“A place for everything, everything in its place.”

— Benjamin Franklin

Let me tell you about the old advance-ticket office at Dillon Gym. Stand before the grand Gothic arches and gargoyles of the Dillon entrance, then go around the east end of the façade toward Elm Drive, curl around the outcropping below the interior balcony, go down a few steps a full level below the main entrance, and there it was: behind a windowless medieval 80-pound wooden door, Princeton’s tribute to the Black Hole of Calcutta.

If you wanted to see Bill Bradley ’65 play basketball, you recall this. A date and time possibly dictated by the I Ching — no one seemed to know how — would be posted in the Prince for the student allotment to be released for some number of games, everyone with a class or rehearsal that conflicted would scramble to find somebody to cover for him (sorry, ladies, only hims at this point), and hours beforehand an avalanche of students with coupon books would descend on the foreboding door. I would say it resembled Spamalot without the orchestra, except at least once, for no apparent reason, Tiger Band showed up to serenade those in line.

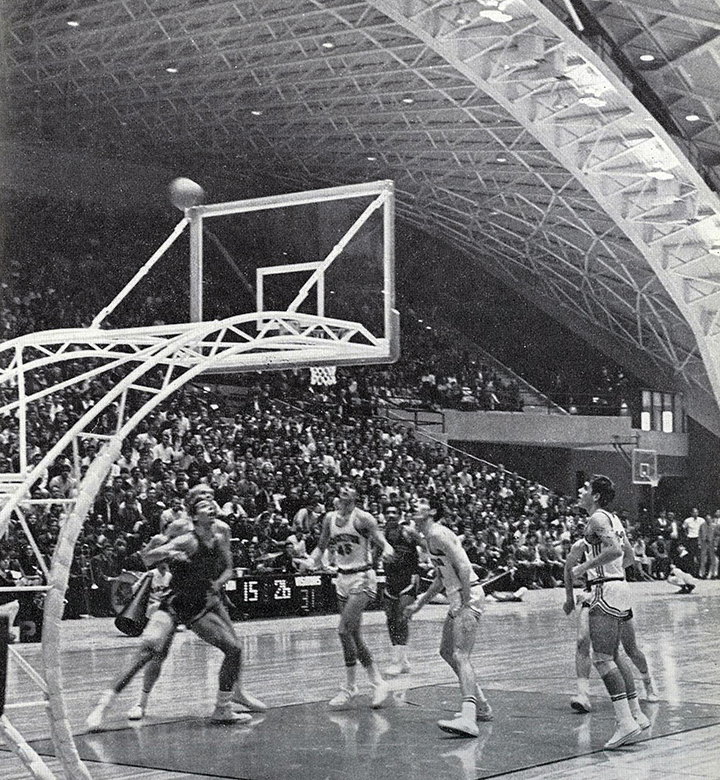

There were 3,000 or so seats in Dillon. A few were reserved for the opposition Bradley was about to mortify; some for President Bob Goheen ’40 *48 and the administration and faculty; some for trustees and alumni who were kind enough to pay the electric bill for the huge barn; some for the colorful friends of coach Butch van Breda Kolff ’45; and some for the fawning local press, who got to see something like Bradley maybe every three or four decades. All of them besieged Ken Fairman ’34, the athletic director and ringmaster by default. Meanwhile, there were 3,200 students, of whom 3,172 were basketball fanatics. Hence the popularity of the besieged little airless bunker below, the only gate to the Nirvana of the insufficient number of lucky tickets (which also seemed randomly determined somehow) possibly to be obtained with your precious coupon book. Along with the stereotypical taking-an-exam-for-which-I’ve-never-studied nightmare, the Dillon ticket office may be my most recalcitrant subconscious Princeton memory.

So it will not surprise you to find that L. Stockwell Jadwin ’28 and his mom Ethel are two of my great heroes. Stockwell, a star hurdler who died eight months after his graduation in one of those awful auto accidents that beset Princeton in the 1920s and ’30s, had tied an indoor world record while running for Princeton, and the irony that we still had no indoor track, even in 1964, was not lost when his mother died and unexpectedly left $27 million to the University. Goheen, who had a list of capital priorities left over following the $53 million campaign just completed, got together with our old friend Cupe Love ’22, who chaired the trustees’ capital committee, and they started allocating funds from the Jadwin bequest, then the largest unrestricted gift in Princeton’s history. The new math building, physics building, and their joint library, already in the design-discussion stage, were greenlighted almost immediately. They became (new) Fine Hall and Jadwin Hall.

One other person who was prepared for such a windfall was Ken Fairman, he of the subterranean, subhuman advance-ticket booths. The athletic director had tried to get a new intercollegiate gym into the $53 million campaign, but the E-Quad and other dire necessities had intervened, so he settled for the highly efficient and flexible Caldwell Fieldhouse, a great locker facility for the football, baseball, lacrosse, and track teams. But he continued to work on his plans and had, with remarkably little assistance, come up with what amounted to an astonishing vision. In an era of boxy indoor athletic barns giving way to kitschy round arenas that provided mediocre sightlines, he put together idealized plans for five different indoor sports, fitted them together like a jigsaw, and then sketched an enclosure around them. The result, referred to as a “cage” at the time given the multisport nature of the building, all ready for display at Alumni Day 1965 when the Jadwin bequest was announced, was essentially identical to the current Jadwin Gym, with its three overlapping shells.

When I got to campus in September 1966, construction had begun, and in short order I started haunting the job site, in part because the project was unique, and in part because I had personal interest in being delivered from the peculiar shortcomings of Dillon Gym. Like the rest of the student body, that included the ticket-distribution purgatory, but had quickly expanded beyond, as I joined WPRB and went into training as a sports announcer. Which brings us to the bathtub.

Built into Dillon Tower is a glassed-in observation facility then used by the commercial radio station in town that paid to broadcast the games, Herb Hobler ’44’s WHWH. WPRB, the student station, which didn’t pay a thing, was placed accordingly. Above the two big southern doorways to the basement locker rooms beyond the baseline are, for no good reason, cinderblock enclosures the size and shape of a generous bathtub, accessible from the adjacent bleachers when they’re pulled out. Three people and a tiny portable audio board can fit into one, sort of, and peek around the adjacent stands to see perhaps 96 percent of the basketball action on the main court. I was training with other freshmen in one, and the on-air broadcast team used the other.

So Jadwin Cage offered salvation not only to the 49.6 percent of the student body who got shut out of Dillon for any given game — the projected capacity for basketball was 7,000 or so, and expandable beyond that — but also for the broadcasters, for whom the prospect of not calling the game sidesaddle was alluring beyond hope.

Thus I slunk, hardhat-less, through the Jadwin construction site any chance I could get, which was weekly, sometimes more. I honestly have no idea why security was so lax. I was always alone, and it was sort of intoxicating to try figuring out how the various huge rooms for fencing and wrestling fit into the balconies, squash courts and galleries, the huge dirt surface in the basement, and the interconnect to adjacent Caldwell, which cleverly negated the need for further expenditures on locker facilities. The use of concrete and steel was far beyond anything I had ever imagined (keep in mind, Wright’s Guggenheim building in New York had been open for only seven years), and the effect of frequent visits was that of watching a mystery novel unfold in 3-D. I must have spent hours simply staring at the gargantuan pyramidal steel post in the cellar that holds up the main floor, still unique in my experience.

Which relates directly to the excruciating progression of delays that clung to the Jadwin Cage construction, seemingly beginning as Fairman first handed out pictures of his model. Design specs took extra time, steel fabrication took extra time, rework on the almost-experimental neoprene roof with impervious liquid coating that was light enough to allow the vast open space of the gym floor took extra time, concrete finishes took extra time. Originally scheduled for fall 1967, the opening rapidly moved back to mid-1968, then on to October. The Prince joke issue of January 1968 breathlessly documented the collapse of the construction into a pile of rubble, blaming it on a Yale engineer.

The 1968-69 basketball season opened in Dillon on Dec. 14, then the Dartmouth/Harvard home weekend in January was kept there as well. Ticketing was a shambles. The Jadwin opening was yet again promised, for Jan. 25 against Penn on national TV (50 years ago this month), but I’m not sure anyone believed it. When it actually happened, those of us who showed up early — in our case to find out where our broadcast position was, and whether our communications lines really had been run — didn’t really believe it was happening until the teams appeared on the court. Captain Chris Thomforde ’69’s team was stoked; he dominated Penn with 20 points, Geoff Petrie ’70 had 19, John Hummer ’70 16, and the Tigers beat Penn for the second time that season, 74-62. They won 11 straight from there out and became the first 14-0 team in Ivy history. And on 103.3 FM, John Barnard ’69, Ed Labowitz ’70, and I called the game for the WPRB audience from about two-thirds of the way up the south bleachers, perhaps 50 feet from center court instead of 150 feet away in a bathtub around the corner. I breathed a little prayer the huge steel pyramid we were sitting on would perform to spec.

That season’s basketball championship has been followed by 18 others, plus 14 in men’s fencing, 17 in squash, 10 in wrestling, and 20 in indoor track. And intriguingly, Jadwin Gym, not conceived or built with women at all in mind, opened only three months before coeducation was approved. The women, given full opportunity of such a standout facility, have used it to build the best programs in the league, with 13 basketball, 10 fencing, six squash, and nine indoor track championships. Princeton’s success in athletics since the day Jadwin opened, beyond the 118 Ivy titles, is a tribute to a huge group of Princetonians, but no one more than Ethel Jadwin, her beloved son Stockwell, and Ken Fairman.

Very cagey.

3 Responses

Clay McEldowney ’69

7 Years AgoMissing Highlight

Gregg:

You omitted one important highlightt from your otherwise excellent article: the first varsity event to take place in Jadwin's center court, and when.

M. Wells Huff ’52

7 Years AgoKudos for PAW Online

For me, PAW Online is a great breakthrough, coming at a time when it is far easier to look at electronic over printed pages. Well organized and easy to access. Bravo.

John Turitzen *81

7 Years AgoA Great Playground

For a kid growing up in Princeton, Jadwin Gym under construction was a great playground to explore, with its unlit underground levels and mysterious rooms. Three of us discovered the squash courts when we felt our way down the pitch-black spectator steps and almost fell over the back wall into the void of the court. Those were great days to have childhood adventures, before the era of liability concerns, safety regulations, and security worries.