Seeking Wisdom? asks the brochure that accompanies every letter of acceptance Princeton sends out in the spring. That’s a tease ambitious students find hard to resist. In recent years, as many as 70 have submitted the required essay explaining why they deserve one of 45 coveted places in what is arguably the most ambitious, demanding, exhilarating course Princeton offers.

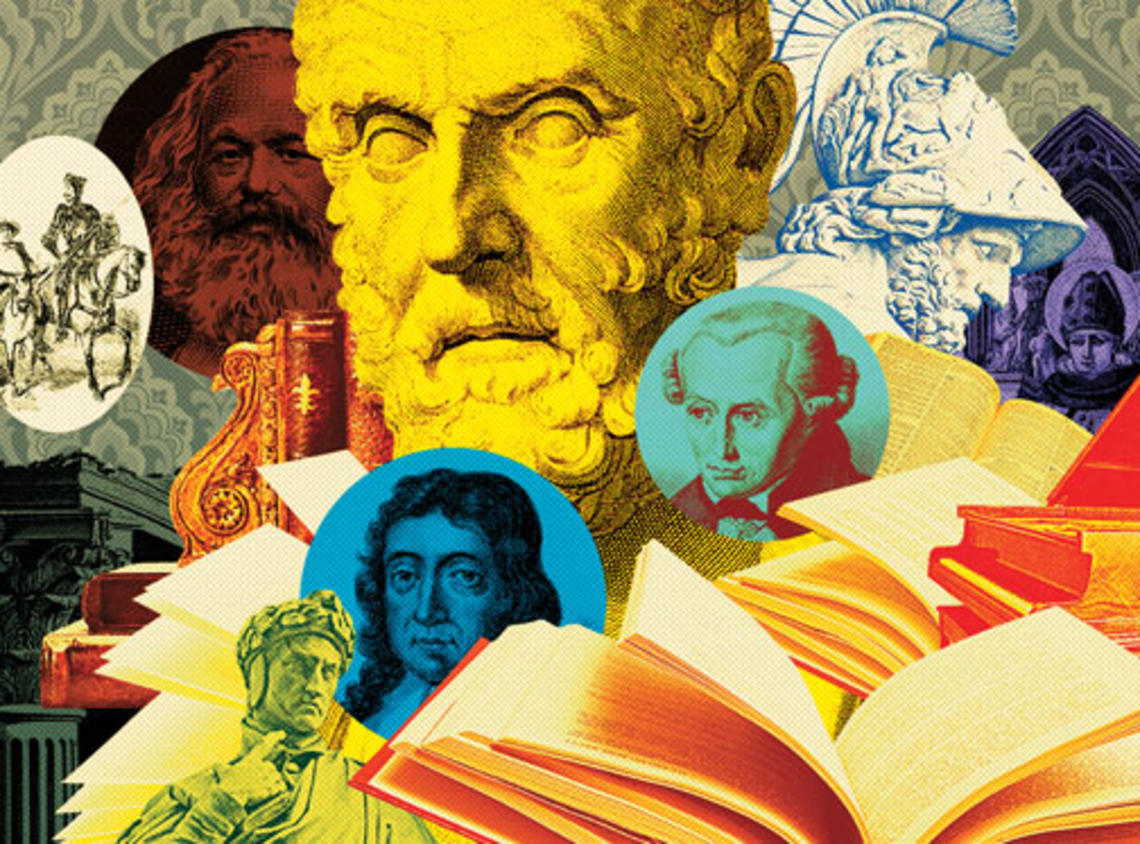

It’s Humanities 216-219, a yearlong, double-credit march through the towering giants of Western civilization. Known to the brave souls who take it as “the HUM sequence” — and to its founder, history professor emeritus Ted Rabb *61, as “intellectual boot camp” — it runs from Homer to Nietzsche, with stops along the way for just about every thinker and writer important enough to have attained one-name status: Plato, Sophocles, Augustine, Dante, Cervantes, Shakespeare, Milton, Kant, Marx, and so on. This year, in response to student demand, the course was extended into the 20th century with the addition of Humanities 220, a one-credit course that covers Freud, Joyce, Eliot, and others.

Though Rabb had to use every bit of his considerable political pull to get the sequence started, it quickly became the sort of course senior faculty clamored to teach. The 11 professors teaching the HUM sequence this year do so in the shadow of a Rushmore of recent Princeton faculty, not only Rabb but also John Wilson and John Fleming *63. “I’ve been looking forward to being part of the team for a while,” says Scott Burnham, who until recently was the head of the music department. “Selfishly speaking, it’s a thrill to hear such spectacular lectures, one after another, by some of Princeton’s top professors.”

With its high concentration of faculty and class trips to places like the Cloisters and the Metropolitan Opera — this spring to see The Magic Flute — this is a very expensive course to put on. It depends on generous gifts, these days primarily from the family of Blair Haarlow ’91 and Bill Haarlow ’89, in honor of their father, William Haarlow ’63, who loved the humanities.

Now in its 16th year, the course occupies a special place in the imaginations of Princeton students past and present. “I completely bought into the mystique that surrounded the course,” recalls Hannah Minkus ’02. “To feel that excited, that stirred, and that fundamentally animated right out of the gate in college — that’s really profound.”

Minkus had come to Princeton with plans to major in biology. The HUM sequence quickly changed that, opening her hungry mind to all sorts of exciting new possibilities. Feeling overwhelmed and at the same time inspired, she went to Professor P. Adams Sitney and asked him how long it would take her to learn Greek and Latin. Assured she could do it, she became a classics major.

Minkus says she clearly remembers “the feeling I had after those seminars that my mind was opening, my education was really starting, and that this was going to be personally revolutionary.” She is now finishing a Ph.D. in classics at the University of Chicago.

Originally, the professors wanted students to read only works in their entirety, never excerpts. That rule has been softened in response to student petitioning. So has the number of papers required, from seven each term to four. Still, not only must students attend three 50-minute lectures and two 80-minute precepts each week, but the sheer amount of assigned reading is intimidating, so great that it bulges outside the semesters.

Students are expected to arrive in September having read the Iliad and the Odyssey. And for the next nine months, the pace rarely lets up. A single week in April covers Kant, Hegel, and Marx; a few weeks later, it’s Great Expectations on Wednesday, Madame Bovary on Thursday. Ben Barron ’13 estimates that he reads perhaps 50 percent of the material carefully, skims another 40 percent, and refuses to feel guilty about skipping the rest: “I don’t think it’s physically possible [to read it all],” he says.

This raises the question of what one possibly can get out of such a speedy tour of works that, after all, have been chosen for their depth and lasting importance. (Remember Woody Allen’s line about the speed-reading course he took? “I read War and Peace in an hour. ... It was about Russia.”) A Daily Princetonian article in early February raised this complaint. Clearly, there’s a tradeoff between quantity and quality. But, as Barron points out, the four papers provide an opportunity to go into greater depth with those authors a student feels drawn to.

For Princeton, which has been trying to shake the impression among high school seniors that it is more sympathetic to math and science than to the humanities, the HUM sequence is a valuable recruiting tool. When, a few years ago, applications to the HUM sequence suddenly jumped — perhaps because of the brochure — Sitney agreed to take on a third precept, raising the number of students from 30 to 45.

Carol Rigolot, director of the humanities council, was getting more and more phone calls from students who’d been admitted to the Yale Directed Studies program. They said their choice of university hinged on whether they’d gotten into the Princeton program. While it’s impossible to know exactly what role the program played in their decision, last year 23 applicants expressed a strong interest in the HUM sequence. Of the 15 who got in, 13 came to Princeton.

This was always Rabb’s favorite course to teach, and for years, he would conclude the year with a fanciful lecture in which he imagined many of the course’s figures meeting in heaven.

Upon his retirement, in 2006, Rabb gave a final lecture, “Looking Back on the Heritage of Western Culture.” The Council of the Humanities published it in a neat little booklet. It was so successful that a HUM sequence gathering is now a popular event at Reunions, drawing far more alumni than ever took the course. “They’re being offered gold,” says Sitney. “This is the best the species has to offer.”

To request a copy of professor emeritus Ted Rabb *61’s final lecture, e-mail the Council of the Humanities at hum@princeton.edu or call 609-258-4717.

0 Responses