This Is How Princeton’s Endowment Works

Endowments are back in the news, and PAW is here with a Q&A to clear up any confusion

Princeton’s endowment has long been a popular topic of conversation, especially since 2021, when the University reported a 46.9% return on its investments. Since then, changes to the endowment’s value have been modest, with negative returns in 2021-22 and 2022-23 and a 3.9% uptick last year. As of July 2024, the fund was at $34.1 billion.

There are many misconceptions about how endowments function and PAW is here to help.

Let us know in the comments what questions you have, and we will update this article.

How did Princeton’s endowment get to be so big?

The first endowment at Princeton was established in the 18th century to provide student scholarships. Alumni have donated to the University ever since. But it wasn’t until the presidency of Bill Bowen *58 (1972-88), when the endowment more than tripled, that it loomed so large. Bowen’s term coincided with a revolution in University investing as schools across the country tried to diversify their portfolios. During this period the trustees also established Princo in 1988 to manage the endowment.

Although Princeton is also known for its high donor participation rate — with 45% of undergraduate alumni donating to Annual Giving in 2024 — this isn’t necessarily a metric that measures endowment growth. Gifts to the endowment — also known as capital gifts — are separate from the smaller donations that many alumni give.

Over the past decade, Princeton’s endowment has had an average return of 9.2% per year, reaching $34.1 billion last July. Harvard has the biggest endowment at $51.9 billion, but Princeton ranks first in dollars per student at about $4 million per undergrad.

How is the endowment used?

According to the University, about two-thirds of the University’s $2.9 billion dollar operating budget is covered by endowment funds. Within that budget are costs related to faculty, staff, construction, and facilities maintenance. The endowment also pays for 70% of financial aid costs for undergraduate students.

Why doesn’t Princeton withdraw more from the endowment?

More than half of the endowment is restricted, meaning gifts can’t be spent but can be invested, and those returns are what the University taps. In addition, 70% is set aside to be used strictly for the donor’s purpose, such as scholarships or a faculty chair.

In general, the endowment continues to grow because the University spends about the same percentage each year. According to the 2023-24 Report of the Treasurer, that amount equaled about 5% that year. If Princeton were to spend substantially more than that percentage over an extended period, the endowment would likely shrink. As the report notes, the trustees decide each year how much to spend — usually between 4% and 6.25%.

OK, but in times of need or extraordinary circumstances, can’t Princeton take more money out of the endowment and use it to fill a shortfall?

The trustees can and have spent a greater percentage in a given year. For example, when the pandemic disrupted University operations in 2020-21, President Christopher Eisgruber ’83 announced that the spending rate was likely to be more than 6% but that such spending over a longer period would not be sustainable. The University made similar spending adjustments in 2008-09 and 2009-10, during a period of global recession, while also enacting significant budget cuts.

The University could use endowment funds to pay for research impacted by the federal funding pauses. Northwestern University announced in April that it would do just that. However, as Phillip Levine *90, an economics professor at Wellesley, points out, the endowment isn’t a “piggy bank,” and you can’t simply take money out. A large part of the endowment isn’t liquid.

The endowment is structured to be able to sustain large one-time losses, such as in 2008. As Eisgruber explained to The New York Times in April:

“What we are looking at is how best we can use resources to preserve the core mission of the University … . We said we’re going to protect three things that are critical to what it is we do. That’s our teaching, our research, and our affordability, and access to the University. And we’re going to find ways to change other parts of our operation, to draw upon other resources, to allow for temporary increases to our endowment spend rate in order to get us through this period … . We can do that kind of thing, again, with ‘temporary’ being an important word in there.”

What would happen if Congress passes an increase on the endowment tax?

In PAW’s March issue, Christopher Connell ’71 explored this question. The current endowment tax is 1.4% on endowment returns for colleges with more than 500 students and at least $500,000 in endowment funds per student. Conservative politicians have proposed taxes ranging from 10% to 35%.

When PAW revisited the issue with Levine, he explained the possible consequences of such a measure. A University — even one like Princeton — doesn’t have an infinite budget. So when push comes to shove, in a situation with less financial certainty, the University will need to make decisions about the best choices to make with its money.

“If you think about the things that the college spends its money on, you’ve got lots of faculty and staff, right? You can lay off some of them, but a lot of them have contracts … but you have to spend that money [on employees]. It’s a fixed expense. You have ongoing research labs that need to be funded. It’s very difficult to just cut those off cold turkey. They’re sort of fixed. Your facilities are your facilities. You have to maintain them, right?” The real tuition cost to students — often called access — is among the only “flexible” expenses.

Some universities have more to lose than others with a tax on endowments because of how much federal research funding they receive, as well as how much money they spend per student. Princeton makes the top five, according to a ranking by Levine in The Chronicle of Higher Education.

How could access to Princeton change if the endowment shrinks?

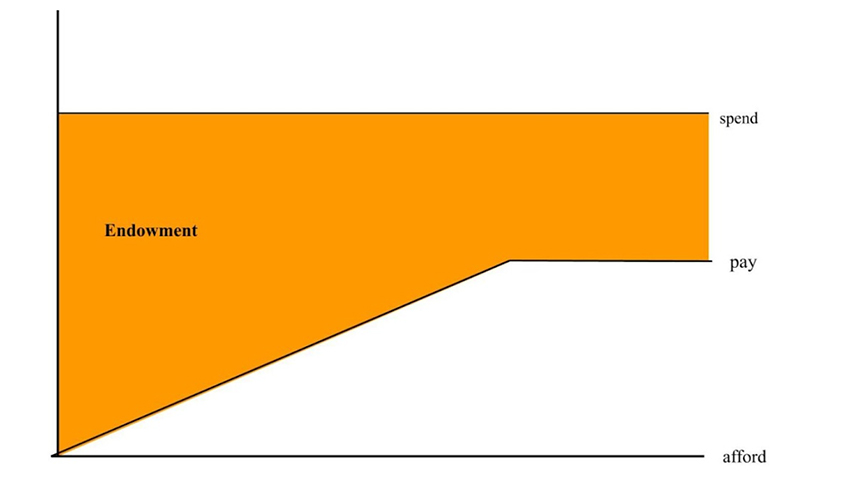

Levine showed PAW a graph (see replica below), and explained the function of the endowment in allowing students access to the University.

“You have, like, a pretty high sticker price … . But not everyone pays that. If you’re low income, you don’t pay anything,” he explained, indicating the point on the graph where the x and y axes meet.

“So if you can’t afford anything at Princeton, you pay almost nothing. Right as your financial resources increase, you pay more and more and more until eventually you get to full pay,” he said. It’s the endowment that fills in this gap and creates access for students from lower incomes.

In talking with The Times, Eisgruber suggested tough choices could have to be made, for example, between funding research and giving financial aid. “At some point, you get to really tough choices about, how good does your financial aid program have to be in order to be able to sustain the research that you do?”

In early April, Princeton’s trustees approved “preliminary budget parameters” for 2025-26, according to a news release, projecting increases in undergraduate financial aid (up 8% to $306 million) and graduate stipends (up 7% to $365 million).

2 Responses

Grady C. Grissom ’84

7 Months AgoRising Tuition Costs

Can someone explain why tuition has greatly outpaced inflation in the last 25 years? Second, is the gap between tuition and inflation associated with access to federal funding?

William H. Earle ’69

7 Months AgoConfusing Graph on Access

The graph accompanying this article is very poorly done. It clarifies almost nothing. Why are there no labels on the x and y axes?