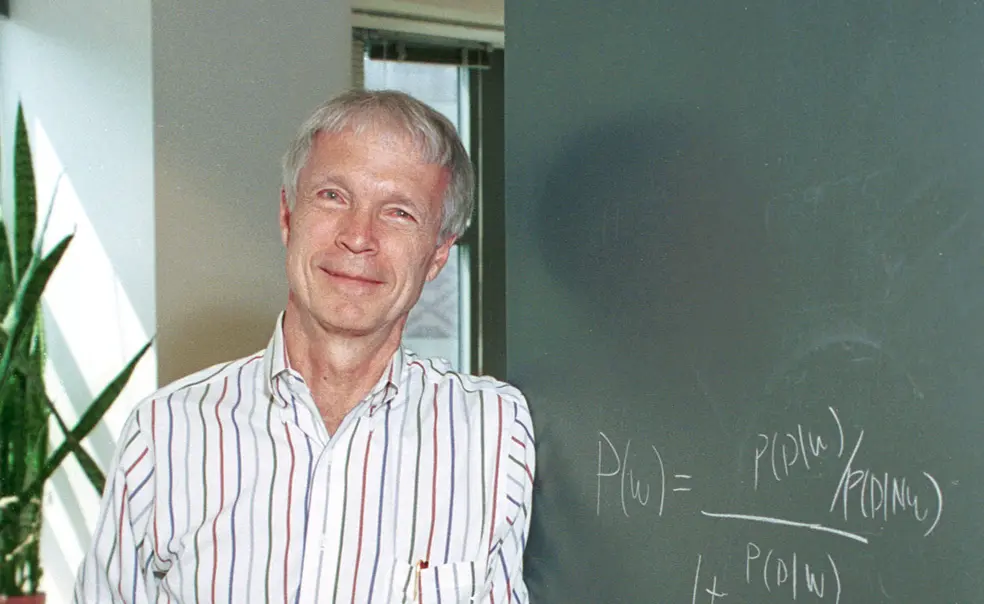

John Hopfield Wins Nobel in Physics for Work on Artificial Neural Networks

The emeritus professor at Princeton share the prize with Geoffrey Hinton, a professor at the University of Toronto

John Hopfield, an emeritus professor at Princeton whose work has spanned physics, biology, neuroscience, and chemistry, was awarded the 2024 Nobel Prize in physics for his research on artificial neural networks that helped pave the way for machine learning applications. He will share the prize with Geoffrey Hinton, a professor at the University of Toronto.

The award, announced Oct. 8 by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, recognizes Hopfield and Hinton “for foundational discoveries and inventions that enable machine learning with artificial neural networks,” according to a press release.

Hopfield “created an associative memory that can store and reconstruct images and other types of patterns in data,” the release said. Now known as the “Hopfield network,” the groundbreaking research was first published in 1982.

Princeton celebrated the award with a news conference that drew about 350 people to Frick Laboratory’s Taylor Auditorium — students, administrators, media, staff, and faculty, including Nobel laureate James Peebles *62, who sat in the front row. Unfortunately absent was Hopfield, who happened to be visiting England and joined the event by Zoom.

“I would have planned my life a little differently had I known that I should be in Princeton tomorrow,” Hopfield quipped as the staff was setting up his video connection. “But one can work with what one has.”

The crowd gave Hopfield a roaring round of applause as he cracked a gentle smile on two large projection screens at the front of the auditorium.

President Christopher Eisgruber ’83, in his introduction, quoted Hopfield’s remarks about “science that gets done for curiosity’s sake” and the breakthroughs this often yields. “John, I very much hope that Congress is listening as you speak,” said Eisgruber, who advocated for “generous funding” for the National Science Foundation and other agencies.

Professor Mala Murthy, director of the Princeton Neuroscience Institute, said that the Hopfield network “revolutionized our understanding of neural processing and laid the foundation for modern computational neuroscience and artificial intelligence.” Hopfield also had a foundational role in Princeton’s neuroscience community, Murthy said, recruiting faculty in the early 2000s to help build what later became the Princeton Neuroscience Institute. And when he visits his emeritus faculty office, she added, “there’s often a long line to visit with him.”

Hopfield, 91, joined the Princeton faculty in 1964 and served as a professor of physics until 1980, when he departed for Caltech. He returned to Princeton in 1997 with an appointment in molecular biology but also holds associated faculty status in physics and neuroscience. He transferred to emeritus status as the Howard A. Prior Professor of the Life Sciences in 2008.

Responding to a handful of questions submitted by reporters, Hopfield spoke about his path in the sciences, straying to the fringes of his initial discipline, physics, and intersecting with other fields, most notably biology. He described interdisciplinary work as “the kind of science which has such extensive possibilities, as well as being the possibility that you just don’t find anything at all — a risk you have to take.”

One question invited Hopfield to discuss the use and spread of artificial intelligence, noting that his co-winner, Hinton, has been outspoken about the dangers of unregulated A.I. In a long response, Hopfield said he’s “worried about a world of control” and referenced unforeseen consequences of technology as presented in fiction, including George Orwell’s 1984 and Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle.

“I’m worried about anything that says … ‘I’m faster than you are, I’m bigger than you are, and I can also run you; now can you peacefully inhabit with me?’” he said. “I don’t know. I worry.”

Hopfield and Hinton will share the prize of 11 million Swedish kroner, about $1 million.

Hopfield is the 23rd Princetonian to win the Nobel Prize in physics, and his award is the 24th with ties to the University (alumnus John Bardeen *36 won twice). Syukuro “Suki” Manabe, a senior meteorologist in the Program in Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, shared the prize in 2021 for devising new methods to describe Earth’s climate and predict its long-term behavior.

In addition to Manabe and Hopfield, four other Princetonians have won the physics award in the last decade: Peebles (2019); alumnus Kip Thorne *65 (2017), Professor F. Duncan Haldane (2016); and former professor Arthur McDonald (2015).

More than 50 Nobel Prizes have been awarded to Princeton faculty, research staff, and alumni, beginning in 1919, when Woodrow Wilson 1879 received the Nobel Peace Prize. In 2021, a record five Princetonians were honored with Nobels for economics, chemistry, physics, and peace.

No responses yet