Crashing the Conservative Party

Princeton has been an incubator of right-wing talent over the past 60 years, yet students and alumni say conservative life on campus is endangered

A Parable

In May 2022, at a Reunions panel on “The Fight For Free Speech at Princeton and Beyond,” Princeton’s McCormick Professor of Jurisprudence, Robert “Robby” George, shared this parable:

“I arrived at Princeton way back in the Middle Ages, in the fall of 1985. And [back then], there were some faculty members who were known to relish the prospect of a certain kind of student coming in.

“They had a real reputation for it — they’d be rubbing their hands together [in anticipation] of a student coming in from the cornfields of Indiana: Eagle Scout. Grandpa was a World War II veteran. Saluted the flag. Patriotic spirit. Evangelical Christian. Traditional morality.

“And they couldn’t wait. Because they were going to get him here, and they were going to tell him about Darwin, and the historical criticism of the Bible, and so forth. Challenge him — challenge him!

“We don’t get that student anymore. These poor people, these faculty members who might like to [challenge him], they don’t get the opportunity. Because the kids come in pre-indoctrinated. So they’ll come in from Nightingale-Bamford, Andover, Exeter. Or from these famous public high schools.

“And they are just, you know, fully in line with — totally on board with — can give you chapter and verse as if it’s the catechism of — the whole ‘woke’ program: environmentalism, racial issues, sexual issues, and so forth.

“And they arrive.

“And this time, I’m the one.”

Two Stories

There are two stories that can be told about the conservative project at Princeton.

The first is that it has been wildly successful. Over the past 60 years — ever since the modern conservative movement rose from the ashes of Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential bid — Princeton has become a premier incubator for right-wing talent.

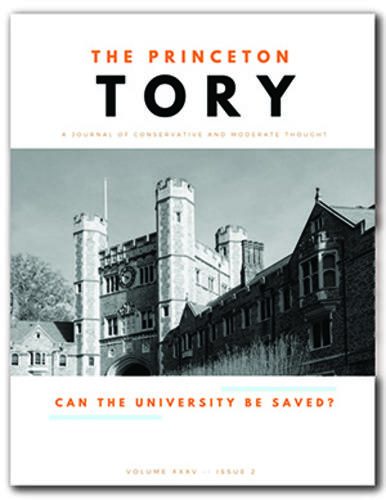

During this era, Old Nassau has minted generations of future conservative lawyers, judges, politicians, bureaucrats, and intellectuals. In June, when Supreme Court Associate Justice Samuel Alito ’72 wrote the majority opinion in the Dobbs v. Jackson abortion case, he set a new high-water mark for Princetonians’ contributions to the conservative cause.

This same period has also seen the rise of several lasting conservative institutions on campus. The Princeton Tory magazine, founded in 1984, is one example. The Anscombe Society is another. Since 2005, it has promoted a socially conservative stance on marriage, family, and sexual ethics.

Then there is the James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions, which sits under Princeton’s politics department. Under the stewardship of Robby George, it has become a training ground for young legal minds, especially through its popular undergraduate fellowship program.

And after 30 years on campus, it’s fair to say that George, too, has become an institution unto himself.

“Robby cares a lot about undergrads. You know, he could be a teacher at any law school in the country, but he chooses to be at a university without a law school,” said Solveig Gold ’17, a postdoctorate researcher at the James Madison Program who also worked with George when she was an undergraduate.

“Robby also, I think, loves Princeton as an institution. Though some of us are increasingly skeptical that his love for the institution is justified ... . Although I say that while, of course, still loving the University, too.”

Which brings us to our second story. This is, for what it’s worth, the story that is being told by many politically conservative alumni themselves: that conservative life at Princeton is embattled, endangered, and maybe even dying.

Late last year, I spent many hours talking to conservative writers, professors, think-tank executives, attorneys, television hosts, business owners, and government officials. Time and again, I ran into what I came to think of as “the moment.” This was when my interviewee would break away from their (usually fond) reminisces about the Princeton of yore — and utter, instead, some dark assessment about the Princeton of today.

They wanted to know: Had I heard … ?

Had I heard … about the new threats to free speech on campus? About how the University had, for instance, approved no contact orders that barred writers from The Princeton Tory from contacting liberal student activists — thus blocking journalistic inquiry on campus?

Had I heard … about how official Princeton institutions were abandoning their standards of political neutrality? Had I seen the statement from the University’s Gender + Sexuality Resource Center that had openly condemned the Supreme Court’s decision in the Dobbs case?

Had I heard … about what they did to Joshua Katz? (This was the most frequently referenced incident in my interviews. Here’s some background: Katz was suspended in 2018 for having a relationship with a student in the mid-2000s, and then fired in 2022 because of new evidence about his conduct during the relationship, according to the University. His supporters, including Gold, Katz’s wife, say that Katz was dismissed for a different reason: because he described a defunct student group called the Black Justice League a “small local terrorist organization” in a 2020 opinion column.)

“We are excluded, explicitly, and with malice,” Sev Onyshkevych ’83 wrote when I asked if he had time to talk for this project. “[F]or students, it is much more difficult to be an ‘out’ conservative than it was to be Jewish, Black, female, or gay in my day. So much for ‘diversity’ of viewpoints, nor tolerance, nor inclusiveness.”

16 Polls

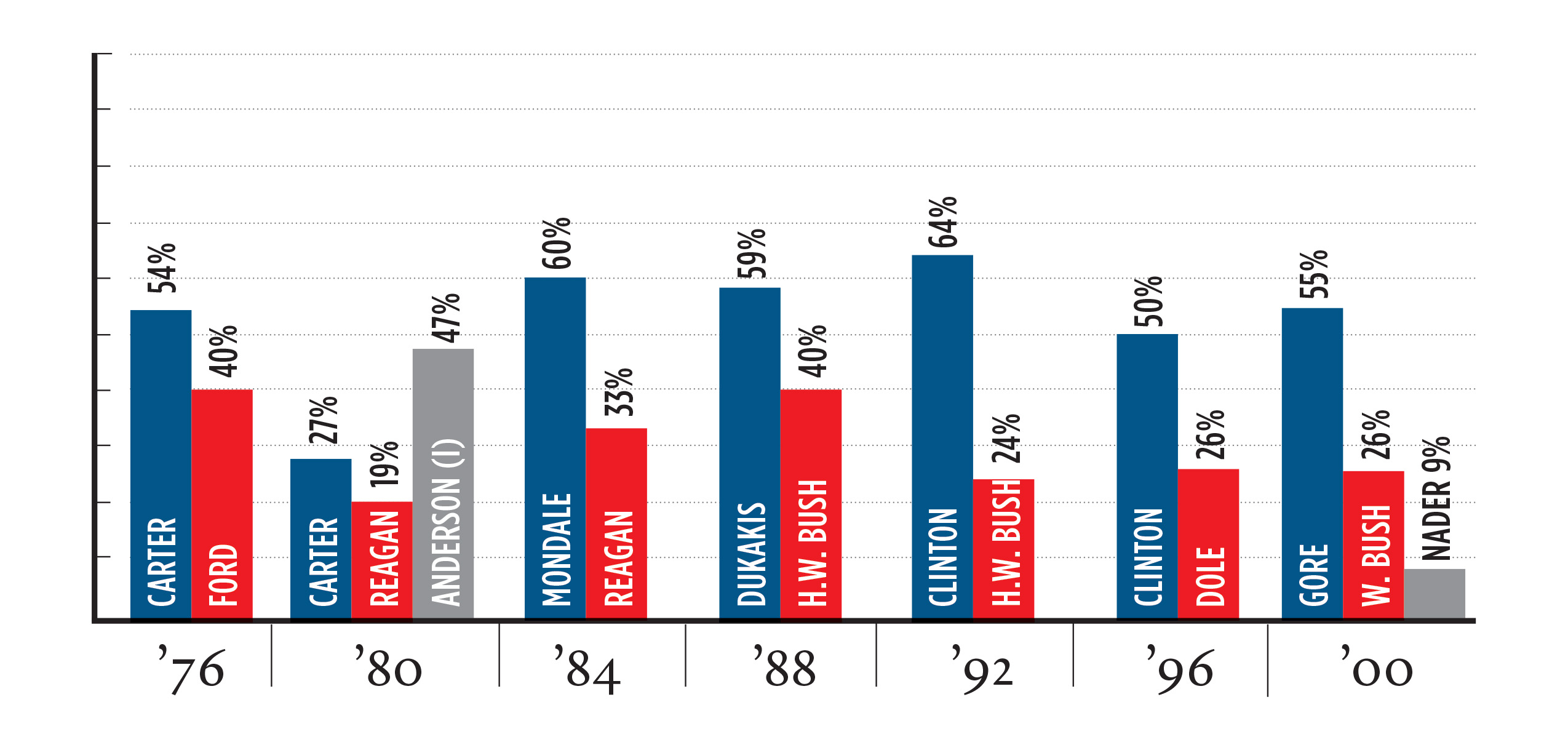

Is Princeton no longer a politically conservative campus? Was it ever? Here is a tale of 16 election polls:

In 1952, as was its custom, The Daily Princetonian surveyed its readership about the upcoming presidential election. It found that 72% of undergraduates favored the Republican, Dwight D. Eisenhower. A mere 27% went for the Democrat, even though he was one of Princeton’s own: Adlai Stevenson 1922.

Four years later, Eisenhower won the Princeton vote once again, by a similar margin, against the same opponent.

The next presidential election cycle, in 1960, offered a fresher matchup: Vice President Richard Nixon on the right, versus the young John F. Kennedy on the left. Still, the result was the same: nearly 70% of the undergraduates supported the Republican.

But then, in 1964, a reversal: Lyndon Johnson 66%, Barry Goldwater 27%. For the first time since on-campus polling began in 1916, a Democrat had won the campus vote.

And then, again, in 1968, it was: Humphrey 40%, Nixon 28%.

From then on, the trend was clear:

Around two-thirds of the way through the 20th century, it seems, the political makeup of Princeton’s student body began to veer leftward. At the same time, Princeton’s cultural reputation for being a staid, aristocratic, conservative place hasn’t changed nearly so much.

This divergence between politics and culture explains why the concept of the Princeton conservative remains so slippery. It’s why it might have been possible, for instance, for a politically liberal student in the 2010s to talk about the difficulties of coming up as a queer artist “at a conservative place like Princeton,” while, at the same time, their politically conservative classmate could lament their existence as a dwindling minority.

Neither student would be wrong, exactly.

Four Conservatisms

Princeton conservatism is, in reality, Princeton conservatisms — plural.

Princeton’s traditionalist reputation has never depended solely, or even mainly, on its ties to the conservative political movement — which is to say, on its reputation for political conservatism.

That’s because there are plenty of other conservatisms that make Princeton, Princeton: ways the school tends to resist change.

First, there’s the school’s academic conservatism. You’ll find this in Princeton’s ongoing commitment to pure research and the senior thesis; and in its fealty to the (ironically named) “classical liberal arts.”

There is also Princeton’s 2015 adoption of University of Chicago Free Speech Principles. In theory, these have kept Princeton on the outside of progressive philosophies that balance free speech guarantees against a desire to protect people against harmful or dangerous speech.

Next is Princeton’s aesthetic conservatism. This one is the easiest to picture. You’ll find it in the school’s commitment to preserving its Gothic campus core. And in the “WASP cosplay” cheerfully donned by students of all backgrounds at Lawnparties, or on plenty of other school days.

And then, there’s what might be understood as a kind of conservatism of the elite. This is the conservatism by which Princeton serves as a bastion of the old, still-dominant social order. Big Business … Big Finance … High Culture … the Ivy League.

Yes, Princeton now has more racial diversity than it used to, as well as improved financial aid. But through it all, Princeton has remained unshakably committed to defending its existence as an elite, private university. That’s conservative!

“Before the 1960s, elite universities were schools that catered to the children of local wealthy groups. After, the purpose of Princeton has been to find the best, most energetic, most achievement-oriented, most talented young people from all over the country, and vacuum them up. It cuts them off from their local roots, and then they don’t go back.”

— Yoram Hazony ’86

Unity

By and large, Princeton’s conservatisms have tended to coexist peacefully, or even commingle.

When I was on campus in the early 2010s, I was particularly fascinated by a well-dressed subset of Princeton’s right-wingers — young traditionalists who seemed to unite the school’s various conservative traditions in their very personhood and bearing.

Academically, I remember these men and women as being terrifically well-prepared in precepts. Aesthetically, they stood out for their commitment to midcentury collegiate style. Think sweater vests, blazers, and bow ties — not always all at once, and not all the time, but certainly for special occasions.

And if that sounds a bit like a caricature, remember that sartorial self-parody is itself one of Princeton’s greatest traditions. (See also: Lawnparties, beer jackets, “the Ivy League Look.”) I have also checked these recollections against my generation’s archive of record, the Facebook album. And there they are: my conservative friends and acquaintances, those Princeton Tories, wearing natty suits, sipping dark spirits, and chomping on fat cigars.

Disunity

These days, however, the threads that once bound Princeton’s various conservatisms together have begun to fray. And even in Princeton conservatives’ own telling, this unraveling isn’t solely the fault of the “woke left.”

Consider how the populist wing of the Republican Party has gained in strength over the past decade — and how it has cast elite, globally minded institutions like Princeton as an enemy of their movement.

Even some Princeton graduates have broken away to join the ranks of these anti-Ivy populists — although not all of them are ready to announce it. I interviewed one Anscombe Society alum who was happy to explain their long-standing opposition to contraception and gay marriage. But they asked to move off the record before discussing their more recent awakening: that Princeton as we know it should probably not exist, because America’s “meritocracy” had become rotten to the core.

Other alumni were less shy in voicing their objections.

Yoram Hazony ’86 is a political philosopher and Princeton skeptic. In the words of Israeli newspaper Haaretz, he has also become “the house intellectual of the world’s nationalistic circles,” including the Trump White House. Conservative leaders such as Peter Thiel, Ron DeSantis, and Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban have all spoken at the “national conservatism” conferences that Hazony puts on around the world.

Hazony fears what places such as Princeton are doing to the structure of the U.S. “Before the 1960s, elite universities were schools that catered to the children of local wealthy groups. After, the purpose of Princeton has been to find the best, most energetic, most achievement-oriented, most talented young people from all over the country, and vacuum them up. It cuts them off from their local roots, and then they don’t go back.”

The Founder

Yoram Hazony ’86 is the founder of The Princeton Tory.

In 1984, Hazony and a classmate, Julia Fulton ’88, took a trip to Manhattan to ask a group called the Institute for Educational Affairs (IEA) for a year’s worth of funding. Their goal was to start a conservative journal at Princeton.

The IEA was the brainchild of the neoconservative writer Irving Kristol, who saw college journalism as a battleground for America’s youth. With Hazony and Fulton, he made a wise investment. The Princeton Tory has since published a long line of conservative notables, including Texas Sen. Ted Cruz ’92, Wall Street Journal columnist Kimberly Strassel ’94, and Fox News host Pete Hegseth ’03, to name just a few.

Today, Hazony and Fulton are married and live in Jerusalem. Fulton, who now goes by Yael Hazony, works as a think-tank executive, while her husband writes books and organizes conferences on conservatism worldwide.

Yoram Hazony’s latest book, Conservatism: A Rediscovery, also happens to function partly as memoir about the early days of The Princeton Tory. Hazony explains, for instance, that the magazine’s name was inspired by George Will *68’s 1982 book The Pursuit of Virtue and Other Tory Notions. And indeed virtue — or its absence — was a major preoccupation for Hazony in 1980s Princeton:

“There were no responsible adults anywhere. Here, 5,000 very young men and women had been dumped into dormitories together and given as much access to alcohol and drugs, sex, and party music as they could consume. And if they smashed the windows in their dorm rooms, broke empty beer bottles in the stairwells, or bashed in a streetlamp with their heads while they were drunk — all common occurrences — then nameless men in green uniforms would appear and repair the campus to its prior, Edenic beauty, with no questions asked .”

Hazony recalls making a connection between this spectacle on campus and the Enlightenment philosophers he was reading in class. “Liberalism is such a preposterous doctrine because it was devised by men who knew little about [real life]. Hobbes, Locke, Spinoza, and Kant never had children … . Enlightenment rationalism was the construction of men who had no real experience of family life, or what it takes to make it work.”

He concludes: “The freedom of unmarried, childless individuals — the freedom of the college campus — is not something that real-life families, communities, and nations can have.”

The Rebel

If Yoram Hazony is The Tory’s father figure, Matt Schmitz ’08 is one of its rebellious children.

In college, Schmitz wrote for, edited, and served as publisher of The Tory. From its pages, Schmitz probed what he saw as the hypocrisies and failures of Old Nassau’s dominant liberal order.

Today, Schmitz is a founding editor of the political journal Compact Magazine. Since its debut in 2022, Compact has published a heterodox slate of religious conservatives, anti-interventionist foreign policy wonks, and supporters of social-democratic economic programs. The notion that these traditions can (and should) reunite has led Schmitz to support Donald Trump’s 2024 presidential reelection bid.

Schmitz tells PAW he is “depressed” by what he sees as the Princeton administration’s indifference toward freedom of speech and due process. And in 2020, he wrote this critique of higher education more generally:

“America is undergoing a godless revival. A new creed — called ‘social justice,’ ‘wokeism,’ or ‘the successor ideology’ — resembling religion yet avowedly secular and anti-spiritual, is spreading across the country. Its seminaries are the nation’s elite universities, its missionaries work in prestigious newsrooms.”

When he’s not in high-prophetic mode, Schmitz is also a keen observer of the tribes to which he has belonged. These include Nebraskan churchgoers, Catholic intellectuals … and Princeton Tories.

At Princeton, Schmitz says, “I was never much of a scotch-and-cigars guy, myself. But yeah, there was some of that, and I think it’s an interesting thing. You know, that notion that, like, young conservatives would drink scotch and smoke cigars together.

“Being kind of ‘young fogies’ [together] — that’s interesting. I guess it’s the well-established type. And it brings out the ironies of being a rebel for the sake of order. The provocateur, in favor of conformity.

“I mean, how does that really work? In what sense can you really be conservative, or be traditional, when you’re publicly in rebellion against the institution that embodies order and authority in American life?

“Nothing embodies order and authority in America like Harvard, Yale, and Princeton. These are the institutional continuations of ‘White Anglo Saxon Protestant’ rule in the country, right? Of, quite literally, clerical authority.

“So it’s very funny to kind of say, ‘Well, I really support order, I really support authority. I reject chaos. And that’s why I’m rebelling against Princeton University.’ ”

The Justice

Here’s a question I kept asking alumni: How much credit does Princeton University deserve for the success of its most prominent conservative graduates?

“You know, Sam Alito ’72 is a Princeton alumnus,” begins Jerry Raymond ’73. Raymond is a businessman, attorney, and member of the board of directors of The National Review. He is also a former schoolmate of Alito.

Raymond continues: “But I don’t think there’s a design to it. I’d like to think that if you gather together a group of above-average young people, some percentage of them are going to turn out to be conservative and libertarian, right?”

Raymond and Alito attended Princeton at a tumultuous time. Antiwar undergraduates burned their draft cards, firebombed ROTC headquarters, and boycotted the P-rade.

At the same time, some conservative students held rallies and teach-ins in support of U.S. military action in Vietnam. They did so, primarily, as part of a group called Undergraduates for a Stable America, or USA.

One of USA’s biggest successes was a referendum it sponsored on the future of the school’s ROTC program. Princeton’s faculty and trustees had been planning to kick ROTC completely off campus, but when the student body voted in favor of keeping the program, the administration reversed its decision.

“We were able to kind of act as a conscience when there were excesses that were antithetical to what a university should be,” says Raymond, who served as chairman of USA during his time at school.

Alito, meanwhile, was friends with USA members — one was even his commander in ROTC. But he did not participate in any of its campaigns; in fact, he steered clear of all campus groups that might be read as political, let alone conservative.

But as PAW writer Mark F. Bernstein ’83 described in his 2006 profile of the Supreme Court justice, in many other ways, Alito’s time at Princeton hewed closely to the ideal of the traditional Ivy League gentleman.

“We didn’t drink much, by the standards of Prospect Street,” [recalls Alito’s college roommate, Ken Burns ’72] , though in an affectation that might have earned him hoots of derision in down-to-earth Hamilton Township, Alito apparently had somewhat sophisticated (for an undergraduate) tastes in alcohol, shunning beer in favor of an occasional scotch, sherry, or whiskey sour. Musical tastes in their dorm room ran heavily toward classical. On weekends, Alito often would go home; friends say he regularly attended Mass. For relaxation, Burns says, “We talked with each other.”

However, Bernstein also detects a note of alienation in the Alito’s public comments about his alma mater.

“It was a time of turmoil at colleges and universities,” Alito told the Senate Judiciary Committee [in 2006]. “And I saw some very smart people and very privileged people behaving irresponsibly. And I couldn’t help making a contrast between some of the worst of what I saw on the campus, and the good sense and the decency of the people back in my own community.”

The Godfather

As for the Undergraduates for a Stable America, by the mid-’70s the group had transitioned away from overt political activism to become a self-described educational organization. “I have not noticed any … overwhelming anti-conservative sentiment [at Princeton],” USA’s chairman told The Daily Princetonian in 1976. “It’s just that there’s kind of a vacuum of conservative thought.”

Which is to say that in the history of political conservatism at Princeton, there is before Robby George, and after.

George arrived at Princeton in 1985 to work as an instructor in the politics department. From almost the moment he stepped on campus, George was a magnet for conservative students. “In the old days, there were no other fully out of the closet, truly non-hyphenated conservatives around,” he explains. Today, he is something like the godfather of the school’s modern conservative identity.

On July 4, 2000, George founded the James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions. It now boasts a $4 million annual budget, all raised by George from outside sources (although the University helps with the administrative side of its fundraising drives).

Since its founding, the Madison Program has remained scrupulously nonpartisan in its official messaging — and its undergraduate fellows represent many points along the political spectrum. But from the start, one of its main commitments has been to increase what George calls “viewpoint diversity.”

As George tells PAW, this has “enhanced the presence of conservative voices on campus.” During the school year, the Madison Program’s lectures, dinners, and research projects put students in close contact with conservative luminaries.

All of this “makes a statement that it’s OK to be conservative,” George says. “The success of the program sends a message that being open in your dissent from progressive beliefs does not mean that you’re going to be a failure in your career in academia. It sends a message that you can be conservative — or at least more toward the center, relative to progressivism — and still flourish.”

George rose to high prominence in the early 2010s as the architect of the conservative legal case against gay marriage. (Alito cited George’s work on the subject in his dissent to United States v. Windsor, which legalized gay marriage nationwide.) These days, George has gained new attention through his Twitter presence, in which he offers criticisms of abortion, gay sex, and the use of gender-fluid pronouns.

As an educator, George’s thesis advisees have included Ramesh Ponnuru ’95, the editor-in-chief of The National Review, as well as Ted Cruz. He has also provided more informal advice and support to groups such as the Anscombe Society, Princeton Pro-Life, and the Princeton Open Campus Coalition (POCC), a nonpartisan group advocating for free speech.

“One problem is that university faculty have been taught to no longer see ourselves as having a major responsibility for campus life,” George says. “And I think that’s a shame. [Student life] is not something about which we should just say, ‘Oh, the administrators, the bureaucrats will take care of that,’ — so that we can just do our research, teach our classes, and go home.”

The Alumna

Solveig Gold has known Robby George since childhood through her late grandfather, who counted him as a longtime friend. In college, she was part of a group of undergraduates who founded the POCC.

The coalition formed soon after Princeton’s Black Justice League occupied Nassau Hall in November 2015. One of the POCC’s first acts was an open letter to President Christopher Eisgruber ’83, which called for a return to “civil discussion” and warned against the dangers of “groupthink.” “Princeton needs more Peter Singers, more Cornel Wests, and more Robert Georges.”

“We denounce the notion that our basic interactions with each other should be defined by demographic traits,” the letter-writers continued. “We will not stop fighting for what we believe in.”

Some of the group’s initial meetings were held in conference rooms at the Witherspoon Institute — an off-campus, independent conservative think tank founded by George in 2003. “But this was a very student-led discussion. This was not any particular professor, you know, telling us what to do,” Gold says. “I mean, we were just motivated …. When I go into battle mode, I kind of just see red, and I do what I feel like I have to do. It’s not really an emotion. I just kind of locked in.”

Gold recently finished a Ph.D. in classics at Cambridge and now works as a postdoctoral research associate at the James Madison Program. She has been married to Joshua Katz, the former Princeton classics professor, since 2021.

Gold declined to comment on her husband’s firing. But she was frank about her feelings of disillusionment toward the University that once gave her its highest undergraduate award.

“I don’t see Princeton through rose-colored glasses anymore — or orange-colored glasses, I should say,” Gold says. “That’s a pity, because I really thought it was about as perfect as a university could be. I thought it the opposite of a hostile place to be a conservative thinker. On the contrary, I always felt supported and appreciated … . For heaven’s sake, I won the Pyne Prize as an outspoken conservative.

“And I’m really, really sad to see that none of this is the case anymore for conservative-minded students — or for any kind of differently minded student.”

The Student

Abigail Anthony ’23 is the president of the Princeton chapter of the Federalist Society, chief copy editor of The Princeton Tory, and vice president emerita of the POCC. Additionally, she is a founder of the Princeton chapter of the Network of Enlightened Women and an undergraduate fellow of the James Madison Program.

Anthony is also an inactive member of the Princeton University Ballet. That’s how she put it in a fact-checking email when listing her extracurriculars: “Dancer, Princeton University Ballet (Currently Inactive).”

If you think there’s a story there, you’re right. And you can read Anthony’s full take on it in The National Review, where Anthony also interned last summer.

Briefly, however: During the 2020-21 school year, the University’s Office of the Dean of Undergraduate Students (ODUS) hosted a series of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) workshops for leaders of undergraduate arts groups. The goal of this “EDI circuit” was to “center equity, diversity, inclusion, and anti-racism in Princeton’s arts community.”

Following the end of the program, several groups, including Princeton University Ballet, presented “anti-racism action plans” at an ODUS-sponsored EDI event. The Ballet’s plan began: “Ballet is rooted in white supremacy and perfectionism. We are all entering this space with a mindset that what we see as perfect is a white standard. Unlearning that will be difficult, but rewarding[.]”

Before Princeton, Anthony attended a performing arts boarding school in Philadelphia where she danced 40 hours a week while taking online classes at night. In her opinion, “The Princeton University Ballet is not a ballet club. It is a social justice activism group.”

“I would not entirely disregard anti-racism,” Anthony says. But, she adds: “If you can’t escape politics within a ballet club, if you can’t simply perform as a butterfly in Carnival of the Animals without being indoctrinated with anti-racism initiatives, then there’s no space on campus without progressivism. It’s totally absurd!”

(Princeton University Ballet declined to comment for this story.)

“I don’t necessarily like Princeton, but I am glad I went here. I think that, of the elite schools in the United States, it is one of the most sympathetic and welcoming to conservative views. With all that said, it hasn’t been particularly enjoyable. Peers I have never met have taken to social media to call me transphobic, racist, fatphobic, an enemy of queer people.

“There can be extreme loneliness [at times], even though we do have a relatively thriving conservative community. We have issue-based organizations like Princeton Pro-Life and Anscombe, and then we have broader conservative organizations like The Tory, and Clio, and the Federalist Society. And so it is easy to find a conservative community on campus. But associating yourself with that community will subject you to criticism, and even hostility, from your other, more liberal peers.”

The Professor

Three of Abigail Anthony’s eight semesters as a college student have taken place during pandemic years in which Princeton students took most of their classes on the internet and were forbidden from large social gatherings.

This digital interregnum may explain the current discontent of the Princeton conservative, says politics department professor Keith Whittington, who studies free speech and academic freedom in higher education.

COVID-19 moved Princeton’s campus culture even more online than it already had been. This meant that, for a time, the school’s political debates were almost wholly mediated through impersonal, outrage-amplifying internet discourse.

“I can easily imagine pandemic-era technological shifts having really significant consequences for what peoples’ experiences are like as a student; how it can heighten the sense of conflict and potential ostracism and abuse that might occur,” Whittington says.

Whittington also notes that at Princeton — as at other college campuses — there have been prominent calls to rethink the impact that unfettered free speech has on racial minorities. As one Black Justice League activist put it in 2015: “It is not ‘fundamental’ to any academic setting to have ‘debates’ that make its students of color feel threatened.”

As an advocate for institutional neutrality in higher education, Whittington has tangled publicly with Eisgruber over the University’s official communications about the Katz case. But in an interview, Whittington is cautious about making definitive claims about how Princeton has changed for conservative students and faculty. He notes that perceived patterns of ostracization on campus are often hard to prove concretely or statistically.

“Just because you’re a minority on campus doesn’t, in and of itself, mean anything in terms of the [social] consequences you face for belonging to that minority group,” he says. “Presumably, there’s a small minority of students on campus from Arkansas. And yet, I can’t imagine there’s actually any kind of hostility directed towards them just because they’re from Arkansas.”

But conservatives occupy a different place at Princeton than Arkansans do, he ventures: “I think right now, we’re in a pretty heated and polarized political environment more generally. And so, I do think as a consequence, political divisions are going to be one of those areas where there might be more tension, and more unpleasant behavior directed toward that small subset of students, especially if there’s a severe political imbalance among the student population. If our larger political environment was less heated, political affiliation might not matter very much.”

The Present

Is this the last call for the Princeton conservative?

Their lives are not all strife and woe. But they occupy an increasingly strange and unsettled place within their native realm.

This is a world that, from the outside, may still look plenty conservative — but perhaps isn’t so, at least not in the ways that Tories think it ought to be.

True, they retain a high degree of influence in national politics, especially considering how their numbers have dwindled in academia and other elite cultural spheres.

But for all their successes, and the successes of their movement — including, most recently, the overturn of Roe v. Wade — the Princeton conservative feels embattled as never before.

Today, they are apt to speak in pessimistic — or even apocalyptic — tones about the future of the place they once loved. They speak of feeling outmaneuvered by a new kind of foe: a class of censorious liberals, the “wokists,” who have found a way to cloak authoritarian impulses in the language of social progress.

The Future

Of course, all of the above could also describe today’s Republican Party as a whole. Which suggests some measure of hope for the future of the conservative project at Princeton. If Princeton has, indeed, become less of a safe haven for conservative thought, and more of a combat zone for ideological warfare, perhaps that now makes Princeton an even better launching pad for tomorrow’s right-wing leaders?

It’s hardly a demerit, in today’s Republican Party, to have a track record of fighting against an icon of elite academia like Princeton. To have come of age, in other words, as a “rebel for the sake of order.”

David Walter ’11 is a journalist based in New York City.

45 Responses

Richard A. Goldman ’78

2 Years AgoStop Glorifying Professor George

I am looking forward to my 45th reunion in a few months and will enjoy seeing the remarkable changes in the student body, the beautiful campus, and hanging with my classmates and new friends I am bound to meet. I am a gay man who came out late in life. Princeton was a very closeted place when I attended almost 50 years ago. I thought that my memory might have been distorted by my personal conflicts with my sexual orientation at the time. However, after reading the oral histories of other students of my generation, I concluded that homophobia was endemic at Princeton in the mid-1970s.

Professor George and his followers would have us return to that state of repression. His “natural law” is nothing more than homophobic bigotry dressed up as high-minded theology and abstract political theory. Second class status for LGBT individuals results from application of his theory to society at large. There is nothing more natural than gay men and women living authentically, falling in love, and having a full range of human experience, including long term commitment. His cramped view of human sexuality, social order, and our political system would restrict the freedom of gay people to live in a manner consistent with their sexual orientation as an exercise of a civil right, granted and protected by our government on a pari passu basis with the rights granted to straight people. Call me closed minded and uncivil, but at this point in my life, I am intolerant of homophobic thinking and wish that Princeton stop glorifying Professor George.

I was a steady contributor to Annual Giving and participated in a number of campaigns over the years. Around a decade ago, I corresponded with the development office and informed them that I will not make any further contributions until such time as Professor George is no longer affiliated with Princeton. Don’t bother sending the letter, save the postage.

Robert Becker ’55

2 Years AgoIdeologies and the Liberal Arts Education

I lament “Crashing the Conservative Party” (January issue). As an undergraduate, I saw the aspects that Mr. Walter employs to stereotype Princeton. These did not change my life. With scholarship across the sciences and humanities, commitment of faculty to look deeply into what one did not question, humility always seeking to learn, Princeton defined education for me. I learned how what is known has failed humanity, and how what new we uncover as novel gives us hope for a better future.

The Founding Fathers were read as brilliantly flawed, struggling to resolve conflicting beliefs, victims of their times, yet somehow wise in that they framed a task for those to come. I doubt that Madison today would encourage professors to establish a “James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions.” I think Madison hangs his head in shame that all were and are not yet created equal in America, that he owned slaves and knew that others raped and murdered their slaves, that he would not reject South Carolina’s conditions and politically “die to make slaves free.” Anathema is Princeton regarded as “a premier incubator for right-wing talent” that “mints” individuals who Eric Hoffer’s The True Believer identifies as ideologues and Richard Wranghan’s The Goodness Paradox makes despots.

Walter F. Murphy’s essay “Remembering Alpheus Mason” (PAW, Dec. 1997, pp. 55-56) speaks eloquently for the liberal arts educational tradition now imperiled if not lost at Princeton. An education does not tolerate or teach ideologies, left and right, that warp, not free, young minds to think.

Kevin Raeder ’86

3 Years AgoValues in Practice

I was one of those midwestern, traditional morality, patriotic, Boy Scout youths described in “Crashing the Conservative Party” who was transformed during my years at Princeton. But it didn’t happen at the hands of scheming liberal professors or because of social pressure to conform. It was the result of experiences and conversations with fellow students.

While growing up, my family didn’t look too critically at our comfort and the history that framed it. Once I started to look at the current status of non-me people, I realized that our nation and the societies in it are quite far from the ideals expressed in the founding documents of our nation and from the description of society that dominated my youth. And the distance wasn’t an accident or something that would fix itself.

One modern conservative value and view is that there is not, and should not be, any guarantee of success, for people or ideas (especially other groups’). In the marketplace of ideas, it appears to me that conservatism is losing badly. It’s not from lack of effort or number or familiarity of ideas. It’s because of the fundamental hollowness and self-serving nature of most of them. Why should we make any special effort to preserve and amplify ideas such as these? I’ve kept most of the core values of my youth but found that conservatism is not the way to put them into practice.

M. Alexander Broadhead ’90

3 Years AgoWhat Does Conservative Mean?

I made a point of reading “Crashing the Conservative Party,” as I hoped it might have some insight into the plight of conservatives in a time when they are, nationally and internationally, in decline and retreat, beset on all sides, but especially on their right, where various authoritarian and reactionary strains of right-wing politics have largely purged them from, e.g. the Republican Party. I was greatly disappointed, then, to read an article that fails in its most basic task: to define who and what a “conservative” is.

The author notes multiple forms of Princeton “conservatism” in passing, but gives only the barest of definitions, “ways the school tends to resist change.” He then elides all left-wing movements into progressivism and/or liberalism (they aren’t the same thing, and are only a tiny part of the “left” spectrum), and seemingly defines everything on the right side of the coin as conservatism. This leads to ridiculous statements like Dobbs v. Jackson being a “high-water mark” for conservatives. (Destroying precedent and removing — for the first time in U.S. history — a Constitutionally protected right isn’t conservative; it’s radical and nihilist.) Or to holding up someone (Matt Schmitz ’08) who supports Donald Trump — a man without a conservative bone in his body — as somehow being representative of conservatives? Undermining democracy and the rule of law, as Trump consistently does, is the utter opposite of conservatism. (And before you say, “But Trump’s a social conservative,” please, please, think about who you’re talking about.)

This division of the political spectrum into two sides of a coin makes it impossible to identify conservatives on campus; to wit, the main metric for judging student attitudes is The Daily Prince’s presidential election polls. Which candidate better represents conservative values in a contest between Hillary Clinton or Joe Biden and Donald Trump? (Hint: It’s not Trump.) Corporate/Liberal Democrats have much more at stake in conserving the status quo than MAGA Republicans who are busily burning “RINOs” at the stake and scheming to start a second Civil War. I submit that there are now, just as there were in my day, plenty of centrists of all stripes at Princeton, and that it, in fact, is probably a more welcoming home for conservative ideology than the modern day GQP. (And that there continues to be a dearth of “far left” perspectives, but that’s another story.)

Mark D. Looper ’85

3 Years AgoConservatives, Republicans, and Populist Politics

I came to Princeton as a strong-defense, law-and-order, church-going, teetotaling conservative; I left Princeton as a strong-defense, law-and-order, church-going, teetotaling conservative who has never voted Republican again. The reason is that in 1983 Jerry Falwell came to speak at Alexander Hall and, not having previously paid enough attention to politics to know what to expect, I was appalled to hear the self-righteous, theocratic, anti-science views of someone so influential in the party for which I would have voted by default in 1984. Since then my estrangement has only gotten deeper as the party, with the complicity of intellectual conservatives like those profiled in the article, has become increasingly dependent on conspiracy-mongering and white-victimhood populism, leading in a straight line to Trump and his insurrection (which wasn’t even mentioned in the article). “By their fruits ye shall know them.”

As a physics major, I didn’t have time to take much more than the distribution-requirement minimum of introductory humanities courses, so I didn’t get close enough to any liberal professors to be subject to their supposed indoctrination. With regard to losing my vote, and those of an increasing fraction of my college-educated suburbanite demographic, conservatives have scuttled their own ship.

Alex Entz *20, Dallas Browning *21

3 Years AgoFreedom of Thought Under Attack

We applaud the magazine for running David Walter’s excellent article on the essentiality of conservatism to campus academic, social, aesthetic, and cultural life. As two conservatives from Iowa and Kentucky, we came to Princeton for graduate school to explore civilizational questions alongside the brightest minds in the country. Instead, our experience on campus demonstrated a waning commitment to free inquiry and a climate that was often genuinely hostile.

Take, for instance, a forum on diversity in the School of Public and International Affairs in which several students openly stated that Princeton should not have any Republican students (“Why would we want them here?”). Others suggested that Republicans could reasonably be assumed to be closet rapists given the party’s support for then-Judge Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination. The professors in charge of this forum, perhaps characteristically of the current campus environment, offered no resistance against such charges. In another instance, following a formal at Whig Hall, some students threw food at paintings of Princeton elders, chanting “take the white men down” and laughing. Classroom discussions regularly ostracized and belittled conservatives, boiling every question down to surface-level platitudes about race, gender, and climate. Unsurprisingly, campus life was often isolating and lonely, and we regularly questioned the utility of such an experience to our intellectual and professional development.

Of course, we also met students committed to free inquiry (often members of the armed forces) and a small core of able administrators, and engaged with world-class institutions like the James Madison Program. But our experience led us to worry that freedom of thought is under threat. We give kudos to Walter for showing what would be lost. And our hope is that alumni will not be so sanguine about the rise of a rigid ideology at Princeton — nor the personal hatreds that often accompany it.

Robert Edward Johnson ’79

3 Years AgoWhy Are Conservative Undergrads in Decline?

“Crashing the Conservative Party” in January 2023 PAW quantified a decline in Princeton students admitting to The Daily Princetonian they were voting Republican. Just as City Hall Republican voters in Chicago may be shy on polling (if they want to keep their jobs), I suspect the decline has a similar explanation. The percent of undergrads getting financial aid has risen sharply since the 1970s, and given how expensive it would be to pay for Princeton out-of-pocket now versus the 1970s it’s possible lots of students saying they’ll vote Democrat are lying, or perhaps the “missing” students not responding to the poll are GOP. If I were afraid of losing financial aid and not being able to graduate, and suspected that “cancel the non-woke” types on The Daily Princetonian might “out” me, I’d be a shy Republican too.

Another possibility is lots of non-left students avoid Princeton and go to places like the University of Chicago (ranked number one out of slightly over 200 institutions on free speech compared to Princeton’s abysmal 169 and Harvard’s 170), Carnegie-Mellon, University of Rochester, and other non-Keynesian institutions, or if their emphasis is Catholicism, Notre Dame is not only more conservative than Georgetown but has surpassed Georgetown in the U.S. News rankings. An even more dismal possibility is that the application and interview process itself increasingly excludes conservatives and/or libertarians if they intend to major in a social science and admit their true beliefs.

James R. (Jim) Paulson ’72 *77

3 Years AgoConservatism and Christian Teachings

Quotations from Professor Robert George (January issue) seem to show a great disdain for evolutionary biology and biblical scholarship, suggesting that Professor George has little knowledge or understanding of those fields.

The professor also seems to sneer at those who work against racism, poverty, discrimination because of sexual orientation, and environmental degradation, slyly ridiculing them as “woke.”

In Christianity, love, compassion, and respect for people different from oneself are very important. Assuming that George is a Christian, he and other Christian conservatives should remember that being a follower of Jesus does not just mean being a member of a church. It means following Jesus’ teachings.

Norman Ravitch *62

2 Years AgoWhat Does Following Jesus Mean?

Is conservatism compatible with Christianity? What does following Jesus mean? What Jesus are you talking about? Most of these alumni, here and elsewhere, seem to have a particular Jesus in mind. But what if their Jesus is not the real Jesus?

I have studied the bible and bible scholars all my academic life and even taught a couple of classes in a sort of history of Christianity. At that time I did not yet find myself ready to discuss the real Jesus, whom I did not know, only the Jesus of the New Testament. Now retired I have no class to teach about the real Jesus; that’s why I am here.

The gospels portray Jesus in a number of ways but were written about 40 years after his death and by people who had never met him, resulting in an imaginary Jesus useful for various conversion purposes and controversies. The epistles of Paul present a Jesus Paul met only in his imagination and it was a figure hardly really human and only partially Jewish.

Scholars tell us many things about Jesus but mostly they rely on the New Testament, which is misleading. The real Jesus can only be approached from Jewish writers who can fully understand this strange Jewish man with strange Jewish ideas about God intervening in the world to save Israel primarily from its decadence and sufferings.

So here goes: Jesus preached the kingdom of God, which meant God intervening in the world, as the prophets of the Old Testament predicted, to save Israel, not the gentiles but Israel. Israel suffered under pagan rule and also the rule of Jewish renegades serving the oppressive gentile rulers wherever the Jews lived. What really motivated Jesus was how to encourage God to intervene. Everything he probably taught, as the more accurate parts of the New Testament indicated, was designed to prepare people for God’s intervention. Finally, Jesus allowed himself to get into trouble with both the Jewish temple priesthood and the Roman authorities and his predictable death would, he hoped, cause God to do his part. But God did not and Jesus died in vain: “My, God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?”

How does one follow Jesus now? A Jew would not know, a gentile would not know. No one would know. That time of knowing has passed. Thus you cannot make out of Jesus a moral teacher, all his teaching was directed at a particular purpose and was all from the Old Testament. You cannot make him a savior since God was to be the savior. What can you make of him? In my view, not much.

Barry Newberger *76

3 Years AgoEvolution and Ideology

I am rather puzzled by Professor Robert George’s parable at the introduction to the article “Crashing the Conservative Party” (January issue). I would have thought that any Princeton professor, without regard to their personal ideology, would have been teaching Darwin, not because it suited their personal beliefs, but because it was (and as far as I know, still is) the best encapsulation of the corpus of empirical evidence to which it is directed. I am not aware of any alternative, biblical or otherwise, that does the same. If Professor George does, I would be happy to hear it.

I would hope that all Princeton faculty relish the opportunity to challenge incoming students on this and all other aspects of a student’s education — and are prepared to be challenged back. That should be the case whether a professor’s ideology is “conservative” or “liberal.” Most importantly, both should be prepared to critically weigh their own views.

Jeremy Rosenthal ’15

3 Years AgoDiversity of Faculty Viewpoints

Kudos on the well-written and engaging January cover story. It’s exactly the sort of topic that could only have been covered at an editorially independent alumni magazine, and as such a reminder of how important it is PAW maintained that status.

While well and good that Princeton counts Professor Robert George among its faculty, the piece sorely lacked context around the political leanings of Princeton’s faculty writ large. Though there is (appropriately) no way to get a precise breakdown of the conservative/liberal makeup of Princeton’s faculty, researchers looking at voter registration estimate that the ratio of registered Democrats to Republicans among Princeton faculty is on the order of 30 or 40:1 (see Econ Journal Watch and the National Association of Scholars blog). While these numbers should be taken with a grain of salt, they are based on sample sizes of more than 100 and paint a picture of a vastly unbalanced faculty, out of line even with the approximately 10:1 Democrats-to-Republicans ratio among students captured in the latest Prince election poll data.

Greater diversity of viewpoints among faculty meaningfully benefits students, as Professor Keith Whittington has compellingly argued in a paper for the journal Social Philosophy and Policy. Truth-seeking — the heart of a University’s mission — is enabled through exposure to far-ranging views and an environment of healthy debate. It’s those professors with views furthest outside Princeton’s mainstream, and who are most committed to truth-seeking — Professor George and Professor Peter Singer — whose writing and talks I still find myself keeping up with. Through increasing diversity in viewpoints, political or otherwise, among its faculty, Princeton can encourage students to pursue truth and better prepare them for encountering the diverse array of views across countries and cultures beyond campus as well.

Michael Comiskey *88

3 Years AgoAn Attack on Childless People

As someone who remained a childless bachelor until age 60, I was offended but not surprised by Yoram Hazony’s ’86 ad hominem attack on childless people who, he claims, are cluelessly out of touch with real life (“Crashing the Conservative Party,” January 2023).

I grew up in a working class family of two parents and five children. We did not have a lot of money. We had a house that was too small for us. I watched my parents love, work, and sacrifice for decades. I know what a family is.

Don’t be fooled. The conservative smear against childless people is an attempt to portray conservatives as holier-than-thou while they assassinate the characters of their opponents. These pious conservatives can then suppress wages, bust unions, let corporations trash the environment, cut regulations on banks, cut safety net programs and, above all, cut taxes for the rich while passing the resulting debt onto the middle and working classes.

All of which are anti-family.

Irfan Khawaja ’91

3 Years AgoOn Parenthood and Doctrine

In his comments to PAW, Yoram Hazony ’86 describes liberalism as “a preposterous doctrine because it was devised by men who knew little about [real life]. Hobbes, Locke, Spinoza, and Kant never had children ….”

Well, Jesus Christ, St. Thomas Aquinas, and the adherent popes, cardinals, bishops, priests, and nuns of Roman Catholicism “never had children,” either. One inference we could draw is that like liberalism, Christianity is a preposterous doctrine devised by men who knew little about real life. Another is that a person can have children but lack even a minimal sense of intellectual responsibility. Such a person might well say whatever played to the peanut gallery of the moment, regardless of the fallacies it expressed, and regardless of its connection to reality.

As a former editor-in-chief of The Princeton Tory amply familiar with “The Founder,” I incline toward the latter inference in this case. For present purposes, I only suggest that a choice be made between the two inferences, and I invite readers of PAW to make it.

Melissa Moschella *12

3 Years AgoRetaining a Diversity of Viewpoints

I greatly appreciated the recent article on conservatism at Princeton. While I was accepted into many equally prestigious doctoral programs (including Harvard and Columbia), I chose to pursue my doctorate in political philosophy at Princeton primarily because of Robert George. I should note that I dislike labels like “liberal” and “conservative,” because my values and commitments do not line up with those of any mainstream political party — I am, for instance, strongly opposed to both abortion and capital punishment, because I am convinced of the profound and intrinsic value of every human life. Nonetheless, as someone whose views on many controversial issues would typically be labeled conservative, I knew that I would not find many like-minded people among my fellow graduate students or professors at Princeton. Having done my undergraduate degree at Harvard, I was used to this, and have always enjoyed robust dialogue with others whose perspective differs from my own. And I generally found faculty and students at Princeton to be respectful of me and my views. Indeed, I am greatly indebted to professors Melissa Lane and Anna Stilz for agreeing to be on my dissertation committee (along with Professor George) and for providing thoughtful and constructive critical feedback on my work, which was a defense of parental rights in education. Despite disagreeing with my perspective on the topic, they were supportive of the project, and their criticisms helped me strengthen my arguments. Nonetheless, it was also crucial for my education to interact with at least some like-minded faculty and students, and this was made possible largely by Professor George and the James Madison Program, which provided needed intellectual diversity to campus and ensured that “conservative”-leaning voices would not be absent from the campus environment.

The presence of conservative voices is crucial not only to support “conservative” students like myself, but for the academic integrity of the University as a whole. As Jonathan Haidt has pointed out in The Coddling of the America Mind and other works, one of the great dangers to the contemporary university is the lack of genuine ideological diversity. Given the human tendency toward confirmation bias, the absence of voices that challenge reigning orthodoxies is sure to lead to intellectual sloppiness and a decline in academic rigor, as shown recently when several academics wrote fake articles using popular jargon that played to editors’ and reviewers’ biases, and had their work accepted by supposedly serious peer-reviewed journals in fields like gender studies (https://areomagazine.com/2018/10/02/academic-grievance-studies-and-the-corruption-of-scholarship/). Even those who completely disagree with the views of Professor George and the scholars he is able to bring to campus through the Madison Program should recognize that he is doing a great service to the University by ensuring that Princeton retains at least some degree of viewpoint diversity, and so helping to preserve it from mindless groupthink and intellectual corruption.

Editor’s note: The author is an associate professor of philosophy at the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C.

David Bonowitz ’85

3 Years AgoScotch, Seersucker, and Insurrection

I was struck by two omissions in David Walter’s “Crashing the Conservative Party.” First, how does an article that spends so much time on Princeton conservatism in the ’80s fail to even mention the Concerned Alumni of Princeton and its mouthpiece, the convicted grifter (and, naturally, Trump-pardoned) Dinesh D’Souza? Sam Alito boasted of being a CAP member. Bill Bradley had the good sense to resign from the group. If Professor George now laughs at his early liberal colleagues, where did he stand on D’Souza when he arrived on campus in 1985?

Second, how does an article that spends so much time on Princeton conservatism today not even try to put any of its subjects on the record about the Trump con, election denial, or January 6 — or their inevitable imitators among Netanyahu’s new cabinet and Bolsonaro’s thugs? Look, it’s all fun and think tanks — speech, scotch, and seersucker — until someone storms the Capitol. Where are George, Hazony, Gold, and Anthony on those conservative “successes”? At least Matt Schmitz ’08 has the guts to tell us he’s still in the tank for insurrection. What about you, Professor George? Signed up with Ron DeSantis’ thought police yet?

That said, thank you, PAW, for the helpful history lessons. I had no idea that through the ’50s, according to Yoram Hazony, Princeton mostly served wealthy New Jersey families, as opposed to being the favorite Ivy of Virginians and Carolinians. And of course I am proud to learn that no Princeton student was ever publicly drunk or indecent before 1960!

Craig Smith ’71

3 Years AgoTwo Unfortunate Conclusions

Two unfortunate conclusions emerge from your piece on conservatives at Princeton, “Crashing the Conservative Party” (January 2023). First, to nobody’s surprise, conservatism has today been solidly replaced by a deeply entrenched leftism (and we are patronizingly instructed that conservatives should gratefully welcome opportunities presented by their fortunate association with Princeton). And second, by inescapable implication, God Himself also has long since been kicked to the curb at Princeton and His position filled (properly, one is led to believe) by an omniscient and omnipotent University.

Well done, PAW!

Randal Marlin ’59

3 Years AgoA Perspective from Princeton in the 1950s

Thanks for PAW’s very interesting exploration of conservatism at Princeton since the early 1960s. My perspective is earlier, in the 1950s. Those were times when heated political debates were rare, and the phrase “silent generation” was current. So much so that a political science professor, Otto Butz, published a book called The Unsilent Generation giving voice to students’ ideas about their attitudes about life. In those days the scare of nuclear war was rampant, and bomb shelters were built. The sexual permissiveness of the 1960s had not yet arrived, in the pre-pill era.

There was of course the voice from the Aquinas Foundation, Father Hugh Halton O.P., M.A., D.Phil (Oxon) (as he styled himself in paid advertisements in The Daily Princetonian), calling on Princeton to take seriously the “Dei” part of Dei sub numine viget. This provoked a lot of discussion, sometimes heated, but whether you would call him conservative as distinct from reactionary would be open to question.

On reading about the Anscombe Society, in existence since 2005, I was curious about whether its conservatism was and is limited to family and sexual values, or whether it goes beyond that to support her, what many would see as, radical stance with regard nuclear bombs. As a young Oxford academic, Elizabeth Anscombe outspokenly and courageously opposed Oxford University’s awarding of an honorary degree to U.S. President Harry Truman, given his authorization of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Darius Gross ’24

3 Years AgoThoughtful Coverage of Campus Conservatives

As publisher of the Tory, Princeton’s journal for conservative thought, I’d like to thank David Walter ’11 for his thoughtful coverage of the state of conservatism on campus. I’m proud to study at a university where conservatives are allowed a prominent presence. Conservatism thrives at Princeton not only due to Professor Robert George’s efforts, but also thanks to the University’s adherence to the Chicago Principles, which fosters a greater degree of free expression than many other campuses in this country.

Conservative perspectives are by no means treated equally in the broader campus conversation. Still, Princeton remains a place where young conservatives can meet like-minded peers who challenge their ideas and inspire them to think more deeply. The Tory will continue to fight to keep it that way and ensure that thinkers of all stripes can engage with current events, debate, write, and evolve at Princeton.

Micah Watson *07

3 Years AgoA Grad Student Perspective

I appreciate this article for several reasons, not the least of which is that it captures well part of what I experienced at Princeton as a graduate student from 2000-07. I had the good fortune of arriving on campus the same year that the James Madison Program debuted, and while I came primarily to study with Robert George, I also sat at the proverbial feet of a host of thinkers, formally and informally, liberal, conservative, and difficult-to-classify. The Madison Program brought in a different set of fellows each year, and still does, without hewing to a narrow ideologically conservative line. And yet that infusion of fresh blood onto campus each year led to scores of intellectual feasts as there were JMP events, co-sponsored events with the University Center for Human Values, partnerships with the politics department, and opportunities of all sorts for a deeper sort of genuine pluralism that is vanishingly rare on elite campuses. “We practice what they preach,” was a mantra of the JMP, and if one peruses the archives one will certainly find plenty of conservative speakers of various stripes, but also a significant number of progressives and outright leftists.

Of course there were disappointing moments. For me perhaps the most significant marker of one understanding of “conservative” is the rather stark difference between a 1941 telegram featured in Frist reprinting President Dodds’ message to President Roosevelt immediately following Pearl Harbor “pledging unqualifiedly” Princeton’s support to the war effort on the one hand and a (then) Woodrow Wilson School sponsored panel following 9/11 at which the theme seemed to be that what happened was our fault. And of course I encountered views I found strange, even at times offensive, both in and out of the classroom.

But that’s part of why I came to Princeton: to work with the brightest minds in the world thinking and reasoning and arguing (not quarreling!) about the things that matter most. That I could do so with like-minded figures like George, Deneen, and Whittington, who didn’t think I was irrational for my religious and moral convictions, was a blessing. That I could be challenged robustly while respectfully by professors like Stephen Macedo and George Kateb was a privilege. That’s what was so exciting about studying when I was there. I could be seated next to Peter Singer listening to him challenge a pro-choice Georgetown ethicist’s reservations about abortion-as-art one evening, witnessing a debate between Jeffrey Stout and John Finnis another afternoon, and sit with a very diverse group of graduate students shooting questions rapid-fire at Justice Scalia not long after Bush v. Gore. I fervently hope Princeton has not lost the confidence it once had to play host to these robust conversations. They are desperately needed by liberals and conservatives, those of religious conviction and those of none, and all creeds and colors.

Gordon H. Hart ’70

3 Years AgoComments on ‘Crashing the Conservative Party’

With more than half a century having passed since I graduated from Princeton, I found this article to be an interesting read. For one, it is significant to see that some of the campus conservatives are women. Back in my day at Princeton, especially during my junior year, there was actually significant opposition to Princeton accepting women students, not only from alumni but also from certain (male, of course) students. What is encouraging is that today, I don’t hear of any conservative movement to return Princeton to the good old days of its being an all-male institution or students and faculty arguing that Princeton would be better today if it were still all male. It’s clearly better as a coeducational institution and that appears to widely be accepted, including amongst today’s conservatives.

Another major liberal-conservative battle line, when I was a student, was the Vietnam War. While I wouldn’t expect today’s students to refight the Vietnam War, there doesn’t seem to be any groundswell amongst conservative students and faculty to argue that the U.S. would be better off today had we “won” the Vietnam War and that the students in my day should have supported the U.S. in that war. The Vietnam War has been left to historians to explain its causes to today’s students, which is where it belongs.

It is difficult to imagine being a Princeton student today because so much has changed. Having spent 46 years married, in a monogamous relationship, to my wife, having been a regular church member for many years, and having worked for the bulk of my career in the private, for-profit sector, I suppose today I could be branded on campus as a conservative. Regardless, I think Princeton is better off today supporting LGBTQ students and maintaining affirmative action to assure a diverse student body. I’m proud to be a Princeton alumnus since the university remains one of the best in the world, if not the best, and is leading society in forging the nation’s, and the world’s, future.

Go Tiger!

Erika Davidoff Aguas ’17

3 Years AgoNo Escaping Politics

In “Crashing the Conservative Party,” Abigail Anthony ’23 bemoaned the Princeton University Ballet’s decision to draft an anti-racism action plan. “If you can’t escape politics within a ballet club, if you can’t simply perform as a butterfly in Carnival of the Animals without being indoctrinated with anti-racism initiatives,” she says, “then there’s no space on campus without progressivism. It’s absurd!” Abigail, do you know who cannot ever “simply perform”? Dancers of color. Do you think that Misty Copeland could ever “simply perform”? Every time she stepped onto a stage or a rehearsal floor, she was immediately subject to the conscious and subconscious prejudices of everyone around her, which formed invisible yet very real hurdles the likes of which you will never have to clear. There is no “escaping politics” when the subject of politics is your worth and potential as a person.

This myopic self-centeredness is perhaps the most frustrating trait shared among conservatives. They think that because the world is working just fine for them, it must be working just fine for everyone else — and if it isn’t working for someone, it must be due to their own personal shortcomings. It can’t possibly be due to the shortcomings of a nation and society built on the enslavement of Black people, the exploitation of laborers, and the violent silencing of people who deviate from its norms. This attitude is not in the service of humanity and it was disappointing to see it still has a home at Princeton.

David N. Tobin *77

3 Years AgoBreathtaking Arrogance

Regarding Sev Onyshkevych ’83’s comment (in “Crashing the Conservative Party,” January 2023) that today “it is much more difficult to be an ‘out’ conservative than it was to be Jewish, Black, female, or gay in my day” — you will not find a better example of the breathtaking arrogance and blinkered entitlement that underlies such thinking. Please help me understand what makes Mr. Onyshkevych a reliable source to help understand and appreciate the difficulties faced by Jewish, or Black, or female, or gay students in the Princeton of the early 1980s.

Tina Madison White ’82

3 Years AgoLike Water, Willy Nilly Flowing

I confess to finding this article a disappointment. It isn’t that I disliked the political views presented or the people featured. It is that I learned little of value.

The article is structured around three tensions: 1. Has conservatism been wildly successful or is it dying? 2. The unity, then disunity between four conservatisms (political, aesthetic, academic, and elitist). 3. Brief profiles of seven archetypal conservative leaders at Princeton.

None of these devices helped me to understand conservativism, its prospects, or the people profiled. I would like to think that their thoughts and convictions run deeper than the tweet-like quotes and sartorial asides shared in this article. The four conservatisms did nothing to help me to understand the rifts within the most consequential today: political conservatism.

To my eye, the author cheapened the conservative movement. He also missed some important points:

First, conservative activists are not alone in feeling maligned, labeled, and attacked. I attended Princeton with Sally Frank ’80. I can think of few people who were treated more maliciously and who were more alone in the world. We might learn more from an article that considers the plight of any person or group that chooses to tilt at windmills.

Second, the author seemed unaware of a fundamental irony captured in this article: In one breath, many of those featured rail against indoctrination of students by those with other perspectives. A sentence later, they lay out their own agenda for indoctrination, thinly disguised by terms like “shared values” and appeals to founding fathers.

For example, Yoram Hazony is quoted, “Enlightenment rationalism was the construction of men who had no real experience of family life.” Wow. Was the Catholic Church any more experienced in family life? Were the founding fathers experienced in womanhood, servitude, or poverty?

The author, too, shares quotes that are dismissive of pronouns and the experiences of women and racial minorities. He does nothing to critically examine these. I (a trans woman) have sympathy with people who are bewildered by the recent explosion in pronouns. But we are a long way from the 51,000 varieties of Christian denominations in the world. I find those confusing. Maybe the younger generation’s emphasis on pronouns is a sign of their rejection of all the traditional institutions (religious, economic, and political) that have vied to colonize our minds. That would be an interesting article.

I don’t mind that these people have different perspectives from my own. I simply feel that the author did little to help me to understand their convictions. Nor does he help me to understand where their movements are heading.

After reading this article three times, I finally put it down. I wandered to my bookshelf and pulled out my dog-eared copy of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. I thumbed my way to a favorite quatrain: “Myself when young did eagerly frequent Doctor and Saint, and heard great Argument about it and about: but evermore came out by the same Door as in I went.”

Indeed.

Liz Hallock ’02

3 Years AgoLiberal Praise for ‘Crashing the Conservative Party’

Thank you, David Walter ’11, for the in-depth analysis of conservative trends at Princeton. The most astute observation was from Tory founder Yoram Hazony ’86:

Princeton scoops ambitious young people up, “it cuts them off from their local roots, and then they don’t go back.”

Whether you are connected to “conservatism of the elite,” “Big Business, Big Finance,” or not, people from the small towns from which we came have started to view us not as that overachieving kid down the block but as part of the “globalist” elite.

Stripping the most high-performing students from all over America, combined with economic trends that have moved jobs to coastal cities while leaving exurban and rural areas stripped of manufacturing jobs and plagued with high poverty and an opioid epidemic, is a huge problem. Princeton needs to refocus its energy into ensuring its sons and daughters are committed to working in the nation’s service, not just in D.C., or New York, or L.A., but in the smaller communities that need them the most.

As a liberal living in a very Trump-friendly region (central Washington state), it is not always easy. But liberals and conservatives alike need to join together in tearing down this wall of perceived (and real) “elitism” that is dividing our country and destroying our future.

John Milton Cooper Jr. ’61

3 Years AgoVotes in Elections

The recent article on conservatives at Princeton correctly noted that 1964 was the first election in which a Democrat prevailed in the Daily Princetonian polling. Four years earlier, at least some cracks emerged in the Republican hegemony. As a senior, I watched the candidates’ debates in the TV room at Quad. During the second one, Nixon went on in his sing song voice about children being held up to see the president, and I heard repeated cries of “Ugh!” and “Shut up, Nixon!” Those weren’t coming from the small Democratic minority. I was hearing votes change; one friend, a diehard suburban Chicago Republican, told me later that he couldn’t stop himself from voting for Kennedy. Straws in the wind.

Bruce Charles Johnson ’74

3 Years AgoConserving the Legacy of Princeton’s Founders

To be a credibly conservative university one has to seek to conserve something. Political ideology aside, Princeton has always stood for preserving links to the civilization we inherited from its founders. That is a proud legacy, and without demeaning other legacies, it deserves to be conserved.

Sam Fendler ’21

3 Years AgoTribalism and Intolerance on Campus

This article offered an interesting high-level view of conservatism at Princeton. Its finest feature is its presentation of Professor Robby George as Princeton’s last great hope for conservative students. Beyond his tremendous instruction, Professor George was a source of sanity for me during my tenure at Princeton, and I feel deeply grateful for his example.

I think the current state of affairs at Princeton should worry alumni of all political persuasions because the campus climate is producing closed-mindedness and distrust amongst students.

In my first semester, one of my teachers told me after class that my presence often made them uncomfortable because I was a white male and a representative of the U.S. military — a force this teacher considered destructive to global peace. I actually liked this teacher despite our clear differences, and I respected the opinion even while being hurt by it. But as I continued my studies, I realized this episode wasn’t what I thought it was — something of an awkward miscommunication. Instead, it was perfectly emblematic of campus ideology.

I wasn’t especially political when I came to Princeton, but I left as a principled conservative. At least some of my political evolution was due to the devout fanaticism of my progressive classmates. These classmates of mine didn’t challenge my deeply held beliefs with well-reasoned arguments and win me to their way of thinking. They simply attempted to bully me in one way or another, something I always found incredibly fascinating considering I’m a combat veteran and was, on average, about six years older than the members of my graduating class.

The author notes that the ideological battlefield at Princeton might be an effective breeding ground for future leaders of the political right. Perhaps that’s correct. I certainly believe that Princeton sharpened my conservative beliefs and forced me to defend them more strongly than I ever thought I’d have to. However, I also think the political philosophies of a substantial number of Princeton graduates — those who just want to be left alone — will be the result of fear and coercion if the current social order doesn’t change. Princeton alumni should be aware that the tribalism and intolerance we all lament as disastrous to our country’s social fabric are alive and well on our own campus.

James Allen Lane ’92

3 Years AgoThank You for Speaking Up

I’m happy that recent grads are speaking up. I am generally uncomfortable visiting the campus these days given the multiple similar stories I hear and read about.

Mark Flaherty ’90

3 Years AgoAshamed of this Age of Illiberalism

I second these sentiments. I am ashamed of this age of illiberalism that has taken hold.

Glen Lockwood ’91

3 Years AgoConservatives Have No Monopoly on Support for Freedom of Speech