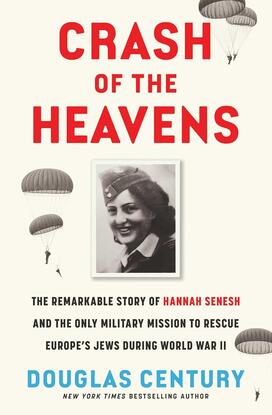

Douglas Century ’86 Profiles World War II Paratrooper Hannah Senesh

The book: This book details the untold story of Hannah Senesh, a World War II paratrooper whose bravery left a lasting impact. Senesh emigrated from Hungary to the British Mandate for Palestine in 1939 at 18. She dreamed of becoming a poet and a schoolteacher but instead became a paratrooper and was tasked with sending and deciphering British radio codes. During the war, Senesh was captured and endured months of torture, but she refused to give up any information about her mission. She ultimately died before a firing squad and is today known as the “Jewish Joan of Arc,” because of her immense bravery. Crash of the Heavens (Avid Reader Press) recounts Senesh’s life and afterlife, including some of the writings she left behind which are still read and celebrated today.

The author: Douglas Century ’86 is the author and coauthor of numerous bestselling books including Hunting El Chapo, Under and Alone, Brotherhood of Warriors, Barney Ross: The Life of a Jewish Fighter, The Last Boss of Brighton, and Takedown: The Fall of the Last Mafia Empire. His World War II nonfiction narrative, No Surrender, coauthored with Chris Edmonds, was the recipient of a 2020 Christopher Award. A veteran investigative journalist, Century has written for The New York Times, Rolling Stone, Billboard, The Globe and Mail (Toronto), and The Guardian. Century graduated cum laude from Princeton, where he studied English and wrote regularly for The Daily Princetonian and the Nassau Literary Review.

Excerpt:

Hannah lit her kerosene lamp and picked up her Biro ballpoint pen. Flipping the page in her notebook, she inked the date in the European fashion—1943.1.8—then boxed the date with a rounded rectangle. In neat, flowing Hebrew script, she began to take stock of what she had lost.

The world was entering the fourth calendar year of that cataclysmic war. She hadn’t seen her mother since September 1939 or her brother since July 1938. In fact, she had no idea if either of them was safe—or even alive. “I can think of nothing now but my mother and brother,” she wrote. “I’m sometimes overwhelmed by dreadful fears. Will we ever meet again? And one question keeps torturing and tormenting me: Was what I did intolerable? Was it unmitigated selfishness?”

She’d lost her family forever—or at least it felt that way. She’d lost her sense of joy, of purpose—she’d even lost her sense of self. A few days earlier, while she had been working at the Haifa shipyard harbor, one of the other kibbutzniks had playfully asked her whether she considered herself to be a “good” person. She later pondered the question. “Perhaps I’m not good. I’m cruel to those who are dear to me, who love me. I only appear to be good. The truth is, I’m hard-hearted with those I love, perhaps even with myself.”

She’d also lost her initial idealism about what a life of self-sacrifice and physical toil in the Land would entail. In fact, she’d go mad soon if she didn’t escape from the monotony of the kibbutz. Her high expectations had come crashing down into reality, like huge whitecaps against Caesarea’s rocks. She was isolated and lonely; the tedium of laundry duty and her latest position—kibbutz store clerk—was soul numbing.

“I hate my work. It’s a pity to waste more years of energy and strength on something I so dislike doing, and which will hinder my development in other directions,” she wrote. She then chastised herself for complaining—that was not in the socialist kibbutznik ethic of selfless sacrifice—but still couldn’t rid herself of the belief that some of the most precious years of her life were being wasted. She had so much more to contribute to the “upbuilding of Zion” than hand-washing socks and stocking shelves in the communal storeroom. “I feel like an empty vessel,” she wrote. “Or more precisely—like a vessel with holes in it, so that everything poured into it spills out.”

The robotic days of work often left her feeling so drained that she strained even to write in her diary. Writing—the one thing she felt she could not live without—escaped her. Some nights the ink in her ballpoint pen went dry; other nights her little lamp ran out of kerosene—and in the flickering darkness she found she could no longer even organize her thoughts. “I often recall Scarlett in Gone with the Wind. At difficult moments she would stall until ‘some other time.’ I’m that way: I’ll consider what life is about, the value of society, the purpose of man, the future—at some other time.”

Finally a letter arrived from her mother. Hannah recorded her thoughts in her diary on January 22, 1943:

“I’m well, only my hair has turned a bit gray,” Mother writes. It’s obvious, reading between the lines, why her hair has turned gray. How long will all this go on? The comedic mask she wears, and those dear to her so far away? Sometimes I feel a need to recite the Yom Kippur confession: I have sinned, I have robbed, I have lied, I have offended—all these sins combined, and all against one person. I’ve never longed for her the way I long for her now. I’m so overwhelmed with this need for her at times, and with the constant fear that I’ll never see her again. I wonder, can I bear it?

Her mother was safe, at least for the time being. Hungary’s Jewish community was the last haven in Central Europe and the Balkans, home to the largest Jewish community still untouched by the Nazis, having swelled to a million with the arrival of fugitives from Poland, Yugoslavia, and Slovakia. But what about the Jews who couldn’t go there, the ones trapped in those countries and possibly doomed to die there?

As if a thick gray sea mist had lifted over the ruins of Caesarea, revealing a brilliant blue sky, Hannah had an epiphany: She needed to return to Budapest. “I feel I must be there during these days in order to help organize the youth aliyah, and also to get Mother out,” she wrote. “Although I’m quite aware how absurd the idea is, it still seems both feasible and necessary to me.”

To return—yes, that was certain. But how?

Hannah found a few men on the kibbutz who’d already enlisted in the Palmach and a few others who’d served in the British infantry and fought in the Desert Campaign. They could see her passion but raised the obvious questions: Did she really think the British Army would accept a young Jewish woman with no military experience and then train her for some kind of special operations unit? Even if she did enlist—yes, it was true, many Jewish women in Palestine, if they were unmarried and childless, had volunteered for service—what British officer in his right mind would authorize sending her on a rescue mission back into the heart of occupied Europe in the middle of the chaotic world war?

A few weeks later, in February 1943, a twenty-three-year-old kibbutznik visited Hannah at Sdot Yam. After months of depression and isolation, Hannah was so thrilled to see Yonah Rosen that she rushed to hug him like a close family member, even though they’d only briefly met two years earlier when she had been touring the north, looking at various kibbutzim. Yonah belonged to the group of young intellectual Hungarians who’d made aliyah in the late 1930s and were building Kibbutz Maagan on the southern shore of the Sea of Galilee.

Two and a half years older than Hannah, born Gyula Rosenfeld in 1919 in the small city of Cluj in the Transylvania region, Yonah was a small, sinewy man with fine features and a winsome smile. He looked almost boyish, Hannah thought, but for the way his thick black hair was already receding high at the crown. Married and the father of a young son, he had enlisted in the Palmach two years earlier and was already a senior commander. Now he confided in Hannah that he was helping to organize a top secret military mission, to rescue the Jews of Hungary, Central Europe, and the Balkans.

Hannah’s eyes opened wide at the mention of Hungary—at the very possibility of return. Yonah explained that he was recruiting volunteers who could speak Hungarian and were familiar with Hungary’s diverse terrain—should the mission be approved, there would ultimately be a designated Hungarian infiltration team. Meanwhile, other Palmach commanders were looking for volunteers fluent in Romanian, Bulgarian, Slovakian, and Croatian. The plan was still hazy and highly confidential, but nine months earlier, the secretariat of Kibbutz Sdot Yam had put forth Hannah’s name as a possible recruit for the elite underground.

She was in peak physical shape. Naturally athletic, an avid tennis player and swimmer back in Budapest, she had grown even leaner and stronger over her years at Nahalal and Sdot Yam. Most important, Yonah said, she had the passion that would make her a perfect candidate for the mission.

“How strangely things work out!” Hannah wrote on February 22, describing her encounter with Yonah but prudently not naming him in her diary. “A few days ago, a man from Kibbutz Maagan, a member of the Palmach, visited the kibbutz. … He told me that a Palmach unit was being organized to do exactly what I felt that I wanted to do. I was truly astounded. The identical idea!”

Hannah told Yonah that of course she was ready—absolutely ready. He cautioned her that the mission was still in the planning stages, but he considered her “admirably suited” for it. “I see the hand of destiny in this just as I did at the time of my aliyah,” she wrote. “I wasn’t master of my fate then, either. I was enthralled by one idea, and it gave me no rest.”

In 1938, while only seventeen, finishing high school in Budapest, Hannah had resolved that she would leave fascist Hungary. She was single-minded and driven, dedicating herself to learning Hebrew, studying Zionism, intent on making aliyah regardless of whatever obstacles stood in her way. Now she again sensed “the excitement of something important and vital ahead . . . the feeling of inevitability connected with a decisive and urgent step.” There was a chance, of course, that the whole idea would “miscarry,” that she’d receive a message informing her that the mission was being postponed or, worse, that Palmach officers more senior than Yonah had judged her not qualified. “But I think I have the capabilities necessary for just this assignment, and I’ll fight for it with all my might.”

In her freezing canvas tent that night, she couldn’t sleep as she visualized returning to wartime Hungary, not as the delicate, demure, bookish schoolgirl Anna Szenes but as a tough, trained Palmach fighter. Yet how would she notify her mother of her arrival? How would she organize the Socialist Zionist youths to either resist or escape, as she had done, to the Land of Israel?

For the next few weeks, she continued preparing herself mentally and physically to become a soldier. Yonah would update her regularly, but he kept saying that progress on the mission was slow. Hannah had little idea that the various branches of British Intelligence, military agencies, civil servants, and politicians were clashing, tying up the mission in bureaucratic gridlock.

The British Middle East Command in Cairo and Churchill’s war cabinet in London were locked in a wide-ranging dispute over the wisdom of arming, training, and thereby legitimizing the Haganah. When war had broken out, with the hated White Paper having dramatically capped Jewish immigration, David Ben-Gurion had fired off his famous epigram: “We must support the British Army as though there were no White Paper; and fight the White Paper as though there were no war.”

It was “a good play on words,” wrote the historian Yehuda Bauer. “In reality, however, the double course was impossible. The line taken by the Jewish Agency—echoed by the Haganah—was that cooperation might prove to the British that the Jews were loyal allies, potentially influencing the many British statesmen uneasy about the White Paper. British military headquarters in the Middle East, on the other hand, regarded the Jews with marked skepticism.”

Yonah also hadn’t had the heart to tell Hannah that the Palmach had encountered stiff resistance from British military authorities about allowing women volunteers to enlist. For the Haganah, gender was never an issue: On the kibbutzim a woman was expected to do everything a man could do, even pick up arms and fight in the defense of the Homeland.

That attitude was not shared by senior military officers or policymakers in 1943. Although Great Britain had 640,000 women in uniform during the Second World War, none was officially allowed in combat. The U.S. armed forces similarly boasted 350,000 women in the services but kept them from the front lines. Among the Allies, only the USSR made full use of approximately 1 million female troops; Soviet women were frontline infantry, combat pilots, aircraft gunners, and, in several notable cases, such as the legendary Lieutenant Lyudmila Pavlichenko, among the most decorated snipers in the Red Army.

The notion of allowing a woman—Jewish or otherwise—to parachute behind enemy lines in uniform seemed ludicrous to the British officials who heard about the Palmach’s proposed rescue mission. If captured by the Germans, they argued, any female in uniform would almost certainly be tortured by the Gestapo and shot as a spy.

Excerpted from Crash of the Heavens: The Remarkable Story of Hannah Senesh and the Only Military Mission to Rescue Europe’s Jews During World War II by Douglas Century. © 2025 and published by Avid Reader Press. Printed with permission of the authors.

Reviews:

“Powerful … Cinematic … Douglas Century’s Crash of the Heavens excavates the brilliant young woman—frustrated, lonely, headstrong, determined—long encrusted in myth. … Her story, told here with great intimacy and detail, is riveting. … A stirring testament to both her undeniable gifts and tragic fate.” — Forward

“Impeccably researched, powerfully told, Crash of the Heavens is a testament to courage, determination and resilience. A story for our times.” — Esther Gilbert, founder and editor, Holocaust Memoir Digest

No responses yet