Princeton Renames Wilson School and Residential College, Citing Former President’s Racism

Princeton’s trustees voted Friday to rename the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs and Wilson College, removing the name of the alumnus and former U.S. and University president whose racist actions have been the subject of a critical reevaluation in recent years. The University’s top honor for an undergraduate alum will continue to be called the Woodrow Wilson Award.

According to announcements released Saturday afternoon, the school is now called the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs. The University also moved up its plan to “retire” the name of Wilson College, the first of its six residential colleges. It is now known as “First College.” The name of the award — conferred each year on Alumni Day — will not be changed because, the trustees wrote, Princeton took on a legal obligation to name the prize for Wilson and to honor his “conviction that education is for ‘use’ and … the high aims expressed in his memorable phrase, ‘Princeton in the Nation’s Service.’”

In a statement, the Board of Trustees said of the Wilson School decision, “We have taken this extraordinary step because we believe that Wilson’s racist thinking and policies make him an inappropriate namesake for a school whose scholars, students, and alumni must be firmly committed to combatting the scourge of racism in all its forms.” The trustees cited the recent killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and Rayshard Brooks as “tragic reminders of the ongoing need for all of us to stand against racism and for equality and justice.”

The changes were recommended by President Eisgruber ’83, who noted in a separate statement that “Wilson’s racism was significant and consequential even by the standards of his own time.” Eisgruber acknowledged that the University’s conclusions “may seem harsh to some. Wilson remade Princeton, converting it from a sleepy college into a great research university. Many of the virtues that distinguish Princeton today — including its research excellence and its preceptorial system — were in significant part the result of Wilson’s leadership. … People will differ about how to weigh Wilson’s achievements and failures. Part of our responsibility as a University is to preserve Wilson’s record in all of its considerable complexity.”

Eisgruber said in his statement: “Wilson is a different figure from, say, John C. Calhoun or Robert E. Lee, whose fame derives from their defenses of the Confederacy and slavery (Lee was often honored for the very purpose of expressing sympathy for segregation and opposition to racial equality). Princeton honored Wilson not because of, but without regard to or perhaps even in ignorance of, his racism.

“That, however, is ultimately the problem. Princeton is part of an America that has too often disregarded, ignored, or excused racism, allowing the persistence of systems that discriminate against Black people. When Derek Chauvin knelt for nearly nine minutes on George Floyd’s neck while bystanders recorded his cruelty, he might have assumed that the system would disregard, ignore, or excuse his conduct, as it had done in response to past complaints against him.”

Read More: Wilson, Revisited (Feb. 13, 2016)

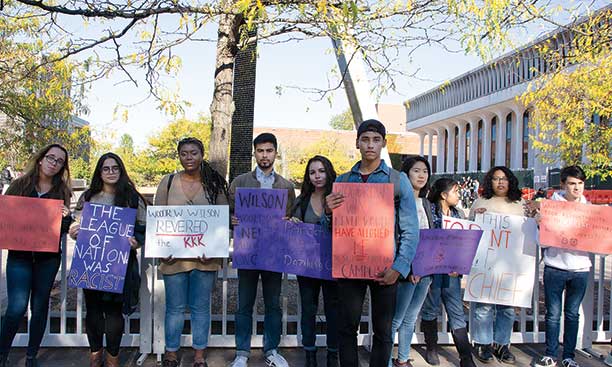

Wilson’s legacy has been a matter of intense debate at Princeton since at least November 2015, after the Black Justice League, a student group, led a 33-hour sit-in at Eisgruber’s office in Nassau Hall. The group’s demands for racial justice included removing Wilson’s name from University buildings and programs, an issue that drew national attention. (The New York Times weighed in with an editorial endorsing the change.) Eisgruber formed the Wilson Legacy Review Committee, a 10-member trustee committee chaired by Brent Henry ’69, to consider whether the University should change the ways in which it recognizes Wilson’s actions at Princeton and during his time in the White House.

Hundreds of alumni shared their views with the Committee, which released its final report in April 2016. While the Committee said the University must be “honest and forthcoming” about its history and recognize Wilson’s failings, it stopped short of recommending renaming the Wilson School or Wilson College. Princeton’s trustees approved several additional actions recommended by the committee, including creating a “pipeline program” to encourage more students from underrepresented groups to pursue doctoral degrees and careers in academia; adding campus art and iconography that reflects Princeton’s diversity; updating the University’s informal motto; and installing a permanent marker near Robertson Hall that “educates the campus community and others about both the positive and negative dimensions of Wilson’s legacy.” The marker, created by artist Walter Hood, was installed in October 2019 and drew new protests and continued debate over Wilson’s racial views.

The issue resurfaced again this month, as the nation grappled with racial injustice. On June 22, a group of students and alumni of the public-affairs school sent a letter to the University administration requesting “comprehensive transformation” of the school. Alumna and philanthropist Kwanza Jones ’93 also wrote an open letter to Eisgruber and Vice President for Advancement Kevin Heaney, arguing that by not removing Wilson’s name, “Princeton seems content on lauding Wilson and glorifying his actions.”

The student and alumni letter, co-authored by Gaby Pollner ’20, Ananya Malhotra ’20, Andrew Gnazzo ’20, and Janette Lu’ 20, included demands to change the core curriculum; hire people of color for faculty positions; institute a senior-thesis prize similar to the Toni Morrison Prize for work that has “pushed the boundaries and enlarged the scope of our understanding of issues of race”; create a committee to research reparations; and denounce and remove Wilson’s name from the school. They also asked for training for all faculty and staff on anti-racism and transparency in cases of discrimination in the classroom.

“[We] are deeply troubled and angered by the School’s silence regarding the ongoing practices of racial injustice and police brutality, particularly in the context of Princeton’s preservation of Woodrow Wilson’s legacy,” the letter said. “We are compelled to write at this … because of Princeton’s culpability in histories of slavery and oppression.”

In addition to the individual signatories, the letter was endorsed by Princeton student groups, including the Black Student Union, Association of Black Women, Black Men’s Association, African Students Association, Students for Prison Education and Reform, the Latin American Student Association, and Black Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson Accountability Task Force.

The Woodrow Wilson School began in 1930 as the School of Public and International Affairs and was renamed in Wilson’s honor in 1948, the same year that the school’s graduate professional program was added.

In a statement to school alumni, Dean Cecilia Rouse wrote that she “unequivocally support[s]” the decision to change the name. “Retiring the name does not take the place of systemic change, but it does signal that we are prepared to do the hard work of confronting racism and other injustices,” she wrote. “We have much more to do, and I know all of you stand ready to contribute your time, thoughtfulness, and passion to that effort.”

Rouse wrote that she is glad the school is no longer named for any individual: “Connecting the School to a certain person signals that the School stands for much of what the honoree believes. I feel that for a policy school to be the best, it has to be a place where a true diversity of backgrounds and beliefs exist,” she said.

Wilson College had its roots in a progressive movement at Princeton. The college grew out of the Woodrow Wilson Lodge, created in 1957 by members of the Class of 1959 as an alternative to bicker and the eating-club system.

Read More: ACLU Director Anthony D. Romero ’87’s 2020 Woodrow Wilson Award Address

As Michael Ellis ’59 wrote in a letter to PAW in 2016, “around half a dozen intrepid sophomores, after a couple of years of especially horrendous bickers, announced to the University that they would refuse to bicker and that they believed the University owed it to them to provide an alternative ‘facility’ for their dining and socializing. In support of this mini-movement, a couple of them did original research in the library of the effort by President Woodrow Wilson [1879] to alter or eliminate the club system. The University, much to our surprise, responded well; and by the fall, the old Madison dining hall of Commons was renovated and made into a comfortable two-room facility with, I recall, excellent meals.” Ellis recalled that Lodge members invited faculty members, including poet and critic R.P. Blackmur and famed physicist John Wheeler, to join students for dinner and informal conversations, “making some memorable evenings.”

In 1961, the Lodge moved to the newly constructed Wilcox Hall and renamed itself the Woodrow Wilson Society, becoming Wilson College in 1968.

52 Responses

John P. Hyde ’59

4 Years AgoWilson and the Peace of Paris

Woodrow Wilson was the enabler, if not the principal architect, of the disastrous 1919 Peace of Paris. The outcome of the war was decided by the 1918 Meuse-Argonne offensive. It consisted of 600,000 American soldiers and, as such, is the largest battle in our history.

The accord consisted of five treaties: Neuilly (Bulgaria), Sevres (Turkey), St. Germain (Austria), Trianon (Hungary), and Versailles (Germany). The Treaty of Versailles was signed in the same Hall of Mirrors where the German Empire was proclaimed 48 years earlier. Imagine if the British had won the War of 1812 and we had to sign the treaty in Independence Hall!

Henry Kissinger called the Congress of Vienna “a world restored.” The Peace of Paris was a world ripped apart. It sowed the seeds of World War II and its consequences are felt to this day. It is ironic that Wilson’s name used to be on our school of international relations.

The son of the Virginian minister was in over his head. Frederick the Great was right when he observed, “It is a long way from the Ohio River to the Spree.”

Gary R. Walters ’64 *75

5 Years AgoBeing Mestizo

A lot of time spent recently in Peru and Columbia reveals a very different assimilation of native people and people of colour. Most everyone is mestizo (of mized race). After the Spanish invasions, the decimation of populations from European diseases, the extensive use of slave labor, native and Black, cruel and abusive treatment — it did not prevent an intermixture of the races. Intermarriage is such that in most areas there is not only literal relationship, but also a shared understanding of culture, history, and experience. There was no stark separation of white and Black such as came to pass in the U.S. For quite a while the Spanish attempted to maintain a purity of blood. There are still echoes of this. There is still a longing to be white in many people. But the satisfaction of family life predominates. When asked about their history and racism and oppression, the answer is not loaded with anger and resentment. But they say yes there is discrimination. And certainly the economic inheritance has put these people at the bottom of the ladder for the most part. But they are patient.

So from what I have observed there is no embedded functioning racism. Is it that these people, all intermingled, mostly devout in their catholic faith, inheritors of extraordinary creative traditions, habits of living together — is it that they have not had to endure or answer to the shibboleths of white protestant America, the terrible fierce distinctions of right and wrong?

And then the people were not divided into North and South. Canada, by the way where I live, could not use slave labor in its agricultural endeavours. But its treatment of native people has been and continues to be appalling.

So there has been a very different evolution in the colonial conquest and usurpation in North and South America. The eventual easy intermingling of the races over time in South America obscured and then diminished the difference literally and symbolically of different coloured skin.

Industrialization and independence was slower to come as well. The difficulties of survival were for the most part shared in lives that continued to be for the most part agricultural. In a very general sense the patterns established in Pre-Colombian America continued and still do. People still regularly go to a doctor and to a shaman.

I can still hear my father’s voice condemning a mixed race couple when we lived in Chicago 50 years ago. I remember my confusion. “Well what’s wrong with that?” I asked him. My schoolmates there were predominantly Black and frankly I much preferred their company.

Charles S. Rockey Jr. ’57

5 Years AgoWilson’s Party

The Princeton Alumni Weekly of September 2020 has several articles and references to Woodrow Wilson 1879. None, however, identify Wilson as a Democrat. Almost all of the Southern Democrats of his day were segregationists and racists.

This continued long into the 20th century. Most Southern Democrats in the Senate and House voted against the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Jean-Pierre Cauvin ’57 *68

5 Years AgoHistory as ‘More or Less Gray’

Anent the ever-contentious Woodrow Wilson issue, one is reminded of the observation spoken by Marc Antony in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar: “The evil that men do lives after them. The good is oft interred with their bones.”

The reverse of this dichotomy obtained until the recent reevaluation and determination. We should no more bury Wilson’s positive achievements than we should forgive and forget his reprehensible actions. (In fact, doesn’t that hold true for all of us?)

The problem with cancel culture lies in the meaning one gives to “cancel.” Eliminate altogether? Or start afresh and reassess with maximum fairness and objectivity? As French historian André Kaspi wrote: “History is never all black or all white. It is always more or less gray.”

Charlie Bell ’76

5 Years AgoWhat Would Woodrow Do?

If Woodrow Wilson were alive today and facing the same choice that President Eisgruber and the Board faced, what do we suppose his decision might be?

I suspect that as a visionary, progressive leader in almost every way — a man whose life was informed by the past yet inspired by his dreams of the future — Wilson would consider the choice an easy one. Or at least a clear one.

Norman Ravitch *62

5 Years AgoWhat Would Woodrow Do?

What would Woodrow do if he were here today? Based on his record at Princeton, as well as in Washington, D.C., and at the Paris Peace Conference, I believe his messiah complex and his odd relationship with God his father (his real father, not the man in the skies) would have made him furious at being challenged, self-righteous as he always was, and possibly emotionally and mentally disabled by criticism. To think he could act rationally and sensibly is not to encounter the real Wilson, unfortunately.

Laurence C. Day ’55

5 Years AgoWith Wilson, It Was More Than Racism

The racist slant emerged to remove rightly Wilson’s name from the School of Public and International Affairs and the residential college. Yet from the outset and inception, his name should never have graced either. As President, Wilson lacked strong liberal Presidential leadership. Elected with only 42 percent of the popular vote in 1912 due to the divided Republican and Progressive tickets, he further scraped by to defeat Republican Charles Evans Hughes by a narrow electoral college margin and popular vote in 1916. He did not use his public pulpit to entreat and turn the heads of the German and Irish population and peacenik isolationists to join in a patriotic conflict raging in Europe bringing the country together to demand the nation enter the war on the allied side until it was inevitable in 1917.

Yet, once committed with a draft of men and opposition to it and entering the rising war in France, Wilson was instrumental in supporting the most horrendous and devious assault on free speech, a free press, and civil rights with the Espionage Act and the Sedition Act of 1918 since the Alien and Sedition Act of 1789.

The Supreme Court upheld wrongly the convictions in the Charles Schenck and Eugene Debs, 1919 cases highlighted by Justice Holmes under the “clear and present danger” rubric; yet, with a change of heart, Holmes reversed his own doctrine to state that speech could be curtailed only if it represented an “imminent and immediate” threat to violence in his dissent in the soon later Abrams case. The irony today is the University supports broad free speech expression as Holmes declared in that Abrams dissent. The background on these Supreme Court cases I comment upon because Wilson agreed with the Court's decisions as he refused to free Eugene Debs from incarceration in prison. Ironically, the less-than-majestic President Harding did free Debs a few years later.

And the notorious warrantless Palmer raids (A. Mitchell Palmer, Wilson’s attorney general) — arrests, convictions, incarcerations, poor Russian immigrants’ wholesale deportations, all without hearings or trials — were the utter worst violations of civil rights and freedom of speech we’ve had to endure. That was under Wilson’s presidency.

Wilson’s first choice for the Supreme Court was Southerner James C. McReynolds, who became one of the most backward, rude, radical, illiberal, and obstreperous justices ever on FDR’s court. That choice was somewhat reprieved by his choices of progressive liberals Louis Brandeis and John Clarke. But his choice of McReynolds castigates Wilson from the outset.

Yes, Wilson’s conception of the League of Nations was ahead of his time. But as intractable, rigid, and self-serving as Wilson was, he torpedoed the vote to affirm the League in the negative vote by Congress. A former British Prime Minister made a special trip to Washington to plead with Wilson to accept the compromise on our nation’s sovereignty in the League with his adamant Republican Senate foe Henry Cabot Lodge. Wilson would not even deign to meet this emissary. He defied any modest compromise with Lodge; both hated each other, and the League was doomed in this country.

Thus, Wilson, wracked with illnesses and depressions as president, ineffectual for months, a willing scourge to our basic Bill of Rights in free speech, a free press, and basic civil rights, Wilson acted more the stern Presbyterian elder lecturing strict morality and the wrath of God, the social historian Sinclair Lewis’ Elmer Gantry in sheep’s clothing.

No, it is not the specter of just racism, which is the tip of the Wilson legacy iceberg as president. All reason enough to remove his name from the Princeton scoreboard.

Yet, the opportunity to name the school in place of Wilson was apparently overlooked. But President Eisgruber and the Wilson Committee can now do real justice to that school and name it the George F. Kennan School of Public and International Affairs. The greatest American diplomat in the 20th Century bar none. He named it the “cold war” and he held in check our ignorant bombastic statesmen and military chiefs, many of whom wanted be the first aggressor to bomb Russia to death and so destroy ourselves in the process with a Third World War.

And while they are about it, name a lecture hall in the school after the other brilliant patriot who stopped the invasion of Japan and was done dirt later by the Gray Committee and the AEC and the horrid Lewis Strauss — name it after the magnificent physicist and Director of Los Alamos and the Princeton Institute for Advanced Study, Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer.

Norman Ravitch *62

5 Years AgoWhat to Name Buildings and Monuments

Since history is not what happened in the past but what scholars and others in any given generation wanted to think about the past, any name given to a building or monument could be changed every so often by politics and ideology. Just look at Tsarist Russia, Red Russia, Putin’s Russia. Just look at Germany: the Germany of Bismarck, the Germany of Weimar, the Germany of Hitler, and so on. Perhaps buildings and monuments should, like public schools below high schools in many cities like New York City, should simply get numbers. I went to elementary school in my youth in public schools 164 and 34 and have never had to apologize. I did go to high school at Andrew Jackson and were I politically correct would have to apologize I suppose, but I won’t.

Andrea M. Matthews ’78

5 Years AgoAt Last

I grew up, like many progressive Northerners, to think that Woodrow Wilson’s fight to establish a League of Nations was a noble cause. As a Princetonian, I was proud that he’d been at the head of the University, and helmed the country during World War I. Like so many Americans, I was fed a white-washed lie, and I uncritically swallowed it. The man was an intellectual and academic fraud, and a monster who rolled back progress in this country, costing countless lives and livelihoods, and a century of further progress that might have been. Even his great “vision” for the League was a fraud — he was in fact attempting to impose the same white-supremacist apartheid and virulent racism on the world that he had re-instituted and expanded in our government and in our country. It’s time to stop pretending that statues and named buildings and schools are not honorific in nature. Put Wilson and his ilk back in the classroom for honest discussion, and take their names and images off the places we look up to.

There are any number of books and articles one might read to be enlightened, but if you have any doubt whatsoever about the propriety, the urgency, the absolute necessity of the University’s belated but welcome action, I would urge you to read Colin Woodard’s Union: The Struggle to Forge the Story of United States Nationhood. If you are not filled with rage and shame at the career of our fellow alumnus and former president, I believe Princeton will have failed in the nation’s service and in the service of the world.

Joe Illick ’56

5 Years AgoOn Respectful Listening and Change

I can see no reason to doubt that President Eisgruber ’83 and his advisers thought long and hard about the decision to disassociate Woodrow Wilson’s name from Princeton (On the Campus, September issue). That Wilson’s blatant racism was unimportant to decision-makers at the University generations ago should not bind us to their judgment now. As we recognize how fragile our democracy has become, we must be vigilant in our care for the rights of all citizens.

Paying respectful attention to every American translates not to dismissing the aspirations of some as “current fashion” or “social trends” but listening to what others have to say and taking them seriously. I learned this while working in an experimental division of my college, a white teacher with Black — and only Black — students. Forced to listen, I learned lessons I had previously denied myself. It was humbling and, I like to think, broadening.

When I arrived at Princeton in 1952, I found the University’s enchantment with tradition strange and intimidating. But in the classroom my ideas, even if immature or poorly stated, got an audience, and that truly mattered. Princeton has changed in many positive ways since then, as indeed it was altered — by Wilson as much as anyone — in important ways since my grandfather was in the Seminary at the turn of the 20th century. If it is now more responsive to its students, that is a sign of its strength as a democratic institution. That ought to be a cause for optimism among its alumni.

John Brittain ’59

5 Years AgoFlippant Cover Line

The flippant headline, “Goodbye, Woody Woo,” on the September PAW cover is tasteless and offensive in the context of the concern over the question of Woodrow Wilson’s name. I disagree with the decision to remove it, as it implies that, in Wilson’s life, regardless of his achievements, the most important question about his life is whether he liked Black people or not. He was a man of his time, and I would guess that a majority of the American population then was also racist. Does your decision thus imply that we should get out our family picture albums and remove grandfathers and uncles?

Regarding the decision to signal that the University condemns racism: I should have hoped this was evident already. I expect that this action will have little resonance with Black people in general, who have better things to worry about than intellectual debates in the Ivy League. If you were seriously interested in improving the lives of Black people, you would urge your students to advocate for the destruction of the power of the teachers’ unions that restrict the ability of Black families to choose schools that they prefer for their children. Absent this, all your posturing over names is nothing but an irrelevant charade.

However, as long as symbols are important to you, I suggest you deal with the tiger, who seems an overly masculine and aggressive personification for a university that is mostly feminine and compassionate. How about a dove instead, or perhaps a chicken?

Rocky Semmes ’79

5 Years AgoTiger Traits

John Brittain ’59’s knickers-in-a knot letter over the Wilson School renaming (Inbox, November issue) somehow collapsed into a curious cacophony about totemism comparing masculine and feminine characteristics, childishly suggesting aggression as naturally superior to compassion. Mr. Brittain clearly considers his argument brave and bold but it is basically full of baloney being all blather, bluff, and braggadocio with no bite. Mr. Brittain offers the tiger as a personification of what to him is clearly preferred masculine character. He seems to be forgetting the female tiger who when defending her cubs is the more aggressive of the two tiger genders. This fundamental oversight by Mr. Brittain clearly labels him a member of the old school, so to speak, and so we must excuse his inevitable error.

James B. Fletcher ’54

5 Years AgoRemoving Wilson’s Name

It is significant to me that those who won recent advancements in American social issues all had skin in the game. The trade union fights, women’s suffrage, Cezar Chavez, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the “Me Too” movement. All took considerable personal effort and risk to gain their ground. Removing Wilson’s name accomplishes nothing substantial and presents no risk to a group of students and faculty all safely removed from anything gritty.

J.W. Donner ’49

5 Years AgoExample of Presentism

Princeton’s decision to cancel out Woodrow Wilson’s honored memory is both wrong and a cowardly example of presentism. This is the nut of my strong complaint. I am matching words with action: This lifetime active and loyal alumnus, as well as father to Alex Donner (’75), is removing Princeton from his will just as Woodrow Wilson is now removed from what was “the best old place of all.”

Richard W. Corkhill ’53

5 Years AgoWilson’s ‘Body of Work’

I was appalled at the University’s decision to remove Wilson from multiple places at Princeton. We all recognize his racist stance but we also recognize his many contributions to Princeton, New Jersey, the United States, and to the world. As they say in the entertainment business, judge by the “total body of work.” You can’t pluck an individual out of history and judge him/her by the customs, values, and mores of another time. As I write this, the statue topplers are after Columbus and Teddy Roosevelt. I suppose the Jefferson Memorial and the Washington Monument are next. God help us if a historian decides that St. Paul was assisted by a slave on the road to Damascus.

Richard Schimel ’75

5 Years AgoPrinceton’s Early Presidents

President Eisgruber’s June 27 Message to the Princeton Community concerning the renaming of the Woodrow Wilson School of International Affairs and Wilson College will undoubtedly prompt discussion among students and alumni. But a building is no more than brick and mortar or concrete. What is essential is how we modify our attitudes and our behavior towards humanity. Princeton has been making substantial efforts to combat implicit and explicit racial bias on campus, and I am hopeful that this trend will continue. I applaud the efforts of Princeton University to create a more just environment on campus.

I support changing the name of two buildings on campus to eliminate the visual abuse that they have caused. Does it end here? Just how far should Princeton go to remove the names of past Princeton presidents who contributed to the growth and success of Old Nassau, but who were racially biased? I do not pretend to know the answer to that question. But what I can do is relate the early history of our university’s first eight presidents, courtesy of the Princeton & Slavery Project website, found at https://slavery.princeton.edu/stories/slaveholding-presidents. There you will find the information summarized below.

Reverend Jonathan Dickinson was the first president of the College of New Jersey. The hall housing the Department of History bears his name. In June 1733, Dickinson purchased an enslaved girl named Genny from a neighbor. Slavery remained central to Dickinson’s worldview throughout his career in the pulpit. From “Princeton’s Founding Trustees” by Michael R. Glass.

Reverend Aaron Burr Sr. served as the second president of the College of New Jersey, from 1748 to 1757. In 1756, Burr oversaw the college’s move to its new Princeton campus—which at the time consisted only of Nassau Hall (built on land donated by a wealthy slaveholder), and the President’s House. That same year, Burr purchased an enslaved man named Caesar for eighty pounds. Caesar was not Burr’s only slave, however. When Burr died in office in 1757, he left a will that listed three enslaved people assessed at a monetary value of 150 pounds. From “Aaron Burr Sr.” by Shelby Lohr.

In 1757, Jonathan Edwards succeeded his recently deceased son-in-law, Aaron Burr Sr., as its third president. Edwards and his wife Sarah had eleven children. He maintained the large household in part through the labor of enslaved people. In 1731, Edwards visited Newport, Rhode Island, where he purchased Venus, a “Negro girl” estimated to be 14 years old. Records also indicate that Edwards owned a “Negro boy,” Titus, and a second female slave named Leah—although historians are uncertain as to whether the family simply gave Venus a biblical name. From “Jonathan Edwards, Sr.” by Richard Anderson.

Samuel Davies was the College of New Jersey’s fourth president. Davies was particularly interested in ministering to slaves. He championed literacy for enslaved people and seemed deeply committed to their spiritual welfare. However, he never questioned the legitimacy of human bondage and owned slaves himself in Virginia. From “Presbyterians and Slavery” by James Moorehead.

Samuel Finley was unanimously elected the college’s fifth president in 1761, after the death of Samuel Davies. While serving as president, Samuel Finley owned slaves, at least six of whom lived and worked at the President’s House on campus. At the time of his death in 1766, Finley’s estate included “Two Negro women, a negro man, and three Negro children.” A public notice advertising the sale of the late president’s property stated that the enslaved women were conversant in “all kinds of house work,” with the men trained in farming and agricultural work. In August 1766, these enslaved people were sold alongside furniture, livestock, and “books, religious, moral and historical.” The auction was advertised to take place at the President’s House on campus. From “Samuel Finley” by Shelby Lohr and R. Isabela Morales.

John Witherspoon was Princeton’s sixth president. Though he advocated revolutionary ideals of liberty and personally tutored several free Africans and African Americans in Princeton, he himself owned slaves and both lectured and voted against the abolition of slavery in New Jersey. From “John Witherspoon” by Lesa Redmond.

Samuel Stanhope Smith studied under President Witherspoon and returned to Princeton as a professor in 1779, and succeeded Witherspoon as its seventh president in 1795. We know from a 1784 newspaper advertisement that Smith owned at least one slave during his time at Princeton, a farm hand whom Smith was keen to exchange for another slave “accustomed to cooking and waiting in a genteel family.” This preference for house slaves made its way into Smith’s Essay. There was, he insisted, a “great difference” between the facial features of “domestic and field slaves.” House slaves soon began to resemble their masters, both in their features and their conduct. This gave Smith hope that, if “admitted to a liberal participation of the society, rank and privileges of their masters, they would change their African peculiarities much faster.” Smith never abandoned the belief that white people stood at the apex of human society. He insisted that African Americans and Native Americans could become white if placed in different environments, or after intermarriage with whites. From “Samuel Stanhope Smith” by Nicholas Guyatt.

In 1812, Princeton’s Board of Trustees unanimously elected Ashbel Green as the eighth president of the college. Ashbel Green’s “servant” John was one of three slaves who lived and worked at the President’s House (later called the Maclean House) while Green was president. In June 1813, eight months after moving to Princeton, Green wrote in his diary that he had “purchased the time of a black boy and black girl” from the executors of a recently deceased woman’s estate. The boy, John, was twelve years old at the time, and the girl, Phoebe, was nearly eighteen. Although he considered slavery an evil practice, Green did not believe immediate and universal emancipation would be either practical or beneficial—writing instead that uneducated, irreligious slaves would only “destroy themselves or others” if emancipated before they were prepared to exercise freedom. Green further believed that emancipated slaves and free-born African Americans would fare better in “the land of their ancestors” than in the United States. From “Ashbel Green” by R. Isabela Morales.

The ancient Romans issued government decrees known as damnatio memoriae in an attempt to destroy visual depictions of emperors or public figures from inscriptions, portraits, and coins bearing their image. In like manner, should we change the names of Dickinson Hall, Edwards Hall, and Witherspoon Hall? Should we move portraits of these past Princeton Presidents from the Faculty Room of Nassau Hall (designed, incidentally, by Woodrow Wilson) to a less prominent location? Are these other former University presidents deserving of the legacy of visual immortality, although they did not believe in racial equality? Do we continue to venerate their achievements, despite their support of the institution of slavery?

Before Princeton University goes down such a path, it should consider an additional idea. Perhaps it is time for Princeton to render to Caesar, and all other former slaves of Princeton presidents, and those that have experienced the burdens of discrimination at Princeton that which is due. Betsey Stockton was born into slavery in Princeton at the end of the 18th century. She worked in the home of Ashbel Green. After gaining her freedom, she established a missionary school for native Hawaiian children. She later started a school for Black children in Philadelphia and taught for 30 years in the only public school in Princeton for African American children. (The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, May 2, 2018.) One can read the full story of Betsey Stockton at https://slavery.princeton.edu/stories/betsey-stockton.

In the June 24, 2020 issue of the Princeton Alumni Weekly one finds the following: “In 2018, the Board of trustees of Princeton University voted to name a new green roof garden at the Firestone Library in her honor. In 2018, the University planted a garden between Firestone Library and Nassau Street to honor Betsey Stockton. The grasses and flowering plants serve as a green roof for the library’s B and C floors.” This is a promising development.

Norman Ravitch *62

5 Years AgoA Tempest But Not in a Teapot

The great response on both sides of the Woodrow Wilson issue demonstrates that the issue is not simply about one American president and Princeton academic star. It is about political correctness, which today takes a variety of forms: charges of racism by leftists who see all moderates as racist; a malady in seeing our history as only oppressive; a wildly naive view of racial and ethnic problems which are not solved by slogans and counter-prejudice; a lack of respect for dissenters of different sorts; and in rare cases anarchism and terrorism.

Princeton might have been a force, albeit a small one, for reason. Under President Eisgruber, it has become an anti-force for compliance with ignorance and passionate stupidity.

Bob Hazard ’56

5 Years AgoWilson Is Not Alone

Congratulations to Princeton, which, like many of our educational institutions, has succumbed to the not-so irrational fear of being branded as “racist.” The trustees concluded that “Woodrow Wilson’s racist thinking and policies make him an inappropriate namesake for a school or college … This University and its school of public and international affairs must stand clearly and firmly for equality and justice. The school will now be known as ‘The Princeton School of Public and International Affairs.’”

Woodrow Wilson served two terms as president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. He has regularly been ranked by historians as one of our greatest presidents. He led the nation through the first great World War (1914-1918); created and championed the first global concept for resolution of international disputes — the League of Nations, forerunner to the United Nations; received the 1919 Nobel Peace Prize; worked tirelessly to get the U.S. to join the League (1918-1924); and added the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, giving women the right to vote. These mammoth accomplishments have since been “whitewashed” by allegations that he was a proponent of segregation.

Wilson is not alone. Racist charges have been heaped on the Father of our Country, George Washington (slave ownership); Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence (slave ownership); Andrew Jackson, Old Hickory and a populist president (slave ownership); Teddy Roosevelt (racist); Christopher Columbus, who never set foot on U.S. soil (racist).

Falsely charged of racism are Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, and Frederick Douglass, the ardent abolitionist. Even Francis Scott Key, who authored the Star-Spangled Banner, has been tagged as a racist. There are calls for a new National Anthem. Perhaps we could replace the words “Oh say can you see” with a more inclusive message, like “Oh say can we take a knee“ to show our distain for America and its flag.

Omitted from this hysteric clamor for progressive political correctness is FDR, who marched all those U.S. Japanese off to prison camps. Also exempt is civil-rights champion Lyndon Johnson, whose relationships with Black people were marred by his Southern prejudices. According to his chauffer, Robert Parker, Johnson consistently addressed him with racial epithets.

As a 1956 graduate of the Princeton Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, I find it puzzling that Wilson School alumni were not polled before erasing the name. Was it feared that graduates are racist and can’t be trusted to do the right thing?

Charles Scribner III ’73 *77

5 Years AgoAn Elegant Solution

I applaud the decision to rename the Wilson School and I write this as a member of the family and house that published Wilson in his lifetime, and as a tyro publisher four decades ago who commissioned the (very sympathetic) biography of Woodrow Wilson by August Heckscher, which we published 30 years ago and which many rightly consider still the finest biography of that great (if flawed) man. Renaming the Wilson School the “Princeton School” is an elegant and brilliant solution to the controversy since Princeton is a platinum name that eclipses all individuals. (I guess Harvard had the same idea for its medical, business, and law schools?)

Bravissimi!

William Hannum ’54

5 Years AgoOppose Racism Through Actions

On June 27, President Eisgruber announced that the name Woodrow Wilson is being removed from one of Princeton’s colleges and from the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, as a means of opposing racism. This is a cowardly act in response to a mob, and will do nothing to oppose racism. The residual racism in the country will be eliminated by creating opportunities for the less fortunate, not by

bowing to petty demands. Opportunity begins with civil order. Safety, security, and public order are the most valuable products a government can provide; far more valuable than all the public welfare benefits and symbolic actions. Public order is true reparation.

When I was an undergraduate, Woodrow Wilson was revered for his dream of a world governed by an elite collection of intellectuals. His racism was part of his disdain for those less “intellectual” than himself. What is viewed as systemic racism is the tendency to associate lower academic achievement with minorities. This elitism is what Princeton should disavow. The cure to this form of racism is broadened educational opportunity, and an honest respect for those who are not “intellectuals.”

Ken Buck ’81

5 Years AgoProgressives and the War on History

The following submission from Rep. Ken Buck ’81, R-Colo., was originally published by National Review. It is reproduced here with permission from the author.

Princeton University’s decision to remove the name “Woodrow Wilson” from its School of Public and International Affairs is a big win for progressive activists, and the implications will extend far beyond the campus.

It hardly surprises me, in today’s polarizing environment, that my alma mater caved to pressure from radical progressives. What is surprising, however, is that the school caved now, after resolutely standing against the pressure for so many years.

Five years ago, as part of a broader nationwide effort to rewrite American history, Princeton students mounted a campaign to remove President Woodrow Wilson’s name from the school due to his racist views and his efforts to prevent the enrollment of black students. In response, the Board of Trustees formed a committee to review the matter. The following year, the board released a report detailing how to handle President Wilson’s legacy.

The 2016 report drew this important conclusion: “the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs and Woodrow Wilson College should retain their current names and … the University needs to be honest and forthcoming about its history. This requires transparency in recognizing Wilson’s failings and shortcomings as well as the visions and achievements that led to the naming of the school and the college in the first place.”

How refreshing — a recognition that the school should be “honest and forthcoming about its history,” and employ a sophisticated approach to reconciling Wilson’s moral failings with his accomplishments for the University.

Princeton’s own statement tacitly acknowledges the key factor here. It was not the name “Woodrow Wilson” that was under attack; history itself was the target. As we see across the nation, progressives now use Alinsky tactics on history itself. Saul Alinsky’s formula of “picking a target, freezing it, personalizing it, and finally polarizing it” is no longer reserved for living people; historical figures and even episodes in history receive the Alinsky treatment.

Back in 1852, Daniel Webster delivered a speech to the New York Historical Society, on the importance and “dignity” of history. “The dignity of history,” he orated, “consists in reciting events with truth and accuracy.” History is unapologetic in its presentation of facts. History demands that we examine facts and incidents that make us uncomfortable. That challenges us. That inspires us. That serves as a call to action for our lives. The liberal pressure campaign is not about progress, rather, it is an attempt to erase parts of history they do not like. This is a slippery slope, as many liberal activists are even attempting to tear down statues of Abraham Lincoln, the president who ushered in the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing slaves.

History, it turns out, is little concerned with our comfort level.

In the speech, Webster also explained that history’s main purpose is “to illustrate the general progress of society.” History and progress are inextricably linked. History tells the story of progress, and progress is possible by studying history — and, in some cases, learning from past mistakes.

What the Princeton incident reminds us of, however, is how little progressives care for progress. They are unable to recognize the progress the University has made, which the school noted in its 2016 report, in rejecting Wilson’s racist policies and championing the enrollment of black students. Former First Lady, Michelle Obama, a Princeton graduate, frequently cites her experience at Princeton as an empowering opportunity — one that was possible only through the school’s progress.

How do we celebrate America’s accomplishments if we do not acknowledge where we started?

The Princeton name change is part of a larger movement of destruction. As Americans watch in horror and disbelief as statues, national monuments, and even war memorials are removed and defaced, we are left to wonder: What is the end goal of all of this destruction? When will it stop?

Elihu Yale, an early benefactor of Yale University, actively participated in trading slaves, including purchasing and shipping slaves to the English colony of St. Helena. American universities are littered with this type of racism: William Marsh Rice, the Lowell family of Boston, Thomas Jefferson, and Jesuit priests in Maryland all used the profits derived from slave labor to build some of the most prestigious universities in the country. Will tearing down these institutions achieve progressives’ goal?

Moreover, will changing a college’s name or removing the statue of a Founding Father change a Klansman’s deeply held racist beliefs? Will erasing certain books and movies from our public lexicon truly change the hate in someone’s soul? These changes may appease progressives for now, but their goal is much larger.

In my forthcoming book, The Capitol of Freedom: Restoring American Greatness, I explore this very topic. Progressives are determined to destroy not just statues, but historical memories, because they know American history is incompatible with their goals. America’s founding documents, and even the stories behind the statues in the U.S. Capitol building tell the story of American greatness and offer a roadmap for us to renew our commitment to our founding principles.

Slavery is a dreadful part of our history. Despite what progressives say, the abolition of slavery occurred because of, not in spite of, our history and foundation. A nation that was formed with liberty as the chief objective of government was on the right path. The 19th century improved what the 18th century got horribly wrong and the 20th century continued to build upon the 19th century’s advancements. With each century that passes, we move toward a more perfect union. That is progress.

From its founding, our nation’s history is the story of individual freedom and personal responsibility, with limited government as a means for accomplishing both. Our Constitution simultaneously protects individual liberty and thwarts the progressive agenda. Progressives are constantly frustrated in their attempts to remake America into a socialist and godless society because of our Constitution. Is it any wonder that they devote so much of their energy to undermining, subverting, and circumventing the Constitution?

Progressives know that what can be erased can be replaced. Knocking down statues and removing names of institutions are the necessary first step in reshaping America’s future.

For Americans hoping to stop the progressives’ destruction, Princeton provides the answer. No, not the Princeton of 2020 with its disappointing decision to abandon Woodrow Wilson’s name, but the Princeton of 2016 that recognized the importance of being truthful about our history.

In our fight against the progressive agenda, our history is not only what we seek to protect — it is also our primary weapon.

Paul Firstenberg ’55

5 Years AgoThe Board’s Obligation

The decision of the Princeton Board of Trustees to remove Woodrow Wilson’s name from the school after many decades is an unfortunate instance of the Board failing to exhibit some backbone in order to placate short term passions on the campus. A better model for the board is the response of the Chancellor of Oxford when confronted by Black Rhodes scholars pressing for the removal of Rhodes’ statue on the grounds that Rhodes was a racist. The Chancellor rejected the request saying, “Our history is not a blank page on which we can write our own version of what it should have been according to contemporary views. If we remove the Rhodes statue on the premise he wasn’t perfect, where would we stop?”

There is a substantial record of Wilson’s contribution to our country’s domestic reforms and international peace, certainly enough to justify earlier boards naming the school after him. This board has now indulged itself in retroactive judgment-making to satisfy current fashion. I reject this form of revisionism — it will change nothing but surely disturbs the many Wilson School graduates like myself who have for years been proud of the association with Wilson and have no intention of modifying our CVs to placate current whim.

Daniel I. A. Cohen ’67

5 Years AgoOn Associations and Renaming

Paul Firstenberg ’55 wrote in the September 2020 Inbox that he was disturbed at the name change of the Wilson School because he’s been proud of “the association with Wilson.” To what association is he alluding? One doesn’t associate with a dead man by coopting his name. We in New York do not feel associated with the Duke of York — any Duke of York. Eating a Baby Ruth candy bar will not deceive anybody into thinking you’re a better baseball player — no matter who it’s named after. Even a Tesla car runs on direct current. Instead of attempting to bask in another’s reputation for greatness it would be better to achieve some oneself — especially since, as we see, reputation reflects uncertainly.

Mimi Stokes (formerly Katzenbach) ’76

5 Years AgoSymbolic Gestures and the Need for Change

Were he still alive, your esteemed alumnus, my father, former U.S. Attorney General Nicholas de B. Katzenbach, would have noted the decision to remove the name “Woodrow Wilson” from the Princeton School for Public and International Affairs with a combination of recognition of the importance of the gesture, and concern that symbolic gestures by whites are never enough to fulfill the democratic standard to which he held himself, and all whites, in the ongoing struggle for racial equality and justice for all.

He believed it was the civic responsibility of whites to use our white privilege to redress the long sin of 400 years of slavery, and make Black Lives Matter. Democracy demanded nothing less from us. A practical realist, he also believed that the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act would only work long term if whites tirelessly enforced them. Recent horrific events have proved his pragmatic realism tragically correct.

The son of an educator, he would have hoped that those same horrific events would inspire Princeton to take the curriculum changes and commitment to authentic racial (and gender) equity in faculty and students, already underway, deeper and further, till the work of healing this nation, and earning the right to call ourselves a democracy, is, finally, done.

Chester S. Logan ’51

5 Years AgoSeeking More Information About the Wilson Decision

Although the trustees must have observed due process in the matter, it looks like a summary execution. I admit that I have not made it my business to know more about Wilson’s tenure at Princeton and will try to make up for that soon. The trustees did not provide much to the public either.

We cannot erase history with a committee vote or the swipe of a pen. Wilson was a real person who presided over Princeton at a difficult time in history. I hope the trustees intend to give us more information about Wilson and their decision.

Editor’s note: A story about scholars’ views of Wilson’s legacy was published in PAW’s Feb. 3, 2016, issue. Click here to read more.

David Nimick ’46

5 Years AgoA ‘Lasting Memorial’

Earlier this year, I was gifted a copy of The Best of the PAW, a hard cover book published in 2000.

J.I. Merritt ’66, its editor, along with his selection committee did a splendid job in “compiling articles on the history, culture, and traditions of Princeton University.”

As one alumnus (amongst many, I would think) who does not approve of the recent decision to de-Wilsonize the School of Public and International Affairs, I submit what is printed on Page 223, from a May 9, 1947, article on the naming of the school:

… Top priority has been assigned by Princeton University’s Third Century Fund Committee to the financial objective of an enlarged and strengthened School of Public and International Affairs, which will be named as a lasting memorial to President Woodrow Wilson. …

A “lasting memorial” should be lasting! Princeton trustees should take note!

It worries me that the current taking away/destroying/removing past memorials could be enlarged to removing more memorial statues and plaques, names on sports trophies, buildings et al of men/women who later in life displease some citizens for some reason having nothing to do with his/her name being engraved on the physical item.

Richard L. Hames *67

5 Years AgoOn Eliminating Historical Figures

As a former graduate student of the Woodrow Wilson School, I am concerned with the action to remove Woodrow Wilson’s name. I remember Wilson as a president, Nobel Prize winner, and one who promoted free trade, democracy, and human rights. As noted, Wilson remade Princeton into a great research institution. It appears to me the Board of Trustees has succumbed to the current left-wing cultural revolution against traditional American values. This includes the destruction or proposed destruction of statues of our founding fathers, many of whom were slave owners (a common practice at that time that eventually led to the Civil War). As noted by Baher Iskander in his Wall Street Journal article of July 7, 2020:

“While I recognize the importance of challenging simple narratives of heroism, equally simplistic stories of villainy are no better. Erasing Wilson’s name and taking down his large photograph from Princeton’s dining hall evinces an unjustified sense of self-righteous certitude.”

The removal of Wilson’s name does not enhance the reputation of Princeton but rather shows that it is an active participant with those who focus only on eliminating the great historical figures of America.

Tony Tolles ’73

5 Years AgoWhere Princeton Is, Where It Is Going

I am very happy Princeton made the decision to remove Woodrow Wilson’s name to some degree. However, I am disappointed that Princeton decided in could not rename the Woodrow Wilson Award, Princeton’s most important undergraduate honor, because it was a gift. (Can’t we give it back? Why not re-gift it to Yale?)

Princeton should aggressively attack systemic racism — and sexism. I expect the number of deaths from domestic violence far exceed the number of individuals who are murdered by police. Women in our society (including I expect those at Princeton) are systematically subject to sexual discrimination, harassment, and sexual assault. Any meaningful attempt to correct these horrible systemic plagues should include both.

Let’s keep score on where Princeton is and where it is going by annually publishing actual numbers by race (African American, Asian, Latino, Native American, Other and White) and sex. I suggest:

I close with observations about Native Americans. As with African Americans, their story also lasts for 400 years. Our national policy has gone from genocide to apartheid as we trap them in horrific conditions on reservations.

Mark I. Davies ’65 *71

5 Years AgoImperfect Leaders

I have recently learned that Princeton intends to remove the name of Woodrow Wilson from its School of Public and International Affairs, and wish to express my disapproval of this decision of the Board of Trustees.

During my junior and senior years at Princeton, I was chairman of the Wilson Society, a non-selective residential association of undergraduates and faculty fellows that had been created several years earlier as an alternative to the selective eating clubs to encourage diversity in its members. My leadership of this organization was my proudest achievement at Princeton, because the success of the Wilson Society led to important changes in social life at the University and the creation of the residential colleges. I remain fully committed to diversity and inclusion in my life and broader society, and enthusiastically support Black Lives Matter today.

Woodrow Wilson was a very imperfect man who espoused some very unfortunate racist beliefs and policies in his life as a public servant. His name was chosen for the Wilson School in recognition of his service as 13th president of Princeton and his achievements as President of the United States, especially his role advocating the League of Nations after World War I.

How far are we willing to go to damn the memory of imperfect leaders? Thomas Jefferson not only owned slaves, but fathered at least six children with his slave Sally Hemings. #Metoo should be demanding that the Jefferson memorial in Washington be renamed, citing the power differential between owner and slave. Franklin D. Roosevelt approved of the internment of Japanese citizens in concentration camps during World War II. Are these crimes not far worse than Wilson’s policies?

Illiberal Puritanism has taken hold of too much “liberal” thinking on our campuses today, and needs to be challenged vigorously. There is much selective outrage, inconsistency, and hypocrisy to be found. Freud once said that a man and his creation are not the same thing, and we would do well to remember this as we evaluate, criticize, and appreciate the creations and achievements of deeply flawed individuals.

Wilson’s name and achievements should be remembered and respected, along with those of Jefferson and Roosevelt.

Eric Geller ’83

5 Years AgoFeeble Excuses

Reading the various responses to the renaming of the Wilson School, it is striking how feeble the excuses are for retaining the name. Some argue out of sheer sentimentality, “that’s the way it’s been so it should stay that way.” Some argue his achievements outweigh his deficits, although as one writer points out even his international achievements have been controversial with problematic consequences. Some rail against “political correctness,” maligning the student body as snowflakes who need to be protected from anything troublesome, as if fighting for a change they believe in deeply against numerous odds is somehow weak. Some speak about reassessing naming rights of donors, but the school was named for him in honor, not financial contribution, holding him up as a role model for students and scholars. Some worry about a slippery slope that might lead to reassessment of other historical figures, as if that is somehow a bad thing. Some defend him and other racists as a product of their “times,” ignoring the fact that there were whites fighting for abolition since before the founding of the USA, and Blacks themselves have never supported their own oppression. Some feel the name gives continuity, even though clearly Wilson himself would be shocked and dismayed to see so many on campus who are not white men. Some complain about giving in to “mob rule,” but don’t explain why important decisions must be made only by a small handful of people in certain positions of power. Some cite the recommendation from five years ago to keep the name as eternal justification, as if a changing world should not affect anything (and in fact the world has not changed at all, we are just getting live video of it that we can’t ignore anymore).

President Eisgruber is in an impossible position. A university president must try to please all constituencies, but eventually a decision must be made. (Surely an enterprising archivist will be able to find alumni complaints about the changes Wilson implemented too.) If there are those who want to honor Wilson’s achievement in turning Princeton into a 20th century research university, perhaps the best tribute of all is to continue evolving the university to meet the moment and lead to a better future.

James W. Anderson ’70

5 Years AgoScholars’ Views of Wilson’s Legacy

Hearing of the decision to remove Wilson’s name from the Wilson School, I looked again at the 2015-16 review of the issue. I noted that background information was sought from nine experts, six White and three African American scholars. What struck me was the difference between the views of the African American academicians, whose position I thought should be prioritized, and the views of the White academicians. The three African American scholars all pointed out how malignant and excessive, even for the era, was Wilson’s racism. Five of the six White scholars, in one way or another, took a position similar to that of Professor Kendrick Clements: “Against a full understanding of Wilson’s racism (however that is defined), Princeton needs to weigh the whole of his public career….” I would paraphrase that as, “We ought to keep the name on the School; his heinous racism doesn’t matter that much because his accomplishments outweigh it.”

Sadly, Princeton, by retaining Wilson’s name in 2016, sided with that view. The University should have seen then, but fortunately recognizes now, how painful it would be for African American students to study at a School named for a person who, whatever his achievements, treated people like themselves as less than human and substantially injured them by his actions, such as taking the lead in kicking people of color out of Federal jobs. White people like myself who are undergraduate alumni of the School were forced to be complicit in that stand.

Chris Douglas ’88

5 Years AgoApplauding the Dropping of Wilson’s Name

Speaking as a former resident of Wilson College, a graduate of what was the Woodrow Wilson School, but also a member of an old abolitionist Hoosier family, I could not be more pleased at Princeton finally so awakening to the ignominy of Woodrow Wilson’s name as to remove it from places of honor.

Wilson’s racism should not so long have been dismissed by Princeton as those “of his time.” That is an insult to other men and women, also of his time, of greater character than he.

For instance, I think of my great grandfather, Maurice Douglas, a farmer, a businessman, and an Indiana State Senator who was then loudly opposing the Ku Klux Klan as it was becoming a major power in our state. A delegation came to him to ask him to run for governor with the condition that he drop his opposition to the Klan, which he declined to do. His opposition to the Klan was also the basis of his defeat in a run for Congress.

Woodrow Wilson was not just a lesser man who achieved high office, fame, and honors by doing that which better people of his time declined to do; he was a leader in driving his own day backward.

Meanwhile, men and women like Maurice Douglas die unknown to history not because at defining moments swimming against some tide they weren’t of greater character, but precisely because they were.

Norman Ravitch *62

5 Years AgoWrong Issue in the Wilson Case

I prefer to go with George Kennan, who in the late 1950s when I was in the Ph.D. program in history delivered an anti-Woodrow Wilson address at the very Woodrow Wilson School. His point was not about the racism of Wilson but Wilson’s disastrous role in the Versailles Peace Conference, where his naivete about democracy and the nation state eventually caused a certain Austrian low life, A. Hitler, to come to power in Germany and for a terrible six years in most of Europe.

Benjamin Lehrer ’03

5 Years AgoOn the Ethics of Naming

In light of the soul-searching the nation and University have conducted in its investigation of Woodrow Wilson’s racist legacy, every statue and building name on campus deserves the same examination. It is a privilege to have a building named for you on the hallowed campus of Princeton. Not everyone — not even Woodrow Wilson himself — automatically qualifies. Not by dint of power, political or financial.

As an architect with institutional clients that are dependent on bequests for capital building campaigns, the question of donor naming ethics has repeatedly arisen in our practice. While some gifts are given in the name of saintly community leaders, institutions often have us add multiple design features to entice an additional naming contribution.

Immortalization is the operative concept in the previous sentence. Civic buildings use sturdy materials to ensure they last more than 100 years. Why do donors expect their significant, timely contribution to last beyond the life of the building’s intended purpose? With each remodel, renovation, or expansion, the original gift effectively recedes back into history.

Donors have a right to be recognized for their outstanding gifts, but for how long? To stipulate that a condition for a gift is that its building bear a family name in perpetuity ignores the nature of posterity. Life changes, institutions change, and so must their recognition of generosity. It also ties Princeton’s hands behind its backs when it pursues avenues of expansion, as it does from time to time.

Certain criteria should determine whether or not a donor’s or luminary’s name deserves a place on every Princeton map — and they don’t solely include money given. One is demonstrated character (or alleged criminality, like the Sacklers’ opioid buildings at Harvard) and the other is demonstration over their lifetime of exemplifying Princeton’s values. If a Nobel winner is deemed unworthy of a name on campus, surely cosmetics magnates and Internet commerce tycoons with questionable scruples should be similarly vetted before the University lends its endorsement to the donors’ life’s work.

Why not name campus buildings for valedictorians, USG officers, Theatre Intime founders? Their most likely transgressions are binge drinking on The Street. If they go on to disgrace the University after graduation, a stable of worthy candidates stand poised to land their name on a building on the map.

All that said, maps benefit from stability and predictability the way buildings benefit from stolidity. All the more reason to examine with a fine tooth comb the potential building namesakes before they receive this enormous stamp of approval of their family’s and life’s legacy on Princeton’s glorious campus.

When a donor bequeathed a generous gift, they should not expect a naming plaque in return — they should expect the same sort of scrutiny that all applicants receive when trying to get into the freshman class of Princeton University. It is the ultimate privilege and honor, and we have the chance to rewrite history from the ground up, including our whole community, based on character and ethics.

John A. Gardiner ’59

5 Years AgoService and Today’s Princeton

As an undergraduate in the 1950s, I happily accepted the message of “Princeton in the nation’s service,” and linked it to the image of Woodrow Wilson as a committed public servant and advocate for international cooperation. Anticipating a career in law or public service, I was proud to be major in the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. I also became aware that Princeton was regarded as “the most Southern” of the Ivy League schools and was forced to acknowledge the anti-Semitic and racist nature of campus culture during the 1958 rebellion against the 100-percent bicker system.

At the time, I did not think of Wilson as actively racist, but rather simply as a man of his place (Virginia) and time. Over the last few years, however, the University’s dedicated exploration of its connections to slavery and its posture on civil rights and race relations has exposed Wilson’s deliberate efforts as president to enforce segregation in the federal civil service and otherwise to suppress minority rights. In light of these revelations, I strongly support the decision to remove his name from campus structures. Let us hope that the nation comes to see, instead, today’s Princeton as reflected in the service of Michelle Obama ’85 and Anthony Romero ’87.

Larry Leighton ’56

5 Years AgoNo Leader Is Without Sin

The great university that Princeton is today was initiated by Woodrow Wilson. Our administration and Trustees owe him that respect. He was also an esteemed president of the United States pushing for what would now be the United Nations. Woodrow Wilson’s name has enhanced the reputation of Princeton.

As a saying in the Bible about punishing a sinner says, “Let he without sin throw the first stone.” Wilson may have had a sin but who among our leaders are without similar sins?

Do we really now think that Harvard’s Kennedy School will strike the Kennedy name because of his serial sexual exploits? Or that Stanford will change its name because of his intercontinental railroads’ abuse of Chinese immigrant workers? I doubt it.

Instead of thoughtful, intelligent analysis becoming of a great university our leaders have instantly swung in the wind of the most recent social trend.

I am simultaneously outraged and saddened. This decision will distinctly harm the University.

I am embarrassed for our administration and trustees.

L. Marc Zell ’74

5 Years AgoTelling the Whole Story

An open letter to President Eisgruber:

Your message announcing the decision of the Board of Trustees and the administration just arrived (June 27). I am profoundly offended by this decision and the lack of fortitude demonstrated by the current University administration. I always believed that Princeton had more courage than to follow the herds of apologists for a national tragedy that occurred so long ago. It is one thing to acknowledge the dark side of American history. It is another thing to revise it and erase the names of the people who made that history.

The decision to erase Woodrow Wilson’s name from the school of public policy is also the height of hypocrisy. Will Princeton also dissociate itself from James Madison, a slave owner? What about Archibald Alexander (Alexander Hall), whose father was a Virginia planter and undoubtedly owned slaves?

Most of all, what about the anti-Semites Princeton has spawned or honored like F. Scott Fitzgerald (see Meyer Wolfsheim in The Great Gatsby), Breckinridge Long (proponent of the delayed U.S. response to the Holocaust), and, significantly, James Forrestal (virulent opponent of the establishment of the Jewish State after the Holocaust) after whom an entire University campus is named. And then there is Harvey Firestone whose name adorns Princeton’s world famous library. Here is what one author had to say about him and the notorious Jew-hater, Henry Ford:

“Neil Baldwin, author of Henry Ford and the Jews, recalls that Ford, inventor Thomas Edison and tire magnet Harvey Firestone used to go on motor-car expeditions to the hills of Appalachia and New England. Around their campfires, berating the Jews was a frequent practice. It was, as well, when pioneering aviator Charles Lindbergh and Ford became buddies.”

President Eisgruber, you yourself are Jewish halachically and by choice. Should Princeton also dissociate itself from these prominent but misguided men? As a former president of Princeton’s Hillel Foundation (1972-74), I might have standing to make such a request. In my day it was enough that Princeton dropped its numerus clausus for Jews especially from the Northeast. Still, I would not dare make such a request to revise the history of my alma mater by striking the names of these gentlemen and many more who I have not mentioned, as you and the Board of Trustees have done to Woodrow Wilson.

Let it be known that I am an active Republican and no great admirer of some of President Wilson’s policies let alone his despicable segregationist views, but as you mentioned he transformed Princeton and shaped the future of our nation and the world. He appointed the first Jew, Louis Brandeis, to the U.S. Supreme Court. Indeed, were it not for the Allied victory in World War I, for which Wilson is largely responsible, the State of Israel where I have made my home for the last 34 years would likely never have been born.

The stain of slavery is forever imprinted on the American experience. As a nation, we were able to put an end to this horrible institution through civil war and through our constitutional institutions. We must, of course, acknowledge the evil of slavery and work to obliterate its deleterious aftermath. As a nation, we have done a commendable job, although the work is not yet complete. Having said this, it is not necessary to purge the names and monuments to men like Woodrow Wilson and the anti-Semites mentioned above from our memory and from the memory of our progeny. To the contrary, when our children ask who Woodrow Wilson and these others were, we must remember to tell them the whole story: their achievements and their failures. That is what I would have expected of a great university like Princeton.

Lemoine Skinner III ’66

5 Years AgoGreat Contributions and Just Criticism

Renaming the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs and Wilson College was, I think, a mistake. Wilson was a great man, who made great contributions to Princeton, New Jersey, the nation, and the world. His views and actions on race were deplorable, and for these he is justly criticized. But so were those of Jefferson. This fault does not negate their virtues and achievements, and for these they are properly honored.

Paul Hertelendy ’53

5 Years AgoHonoring Edith Wilson

Few would quibble with removal of the name of Woodrow Wilson from the school and other public inscriptions of his name at the University in light of his prejudicial remarks and writings. I would propose an interim solution: As his wife Edith Wilson was the tacit U.S. president during his final post-stroke year in office, and as Mrs. Wilson had remained steadfast in ties to Princeton for decades thereafter — I had been privileged to shake her hand when she came to campus as guest of honor at a major on-campus convocation in 1953 — I would propose changing the name of the school from Woodrow to Edith Wilson immediately, on an interim basis, until such a time as a permanent name can be approved, either to hers or other’s. This would recognize her signal commitment supporting the University, her role as tacit U.S. president 1919-20, and her unique part carrying out the highest U.S. governmental role by a woman in American history, that at a critical postwar time to work to achieve lasting peace. (You may know that on the 2300 block of S St. NW in Washington, D.C., her home till her death in the 1960s, is now a museum.)

More research on names and backgrounds is clearly needed. But though Woodrow was a racist, I have yet to encounter any prejudicial statements attributed to Edith.

Nicholas Piacente ’13

5 Years AgoWilson’s Influence on University History

I find the decision to remove the name of Woodrow Wilson both appalling and hysterical. This irrational decision erodes the legacy of Wilson as the architect of Princeton as the modern university we have come to recognize as a world-class institution. Prior to the arrival of Wilson, the “College of New Jersey” enjoyed the status of a small liberal arts college in suburban-rural New Jersey, and the College was regularly the object of derision among American higher education. Wilson curtailed the influence of the Presbyterian clergy that had hitherto dominated University affairs. It was also Wilson, along with his predecessor James McCosh, who transformed the “College of New Jersey” into the Princeton we currently know, by enacting reforms and programs that enhanced the quality of a Princeton education, and thereby creating the Ivy League institution as we know it. If not for Wilson, the “University” very well could have remained a liberal arts institution, akin in contemporary terms to other elite though regional colleges, but by no means the peer of Harvard, Yale, Stanford, Columbia, Chicago, MIT, and the like.

Therefore, before we acid-wash the name of Wilson from the campus and the communal memory, I ask all alumni to reflect on the degree to which Princeton has shaped their identity, the extent to which the Princeton-name has procured opportunities for them, and all those occasions on which he or she has invoked the name “Princeton” to his or her professional, social, or economic benefit — and fully realize that this privilege and status owes to the accomplishments of Woodrow Wilson. After all, we could have been graduates of the College of New Jersey, at Princeton, instead of Princeton University. For all those disturbed by the Woodrow Wilson name, perhaps they should renounce their Princeton degrees to adequately demonstrate their dedication to social justice, lest they continue to associate themselves with an institution crafted, shaped, and operated in the shadow of Woodrow Wilson. While you’re at it, abolish the Graduate College, which Wilson championed over the objections of the Trustees and alumni. Let’s revert to the College of New Jersey! That’s the only logical conclusion.

Vijay Thadani ’76

5 Years AgoAnother Naming Suggestion