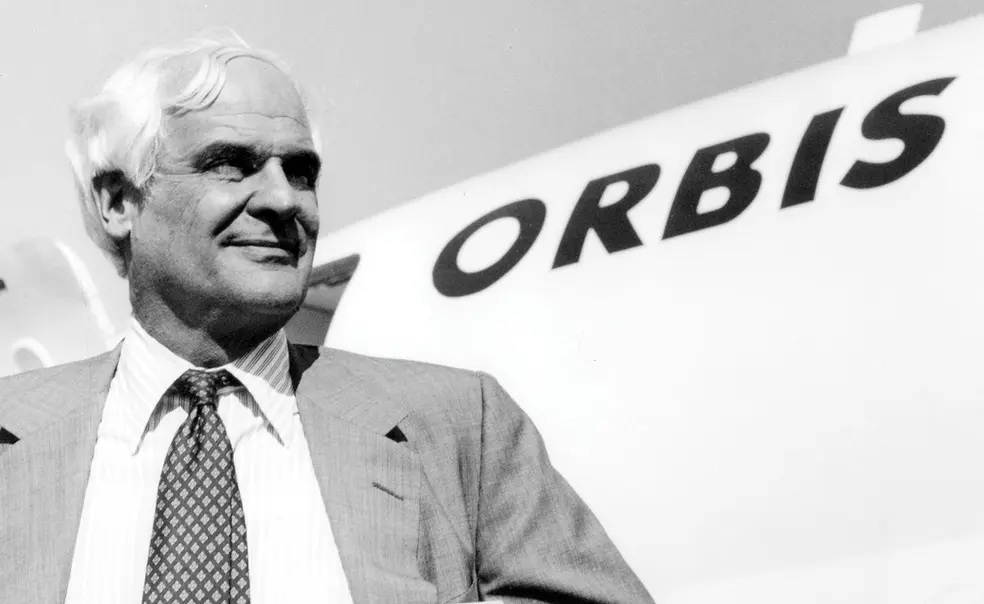

David Paton ’52 Brought Ophthalmologists to Developing Nations

Aug. 16, 1930 — April 3, 2025

In the late 1960s, ophthalmologist David Paton ’52 developed a sense of professional wanderlust. He traveled widely as an instructor in Central and South America and visited colleagues in Russia, Thailand, and South Africa to study surgical techniques, all the while thinking about ways to improve eye care in places with the greatest need.

Drawing inspiration from the SS Hope hospital ship that brought medical care to patients in developing countries, Paton envisioned a more nimble solution: a flying teaching hospital for ophthalmology. It could operate on any commercial runway, and the hands-on instruction would have a “multiplier effect” as local doctors learned the newest methods of eye surgery and passed on the knowledge, Paton explained in his 2011 memoir, Second Sight: Views from an Eye Doctor’s Odyssey.

It would take more than a dozen years for Paton’s “Project Orbis” to take flight. Facing fundraising challenges and skepticism from his peers in the medical community, he relied on a board of business leaders, lawyers, and philanthropists, including a handful of Princetonians and longtime friend Betsy Wainwright, the daughter of Pan Am CEO Juan Trippe. Their collective work produced a custom-fitted DC-8, equipped with an operating room, recovery room, and classroom with state-of-the-art audio-visual tools.

From its maiden voyage to Panama City in 1982, Project Orbis was a global sensation, attracting an enthusiastic corps of volunteer faculty who traveled to 20 countries and trained more than 1,000 doctors in its first year of operation.

“The plane is really the best example of functional diplomacy I’ve ever seen,” says Dr. Hunter Cherwek, vice president of clinical services and technologies for what is now known as Orbis International. “We have team members from over a dozen countries, all of them trained in different systems and different cultures and different languages. But when we come together, the mission is so clear, the purpose is so clear. It’s all about patient care and skills exchange.”

After more than four decades, Orbis International remains a vibrant provider of education and care, through its flying eye hospital (now in an MD-10) as well as virtual training programs. In 2024, the organization provided more than 2.2 million eye screenings and exams, 53,000 surgeries, and 38,000 trainings for eye care professionals and community health workers, according to its annual report.

Paton left Project Orbis in 1987 but eventually returned in an advisory role and was on hand to witness its expansion into telemedicine and distance learning. “I think what he was the happiest about was how far we’ve come, how much we’ve grown, but we kept that genetic code of innovation,” Cherwek says.

Paton’s philanthropic instincts and knack for bringing people together were evident during his time as an undergraduate biology major at Princeton, according to longtime friend James A. Baker III ’52.

“What struck me about David — from the first time I met him at The Hill School through our days as roommates at Princeton to the very end — was that he was a gentle human being who always wanted to do the right thing,” Baker told PAW in an email. “At Princeton, that meant being the best and most engaged student that he could be. It also meant showing interest in others rather than being solely focused on himself.”

Paton’s father, R. Townley Paton 1925, was an innovative eye surgeon who founded the first eye bank to collect donated eye tissue in the United States. David was drawn more toward teaching than private practice, serving much of his career in medical school faculty and administrator roles. Academia suited his personality, he wrote, allowing him to consider big ideas.

According to his son, D. Townley Paton, he loved to talk about the changes reshaping medicine today, such as remote surgery and the use of artificial intelligence, even as he began to deal with dementia in the final years of his life.

“He was a sweetheart until the moment he died,” Townley Paton says. “His whole passion was to change the world and help people.”

Brett Tomlinson is PAW’s managing editor.

1 Response

Rocky Semmes ’79

2 Weeks AgoInvest in Sharing and Caring

Nobody loves war but the arms-maker, which begs the question why the separate ideas of Joseph Nye Jr. ’58 and David Patton ’52 are not yet merged, mixed, and married (Lives Lived and Lost, February issue). Mr. Nye coined the term “soft power” and Mr. Paton pioneered the concept for a flying teaching hospital of ophthalmology.

Mr. Nye (“the dean of political science”), defined soft power as “the ability to achieve your goals ... because people in other countries find your ideas attractive, identify with your culture, and follow your example.” Mr. Paton’s concept became Orbis International, training over a thousand foreign doctors in its first year of service. That initial aircraft was called “the best example of functional diplomacy ... ever seen.”

Which leads one to wonder why no administration of our federal government has considered one less squadron of F35 fighter aircraft, or one less battalion of M1 Abrams battle tanks in order to support two or three hospital ships, or medical teaching airframes, to share U.S. medical expertise globally.

Continued investment in nuclear weapons for use against other nations will only lead to the eventual (and disastrous) use of one such item. Alternatively, gradual and incremental investment in sharing-and-caring for peoples of other nations may eventually end wars altogether. In the words of the old bromide, “nothing ventured, nothing gained.”