Princetonians in Government Service Face the Impacts of Federal Layoffs

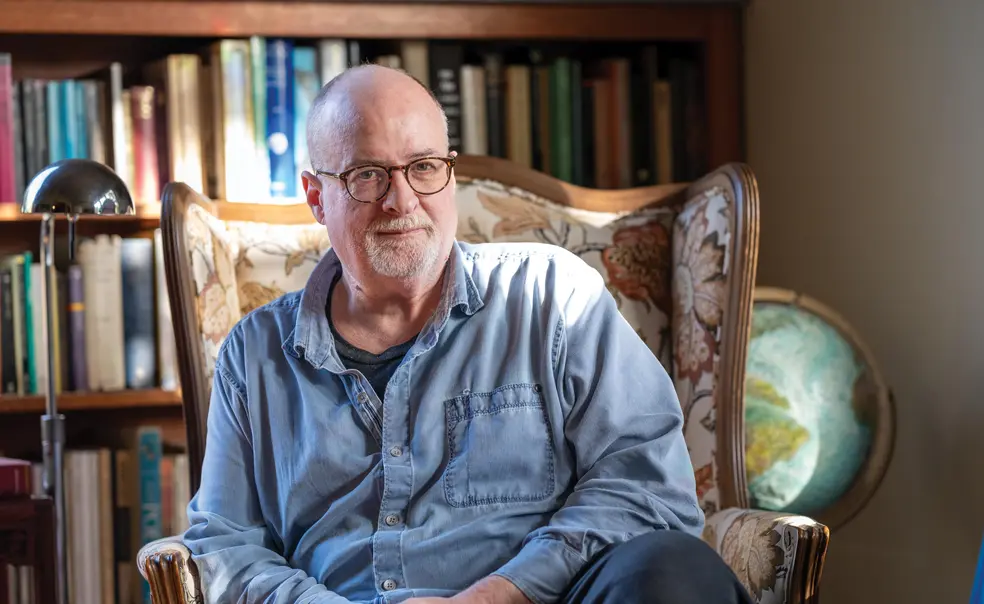

Until mid-march, Andy Artz ’03 was a supervising attorney at the Office for Civil Rights in the U.S. Department of Education. He had a mission for the past dozen years: to ensure schools that received federal funding were complying with civil rights laws, which prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, national origin, color, sex, disability, and age. But on March 11, his office was told via email that it was being shut down. “This wasn’t a careful review of efficiencies or of employee performance,” Artz says. “This was a blanket elimination of seven of the 12 offices.”

He immediately lost access to his work telephone or email and the ability to communicate with anyone external to the agency — putting his team’s caseload of 225 in limbo. Earlier that day, Artz was busy working those cases, with some of them close to being closed. Now he wonders what will happen — it’s not clear the cases will ever find a resolution, with just a handful of offices now responsible for processing all the cases.

“The most troubling part of this to me is that it appears the administration has decided that enforcing the civil rights laws is not something they intend to do,” Artz says. “It’s heartbreaking that it appears this administration is not interested in continuing that work.”

He’s not alone. Many Princeton alumni working in government service, from health officials to lawyers to diplomats working overseas, have lost jobs or are facing the threat of losing their jobs as a result of cuts by the Trump administration’s new Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), led by Elon Musk. DOGE’s stated goal of cutting spending and reducing the federal work force had resulted in more than 50,000 employees losing their jobs as of early April, alongside another estimated 75,000 who took buyouts. Some departments, including the U.S. Agency for International Development, have been gutted.

Cameron McKenzie ’19 worked as a community engagement specialist and a presidential management fellow for the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service as a probationary employee. When he opened his email on a Tuesday in late February, he found out his position had been terminated. “It was like a whirlwind,” he says.

McKenzie immediately thought of his husband, Eric Flora ’19, currently in his second year of law school. They had been relying on McKenzie’s steady government salary to make their mortgage payments.

A week later, he was back on the job when a court order reinstated probationary employees — but his future is still in flux. With the cuts, there is no longer a path to employment at the end of his fellowship. Work travel is restricted and in-person events canceled, so it’s been challenging for him to continue his professional development.

He’s also searching for jobs while tens of thousands of other former federal employees are flooding the job market, which makes his search more difficult. To help, McKenzie is putting his house up for sale and considering a move to Connecticut for a potential job opportunity — which would also come with a long-distance marriage for the near future.

McKenzie says the cuts to government agencies feel like indiscriminate slashing rather than efficiency. “If you want to know where the inefficiencies are, you need to talk to the people that are employed in the government, and we will tell you firsthand where they are,” he says. “There’s a right way to do it, and there’s the way that it is happening.”

Christian Crumlish ’86 was already working in government efficiency. Last year, the Silicon Valley tech worker joined 18F, an agency founded during the Obama years to recruit experienced technologists to help make government IT systems work better. Five weeks after the Trump administration took over, his entire team was fired. He says he felt both grief, and in a way, relief.

“I was pretty happy with the idea of capping off my career at 18F. It was my ‘Princeton in the nation’s service’ period, and that’s been wrecked,” Crumlish says. “But it’s a mission, and I’m going to try to stay on that mission and find a way to further it.”

Caroline Chang ’95 had only been working at the Department of Education since December — her role was to help keep some continuity as political appointees changed roles. She focused on services such as federal student aid and loan repayment.

On the evening of Feb. 5, she received an email that as of 6 p.m., she’d be placed on administrative leave. “Nobody came to talk to me,” she says. She walked to her boss’s office, but he had no idea.

Upset, but not completely surprised, Chang turned in her laptop and cellphone, and started to pack up her office. A security guard appeared at her door an hour later to tell her to leave. “It felt very unnecessary,” she says. “I was just bewildered at the way it was being handled. There was zero explanation.”

She has a theory about why DOGE was so interested in her office: They were setting up headquarters in the same suite and needed the space for their workers.

But in the end, she wants people to know that the impact of the cuts will be felt by everyone, eventually. “It’s not partisan,” she says. “It’s really a capacity issue. I would urge alums to pay attention because the capacity of government is really being fundamentally changed.”

Artz, the former Department of Education attorney, now spends his days attending continuing legal education courses, looking for jobs, and trying to keep up with his team. He still cares deeply about the work in civil rights and is actively looking into possibilities to continue.

“There is a lot of damage done to this country by portraying government workers in a light that assumes ineffectiveness,” he says. “In my experience, nothing could be further from the truth, and it will be a shame for this country to lose out on thousands of dedicated, smart people who have been working for the benefit of all of us.”

No responses yet