Alums Researching Liquid Biopsy for Cancer Diagnosis Face Funding Cuts

The people who cut Graham Read ’15’s program likely didn’t know they cut prostate cancer research

In late February, Graham Read ’15 was looking forward to an article featuring his work on early prostate cancer detection coming out in the next Princeton Alumni Weekly. He did not expect that around the same time, the website for his post-doctoral program would disappear, and ultimately the program, funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences — one of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) — would be cut.

What is happening to Read is happening to scientists all over the country, as more research grants are cut, funding renewals go unprocessed, and academic institutions embark on hiring freezes to cope with uncertainty. “What we can say today and has been true since [the Trump] administration started — the theme is uncertainty,” says Monica Bertagnolli ’81, who resigned in January from her post as director of the NIH.

PAW spoke again with two of the scientists — Read and Chloe Atreya ’98 — whose work was highlighted in the March feature story about early cancer detection to find out how the new research funding landscape is affecting them. Both Read and Atreya work on liquid biopsy, a blood test that detects cancer-specific DNA and RNA.

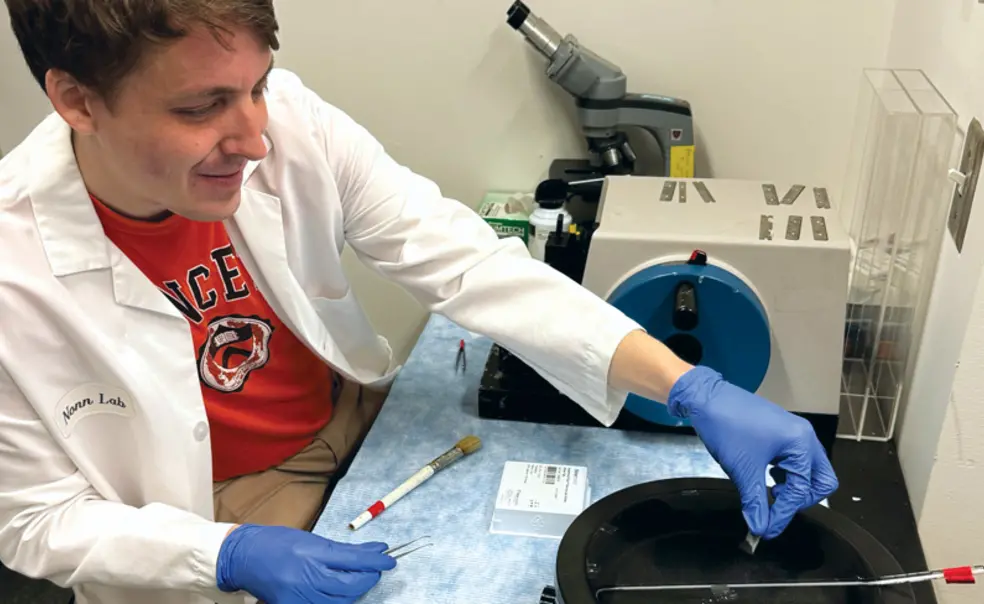

After receiving his Ph.D. in 2023 in molecular biology at UCLA, Read took a position as postdoctoral fellow at the University of Illinois Cancer Center, sponsored by an Institutional Research and Academic Career Development Award (IRACDA). The IRACDA program specifically supports scientists who also strive to be outstanding teachers; Read’s program was set up as a 75/25 research-to-teaching split. Until recently, the IRACDA program supported approximately 200 scientists at U.S. academic institutions. “We weren’t given any reason behind the program cut beyond ‘shifting institutional priorities,’” says Read, “though the program itself contained language about a diverse workforce.” Since the academic institution applies for an IRACDA award independent of what research the fellows work on, the people who cut Read’s program likely didn’t know they cut prostate cancer research.

Read happened to be near the end of two years as a postdoc, so he decided to job hunt. While he loves doing research and teaching, he focused his search on positions that prioritize teaching because, he says, “I don’t feel like there’s much research infrastructure left right now.” He is disappointed to have to move away from biology research. “You get to be the first person who sees something, and that is so exciting,” he says. But he says he hopes that in his new teaching-focused position, as a visiting assistant professor in the biology department at Macalester College, he can help his students learn as much as possible.

Will someone else continue with his prostate cancer early detection research? Read says he hopes so, but that this is not the only funding difficulty the lab faces. “When you have people who have built specialist expertise, you need them to keep moving things forward.” Beyond the lab, Read worries about the effects of the IRACDA cuts on teaching in the wider academic community. “Many of us fellows taught at community colleges or minority-serving institutions,” he says. His own teaching was at Governors State University, a nearby community college. “They ran courses that they wouldn’t have been able to otherwise because IRACDA fellows came to teach one class per semester each for them.”

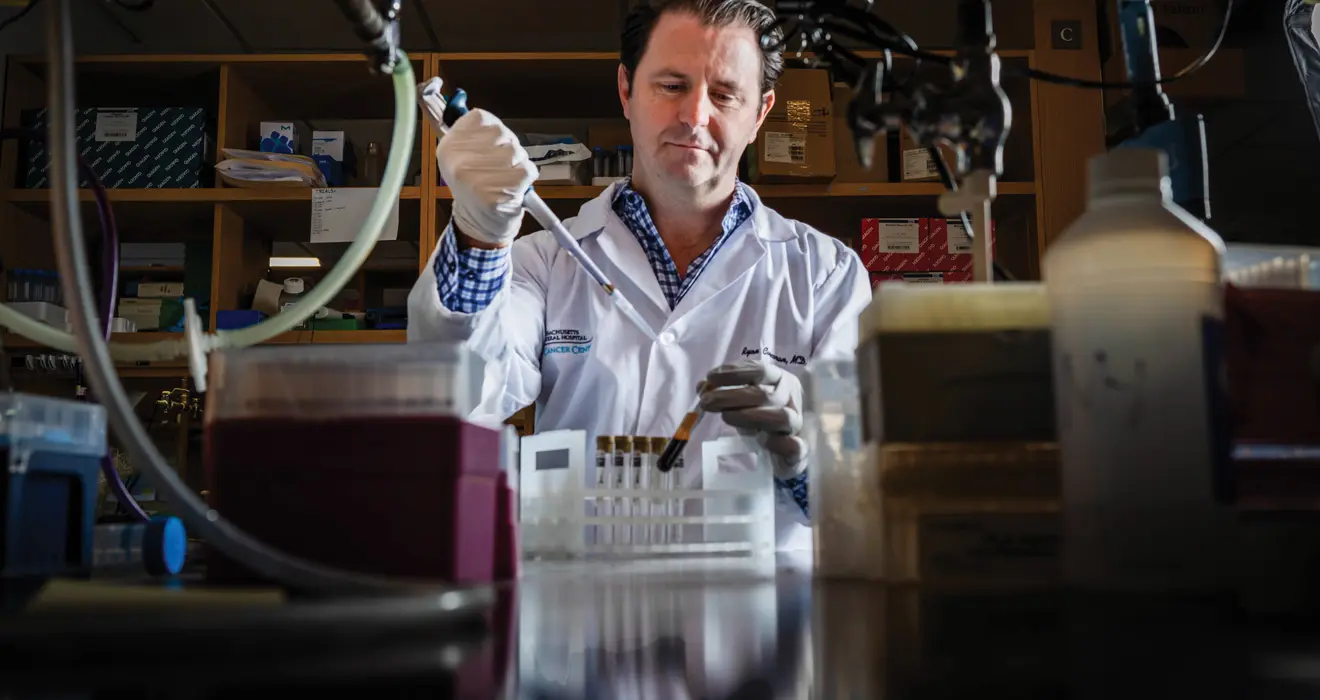

Atreya is a gastrointestinal oncologist at the UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center and also the director of mentoring and faculty development for the Division of Hematology and Oncology. She says that while federal funding cuts impact research, the impacts are most felt by trainees and junior faculty. Grants have been terminated because someone is in an underrepresented group or because the project involves an international collaboration. “It would be one thing to change the priority of prospective grants, but the fact that they are terminating existing grants that are actively supporting people is pretty devastating,” she says.

Atreya worries most about the people who are at the end of years of training and are pivoting to industry or becoming clinicians without a research component. “I mentored a superstar whose dream job was to be a statistician at the FDA — she ended up getting that job but decided to move to Europe. Our graduating fellows are on the cusp of launching their careers, and we may lose excellent researchers.”

UCSF has responded to the uncertainty with a hiring freeze, which, among other things, affects clinical trial recruitment, including liquid biopsy trials. “We were in ‘growth mode,’” Atreya says, “and now we are in ‘we’re not sure’ mode.” In terms of her own group, she says it recently submitted a grant proposal to the American Cancer Society, rather than to the NIH. “We are also establishing new collaborations for liquid biopsy work with nongovernmental entities and joining international consortiums.”

“We have never before seen this kind of withdrawal from research funding,” says Bertagnolli. Most of the money goes to continuing grants that support five- or seven-year research programs, she says, and now researchers are seeing grants cut in the second, third, or fourth year. “When those cuts happen, you often lose everything you have invested,” she says.

Long-term investment has resulted in the ability to use cell-free DNA to detect and guide the treatment of cancer. “Like so much that NIH funds, this kind of work [on liquid biopsy] is fundamental,” says Bertagnolli. “It’s been under development for a long time and is now really starting to show benefits that matter to patients.”

Atreya says she thinks about what is happening in the way she thinks about cancer itself. “We are losing the tumor suppressor genes safeguarding research funding,” she says. “It will take a long time to rebuild after this leveling.”

Bertagnolli adds, “I do have optimism. There are still people in this country who care and cherish the NIH. I hope that we go through this recalibration period quickly, and then we can move forward.”

1 Response

Lisa Feinstein ’95, D.V.M., M.P.H.

7 Months AgoFunding Liquid Biopsy Research

My 19-year-old daughter Kate died of a rare ovarian cancer called primary ovarian mucinous adenocarcinoma on May 23, 2024. There are no definite screening tests for her cancer since cancer antigens like CA125 are often normal, and ultrasound imaging can fail to distinguish malignant cysts from the more common, benign mucinous adenoma. Assuming her large cyst was benign, her gynecologist performed a laparoscopic cystectomy which spread cells inside her abdomen and upstaged her cancer to stage 3 at the staging surgery. Gynecologists aim to preserve the ovary of young women, yet mucinous ovarian cancer affects younger women compared to the other ovarian cancers. It is terrible that there is no way to fully know that an ovarian cyst may be cancerous until the pathology results. Liquid biopsy is the future and needs more funding to continue its research goals.