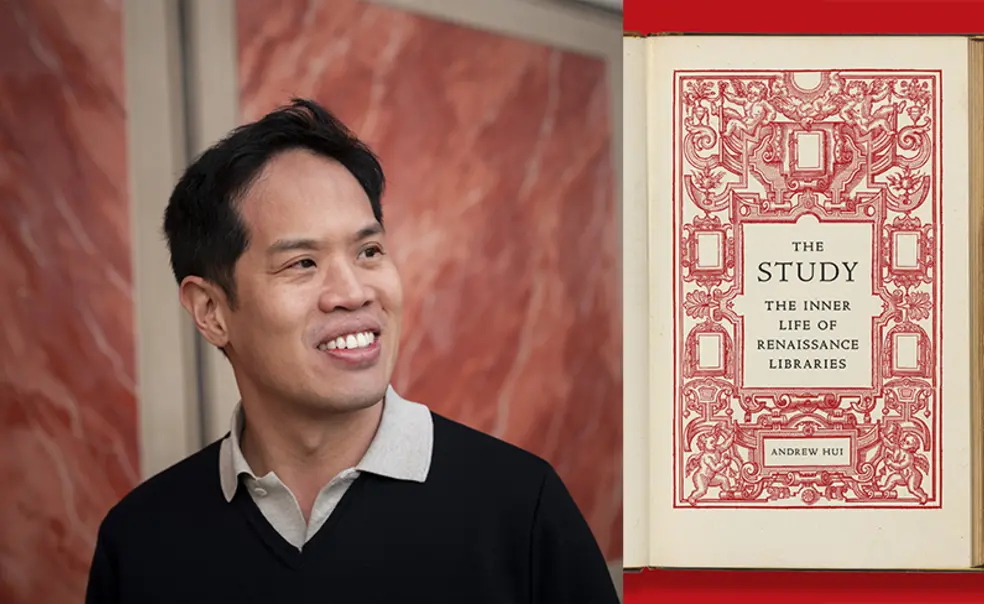

In Book on Renaissance Libraries, Andrew Hui *09 Studies the Study

In The Study: The Inner Life of Renaissance Libraries, Hui examines the origins and the ambivalent nature of personal spaces devoted to books

At the beginning of the COVID pandemic, Andrew Hui *09 was searching for his next book topic. He wanted a subject, he says, “that required no traveling and emerged from deep within my core memories, my memory palace.” One sleepless morning in his apartment in Singapore, he decided to focus on libraries.

The product, almost five years later, is The Study: The Inner Life of Renaissance Libraries, which has received admiring reviews in The Wall Street Journal and London Review of Books. “This study studies the study,” Hui writes at the start of his book. “It investigates how Renaissance humanists created an intimate healing place of the soul — the studiolo — as a personal library of self-cultivation and self-fashioning.” He also describes how a love of books leads to madness in fictional characters such as Don Quixote and Dr. Faustus.

Hui grew up in a Dallas suburb. “As an immigrant to the U.S. whose first language was not English, going to the public library and spending a lot of time in used bookstores was both an engagement with and an escape from contemporary American culture,” he says. “I wasn’t a computer nerd, I wasn’t an athlete. My niche was the bookworm, the intellectual.”

He graduated from St. John’s College in Annapolis in 2002 and then studied comparative literature at Princeton, where, he writes in his 2019 book A Theory of the Aphorism: From Confucius to Twitter, “I read Erasmus, Bacon and other humanists with Leonard Barkan, Anthony Grafton and Jeff Dolven; Nietzsche with Alexander Nehemas; and early Chinese thought with Martin Kern and Willard Peterson.”

Grafton made a cameo appearance in a “Renaissance boot camp” that Hui taught in the summer of 2020 for Yale-NUS College, an online course that helped him shape his book on Renaissance libraries. “I had a handful of students whose summer internships and travel abroad had been canceled, and I wanted to give them some intellectual sustenance and introduce to them the Renaissance masterpiece. The parts of the course fell into place easily, and that became the spine of book,” says Hui, who moved to National University of Singapore after Yale-NUS College closed earlier this year.

In the first half of the book, Hui describes how the personal library emerged as a place of study, reflection, and solace in the Renaissance, a process that began with the 14th century Italian poet Petrarch and culminated with Michel de Montaigne, the 16th century French essayist who, Hui says, “embodies both the active and contemplative life. He’s holed up in his private tower, but he’s also managing his estate.”

Figures such as Montaigne were able to amass personal libraries in large part because the emergence of printing made books far cheaper and more accessible, which came with risk, Hui says. “In the early age of print, you have complete information overload; people get unhinged.”

That phenomenon was manifested in fictional characters “who have a tendency [toward] paranoid delusion,” Hui says. He considers several such figures in the second half of the book, including Don Quixote, who confuses the romances he reads with reality, and Doctor Faustus, a scholar who sells his soul to the devil for 24 years of magical power, as depicted in the early 17th century play by Christopher Marlowe.

“Those two types — Montaigne and Faustus — are always in tension,” Hui says. “Montaigne himself talks about his melancholia. There’s a constant undertone of sadness and mourning and nostalgia in his prose. For all people who spend a lot of time in books, there’s always a danger of going overboard. You need a room with a view, a room with air and light, or you live in a dungeon of solipsism and narcissism.”

No responses yet