Rally ’Round the Cannon: Destiny’s Children

Here I shall stand

Against misfortune, with its crushing hand,

And, though it crowd me to the lowest pit

Where I shall see no starlight in the sky,

Yet I shall struggle upward, bit by bit,

Until I see the white dawn drifting by.

— Grantland Rice, 1924

This marks the 100th anniversary of Princeton Football’s Team of Destiny. For those who don’t recall, they were a huge deal in an era with few other national sports fixations following the end of the baseball season; the Yankees’ Murderers’ Row was being built and was a year away from its first World Series win. You’ll notice both had catchy nicknames, and so we arrive at the real nub of our story: the ascendance of the media through the last century as illustrated by the sports pages, and the weirdly compelling adventures in which Princeton found itself participating as a co-conspirator in the festivities.

It all came together on Oct. 28, 1922, in the heavily hyped matchup in Chicago between intersectional gridiron rivals: independent Princeton, and Big Ten powerhouse Chicago. Yes, you read that right — the Maroon (when John D. Rockefeller builds a college, he copies from the “best”) went along with Northwestern in joining the huge Midwestern public colleges to encourage big-time athletics in 1896, the first formal conference in the land. This ostensibly was motivated by normalizing recruiting and playing rules, but by the 1920s it also served the purpose of providing reams of news copy across the country in which the relative prowess of the traditional football powers of the East could be compared to the Western teams and other pretenders widely scattered across the country. Already in 1922, Iowa had made the arduous journey to New Haven (after the corn harvest) to shut out Yale 6-0, to the outcries of the New York press and joy throughout the Midwest; Chicago indeed had done the same to Princeton in a packed Palmer Stadium the year before, 9-0.

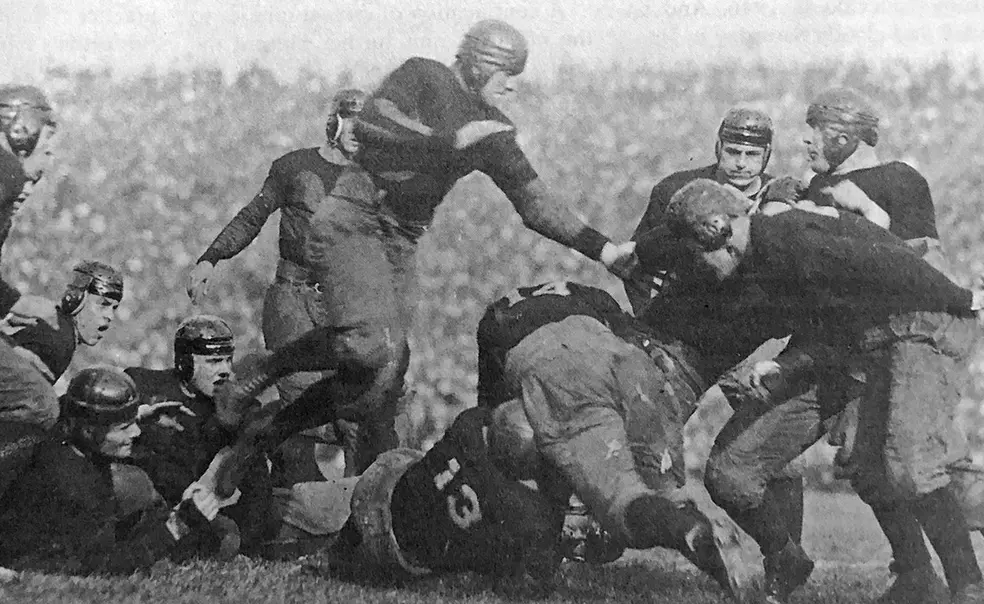

The Tigers’ road rematch was on campus at Amos Alonzo Stagg Field, demurely named for the active Maroon football coach, regarded as the great reigning genius of the game (with Knute Rockne of Notre Dame moving up fast on the outside). Bill Roper 1902 was Princeton’s coach; he still has more wins, 89, than any other in school history. Princeton was 4-0 having given up no points, Chicago 3-0 against stronger opposition, so each dreamed of an undefeated season. In the end, this would be the only game either would lose all year. Stagg was known as the brilliant innovator, but with a bigger, faster, more experienced team, he resolved to shove the ball down Princeton’s throat, while Roper, having been shut out the year prior, was convinced he needed every nuance of the playbook to survive.

The brouhaha drew a crowd, and then some. Stagg Field, with 32,000 seats, had 100,000 ticket applications. This was red meat to the aggressively competing newspapers of the day, of which there were a slew (rather than quoting dry statistics, imagine the palace Xanadu in Citizen Kane; this is when the construction of its model, newspaperman Willian Randolph Hearst’s San Simeon, was at its zenith). The Daily Princetonian, in its rabid zeal, ran 14 articles on the upcoming match in the week preceding the game. The New York Times, whose sports scribes presumably didn’t have to take time out for class, ran 17. Princeton staffers assured the public that wire reports would be available at the simultaneous freshman game on campus, which otherwise no one would attend. That was because, for the first time in history, the electronic giants were taking on the print giants nationally, and the multimedia world got underway. Westinghouse’s 6-month-old radio station KYW in Chicago was carrying the game; they were trying to sell their radio sets. Meanwhile, AT&T was trying to sell land line usage, and so ported the signal to their station WEAF in New York City, and then outward to any other city with an interest, which was pretty much everywhere. In Princeton, it was carried by Bamberger’s new WOR in Newark (trying to sell the Westinghouse radios), and every existing set in town (even the police station) was tuned to the game with a pile of hangers-on. A thousand people listened in Palmer Physics Lab, although that obviously was in multiple rooms as no lecture hall was that size. Hence the delirious celebration on campus began moments after the closing whistle by fans who felt they had been there, thanks to announcer Gus Falzer, the sports editor of the Newark Morning Call. The national live ad hoc network was touted in retrospect as the most important broadcast event in the world to that time. And so the global multimedia battle continues unabated.

The astounding punchline is that the event actually lived up to the hype. Chicago confidently marched down the field three times in the first three quarters to go up 18-7 (blowing all three extra points); the Tiger score was on a brilliant if desperate series of passes and counter plays in the first half. Princeton had the ball on its own 1-yard line to start the fourth quarter, passed out of trouble instead of kicking, then pounced on a Maroon fumble for a 40-yard TD return. This shook up Chicago, who couldn’t restart the jets, and Princeton got the ball back, put together another polyglot drive, and scored on fourth down with a few minutes to go to make it 21-18. Chicago got the kickoff on its own 15, marched to the Princeton 2, and with seconds to go was stopped on the 2-foot line by Pink Baker 1922, Oliver Alford 1922, and Charlie Caldwell 1925 — later to be one of Princeton’s Hall of Fame coaches. Then the Tigers punted out of danger. The New York Times called it “the most sensational intersectional battle in football history.” Grantland Rice in the New York Tribune referred to them later as a team of destiny as they proceeded to come from behind to beat Harvard 10-3 and sneak by Yale 3-0, with but five first downs, to become consensus national co-champions. This is not so much high praise as a bow to the mystery and chemistry of teams that win as distinct from teams that are good. The East/West rivalry intensified; the Harvard, Princeton, and Yale Clubs of Chicago built a joint clubhouse. Westinghouse sold piles of radios.

Seventeen years later, on May 17, 1939, it was RCA’s turn as it televised the first sporting event in U.S. history on its W2XBS in New York, mainly to its pavilion at the World’s Fair … to sell its TVs. The final baseball score in extra innings from Baker Field: Princeton 2, Columbia 1.

The print media had pretty much one last chance at sports impact, embodied in the creation of Sports Illustrated in 1954, and while that was coincident with the Ivies deemphasizing varsity sports by forgoing athletic scholarships, SI later did feature Tigers on the cover (including the Princeton Band and Bill Bradley ’65). Inside the magazine, Frank Deford ’61 led a slew of great Princeton writers.

But television continued to dominate and, with the rise of cable and then ESPN in 1979, ground down all in its path. That brings us emphatically to Pete Carril, who died in August after 92 inimitable years, following an impact that pervaded the University, snuck into multiple columns here, and resulted in an honorary doctorate unique among Princeton athletic coaches. The 49-50 Tiger basketball “loss” to John Thompson Jr.’s Georgetown in 1989 is universally regarded as one of the best tournament games ever played, one of the very few in the opening round, but that’s just one dimension. It also helped make billions of dollars for the NCAA and CBS, as college basketball accelerated its exponential growth.

Most crucially the tournament was saved for the Cinderellas including Carril (actually more of a Don Quixote) and that modestly-regarded young Princeton team of 1996 that clamped down on UCLA. The Gabe Lewullis ’99 layup that you know and love, covered by perhaps 12 CBS cameras, was much better quality videotape than anything from the simple coverage of ESPN seven years before, and so became an unavoidable part of Pete’s obituary. As you read the tributes and the breadth of his influence, you wonder again at the unlikeliness of his story (e.g. his only links to Princeton before he was hired were one year playing for Butch van Breda Kolff ’45 at Lafayette and a point guard he coached in high school, Gary Walters ’67). Were Grantland Rice around, he might well term Pete a Coach of Destiny.

1 Response

Roger Fingerlin ’69

3 Years AgoDon’t Forget This SI Classic

How could Gregg Lange ’70 omit mention of the Sports Illustrated cover of Feb. 27, 1967, featuring Gary Walters ’67 and Chris Thomforde ’69?