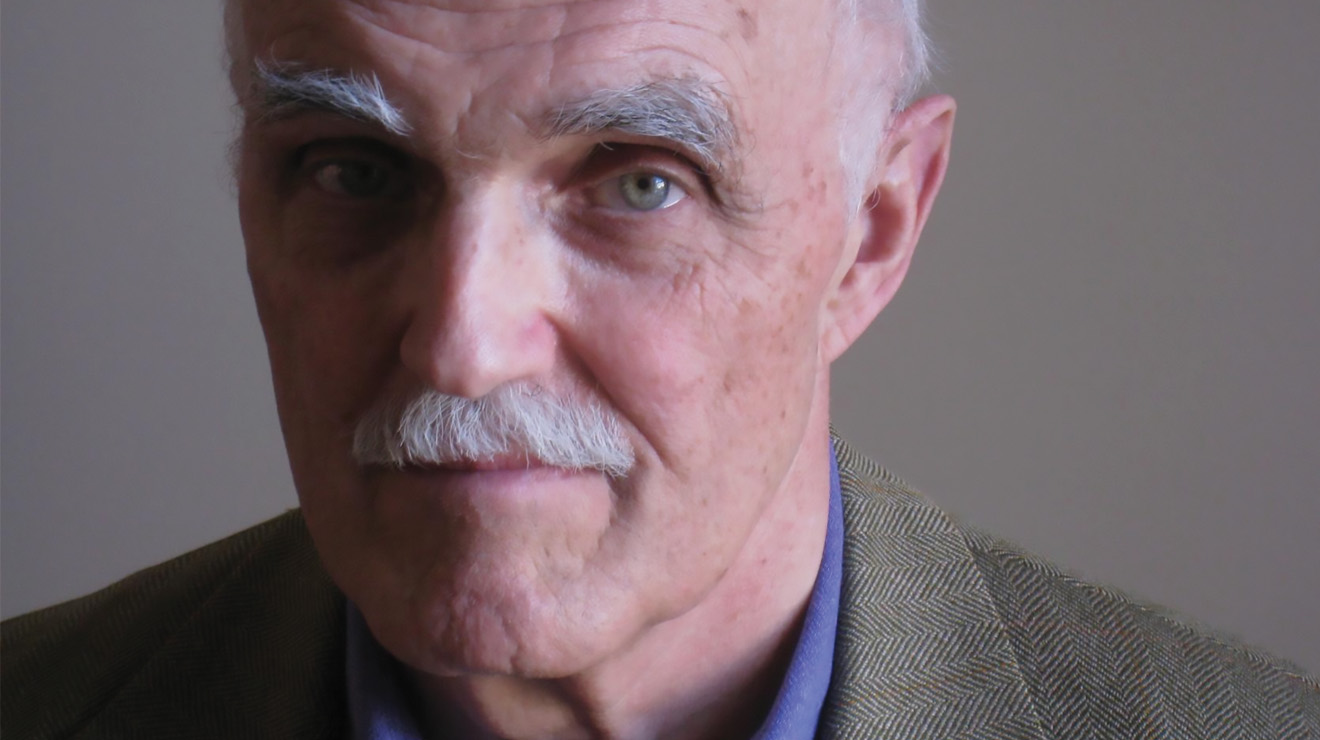

Publishing Giant Starling Lawrence ’65 Drew Great Books Out of Authors

March 11, 1943 — Aug. 21, 2025

I met Starling Lawrence ’65 38 years ago in his office at W.W. Norton, where he’d soon become the editor-in-chief. Norton was, and is, the last great book publishing firm owned by its employees. The people who run it are less inclined to spend money as it’s their money they’d be spending. The offices were less 1980s New York than Third Age shire — really just a bunch of hobbit holes filled with people still getting used to the invention of electricity. I was 26 years old and still working at the Wall Street firm Salomon Brothers. I’d arrived at Star’s office with sweaty palms and a strong desire to write some kind of book but very little evidence that I could actually do it. The offices calmed me down a bit. I mean, if people in these conditions could publish books, maybe I could write one. But what really put me at ease was Star. Because he was himself so at ease.

Later I’d often hear people describe Star Lawrence as an aristocrat. This was mainly because he’d gone to Princeton and had a courtly manner and wore bow ties and had inherited half of Connecticut. But what was genuinely aristocratic about him was his total indifference to conventional opinion. He could afford to ignore what other people thought, and he did. Talking to him — even when you’d just met him — you sensed that you weren’t being listened to by someone sizing you up in any conventional way. You were being listened to in some original way.

What I pitched to him in the winter of 1987 was basically a history of American finance. I had no real characters. I had no real story. I didn’t mention strippers on trading desks or swan farts or fat mortgage traders eating 20-gallon drums of guacamole or million-dollar hands of liar’s poker or really anything about my own experiences, except at the very end, as a kind of coda to the entire history of American finance. When I was done Star Lawrence — and Star Lawrence alone among U.S. publishers — bought my book idea.

Over the next year he then teased out of me a book that bore no relation to the book I’d pitched him. The history of American finance wound up on the cutting room floor. In its place appeared this bizarre hero’s journey crammed with all the funniest stuff I’d seen and heard while working at Salomon Brothers along with an explanation of what was going on just then on Wall Street. The editor had taken the end of my pitch and made it the beginning of a story.

Then the story was published. Liar’s Poker, it was called. Other people who were not Star Lawrence read it. The reaction shocked me. I know this might be hard to believe now, but I’d actually liked the characters I’d worked for at Salomon Brothers. But when my former employers read what Star had coaxed from me, they didn’t feel liked. They hired publicists to go after me. The CEO photocopied the book and handed it out to all employees so they wouldn’t go out and boost its sales. A week after publication I was so radioactive on Wall Street that I basically assumed no one who worked there would ever speak to me again. But in the bargain — a bargain Star Lawrence had somehow struck on my behalf — my name was on the cover of the country’s bestselling book.

There’s a mystery here. I don’t go through life looking to upset other people. But the minute I began to write a book for Star Lawrence I somehow acquired this fantastic ability to piss people off. Over the next 35 years this kind of thing happened again and again and again with us. Star would create this calm and measured mental space in which he’d tease a book out of me. (He teased out 17 in all.) The book would then be published and all hell would break loose. Eventually I came to understand what was happening: the Star Lawrence effect.

I think people have a hard time being themselves, especially when they are putting words on the page. They write in a defensive crouch. They worry about how others will react. They imagine their subjects’ feelings. At the pro level, they worry about reviewers and sales. Without even realizing that they are doing it, they censor themselves. I might have done that too — had I never met Star. But once I’d met him his voice silenced all the others. His voice said in so many words, “Don’t worry what anyone else thinks. If it pleases me, the rest will take care of itself.” And in the most amazing ways it did.

What was it about that voice — that it had this power? Well, for a start, it was totally sure of itself. Star could be impatient. He didn’t have time for jargon and complicated explanations that made the writer seem smart but made the reader feel stupid. He didn’t like it when you used more words than were necessary. And if you didn’t have interesting characters to describe, or a compelling story to tell, he felt a kind of pity for you. But if you could grab his interest, he had endless patience. Writing for him you felt that. That once you grabbed his interest, he’d let you take him anywhere.

That’s why, as an editor, he wound up in so many different places. True crime (Vincent Bugliosi’s Helter Skelter). Literary fiction (David McCloskey’s The Persian). Diet books (Martin Katahn’s The T-Factor Diet). The 20 volumes of Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey-Maturin historical fiction series. I don’t think he ever once looked over his shoulder to see where other people were going so he could follow. He had none of that kind of fear in him. That’s why as a very young editor he was able to fish James Grady’s Six Days of the Condor out of the Norton slush pile. And see the power of Burton Malkiel *64’s A Random Walk Down Wall Street. And be the only editor in the United States willing to pay money for Sebastian Junger’s The Perfect Storm — and for my own Liar’s Poker.

But he had something else. Whatever it is that allows a child to curl up with a book and become wholly absorbed in it — without the slightest concern of what he is supposed to think of it, or what other people think of it — Star still had that in him. He somehow got through boarding school and Princeton and rose to the top of American publishing without ever losing his capacity for simple delight. Sort of like he’d never really learned to clean his room. And the sound of his pleasure in my head was so much fun to write for that it’s the only voice I wanted to hear.

Michael Lewis ’82 is an author of New York Times bestselling books, including his most recent, Going Infinite.

2 Responses

Robert Morgan ’65

3 Weeks AgoPoignant Portrait by a Friend

Daniel Deitch ’65 or “Dan Douglas” is the photographer of the poignant portrait that accompanies the moving memorial. Star and Dan were veterans of the Triangle chorus line and remained lifelong friends. After Princeton, Dan attended the London School of Dramatic Art on a Fulbright followed by an A.M. at Harvard where he acted and taught at the Loeb before embarking on a stage, TV, and film career, including appearing in the original cast of Grease. These multiple talents morphed into a burgeoning NYC real estate career at Corcoran where he partners with his lovely wife Eileen. Credit where it’s due!

Edward Z. Walworth ’66

1 Month AgoAlso a Star on Stage

Great piece about Starling Lawrence. He was obviously a star in the world of publishing. He was also a star on the stage at Princeton, playing leading roles in Triangle shows.