AS-StartingOutYuchenNew.jpg

AS-StartingOutYuchenNew.jpg

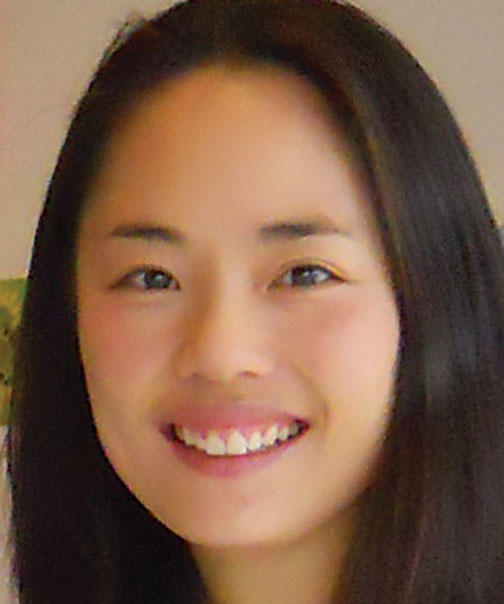

Co-founder of Pulse Café in Santa Monica, Calif. Princeton major: economics.

What she does: Zhang serves customers, orders inventory, works with wholesalers, hires employees, and manages marketing. “Just like a startup, you have to do everything,” says Zhang, who left a job in management consulting in New York to open the café with her mother in December. On the menu: hot and cold smoothies; “energy bowls” (warm salads high in protein with ingredients like quinoa, black beans, and buckwheat noodles); boba (a drink with tapioca pearls at the bottom); and an assortment of home-brewed non-dairy milks.

What she likes: “I find myself more challenged,” she says, “and using my brain more than in any other job I’ve ever held.”

Challenges: “To get people to understand what your product is and why it is good. ... [And] always trying to bring something new and to never bore people.”

Book Club.

Join and Read With Us.