is very different from coursework. Princeton’s requirement provides a unique opportunity for students to experience real scholarly research. Making the thesis optional would defeat three major benefits of the program: 1) introducing unsuspecting students to the joys of research, 2) providing a collaborative experience with faculty scholars, and 3) enabling all students to have research experience to better prepare them as educated world citizens.

The senior thesis enables students to become real experts in a field (however narrow) and to understand the twists and turns that ultimately lead us to knowledge. My thesis with Professor Masakazu Konishi was my most important educational experience at Princeton and prepared me well for my Ph.D., two dozen journal articles and book chapters, 49 U.S. patents, and a fascinating career in biological research and business.

Richard A. Etlin ’69 *72 *78

6 Years AgoThe Value of a Thesis

Ariadne Mytelka ’17 (Inbox, Oct. 2) questions the value of the mandatory senior thesis. I distinctly remember thinking after finishing my third junior paper in French literature — the first that I had ever written that was 20 pages long — that next I would have to come up with a research topic for my senior thesis where I would have to write three to four such papers and that they would have to be thematically related. This was a quantum leap for my intellectual development that could not have been equaled simply by the additional coursework that she proposes as an alternative.

Ms. Mytelka labels her senior thesis a “dud.” Yet the value of a senior thesis is not circumscribed by the time frame of the senior year. An alternative outlook would recognize that this unique exercise in independent thinking and time management may well prove to be extremely useful in addressing future challenges in any profession.

Stewart A. Levin ’75

6 Years AgoThesis Challenge: What I Tell Applicants

As an volunteer alumni schools interviewer for the past decade, I provide a set of web links in advance of the interview to undergraduate class papers I wrote in physics and history as an example of what constituted A-level work, at least in my Class of '75 days. I do not post a link to my senior thesis as I do not have a copy of it. (I think I still may be able to dig up a couple of boxes of punch cards somewhere.) I do, though, relate my experience in tackling and writing that thesis. (No idea whatsoever what my junior paper was about.)

At a reunion a few years back, I did take the time to track down and reread, or at least carefully peruse, a copy in Princeton's Mudd Archives. I was, indeed, impressed at the cleverness of the mathematical applications of what are now known as "fractals" in that work. I also, from my current perspective of having written many dozens of scientific articles, cringed at the way I wrote the non-mathematical portions.

Richard Waugaman ’70

6 Years AgoA Thesis Topic?

It would ironic if a Princeton student chose this for their thesis project -- this oral history about how we feel about our thesis years later.