Time and Again, Jerrauld Jones ’76 Stood Up for Civil Rights

July 22, 1954 — May 31, 2025

Jerrauld C. Jones ’76 burst through barriers from the age of 7.

He was among the first Black students to integrate Ingleside Elementary School in Norfolk, Virginia, and later, Virginia Episcopal School in Lynchburg.

Jones faced a brutal welcome at both schools. He heard the N-word at Ingleside and found it written with shaving cream on the mirror of his room at Virginia Episcopal, where he also got beat up.

He didn’t back away. “He knew why he was there,” says Walter H. Riddick Jr., a friend since childhood. “Once he went across the threshold, there was nothing you could do to get him out of there.”

Jones didn’t talk about the abuse publicly — until Jan. 25, 1999. A Democratic member of Virginia’s House of Delegates, he rose to speak against a bill that would have authorized a Sons of Confederate Veterans license plate with an image of the Confederate flag.

He’d encountered the flag at both schools, but he first saw it at age 6, passing a Ku Klux Klan rally where people waved it next to a burning cross. “The fear in that bus was so great, you could smell it,” Jones told his fellow legislators. “All we could do was hope and pray that we would not be molested because of that symbol of hate and violence … . And now, some want to put that symbol of pain on the cars of Virginia.”

The House voted to drop the flag from the license plate.

“It was simply a mesmerizing speech,” says Kenneth Melvin, a former House member and retired judge. “He painted a picture so vivid that anyone could understand it.”

That moment illustrated Jones’ oratorical prowess and ability to build diverse coalitions. “Just about every member of the General Assembly thought they were personal friends of Jerrauld,” says Melvin.

Jones served in all three branches of Virginia government: After 14 years as a delegate, he became director of the state’s Department of Juvenile Justice and then sat as a judge for 19 years in Norfolk, first in Juvenile and Domestic Relations District Court and later in Circuit Court.

But his first love — and first source of income — was music.

His upper-class suite, 33 Blair, became known as “Club 33.” Charles Davis ’76, one of Jones’ roommates, recalls parties packing the place and music blaring out the windows, from Miles Davis to Funkadelic. Sometimes, there’d be impromptu performances with Jones on trumpet.

The Daily Princetonian called him “a joyful jazzman.” Jones, a sociology major, played in the group Anubis and belonged to the glee club, marching band, and gospel choir. The year after he graduated, he played at clubs in New York and New Jersey with Montage, a band made up mostly of alumni.

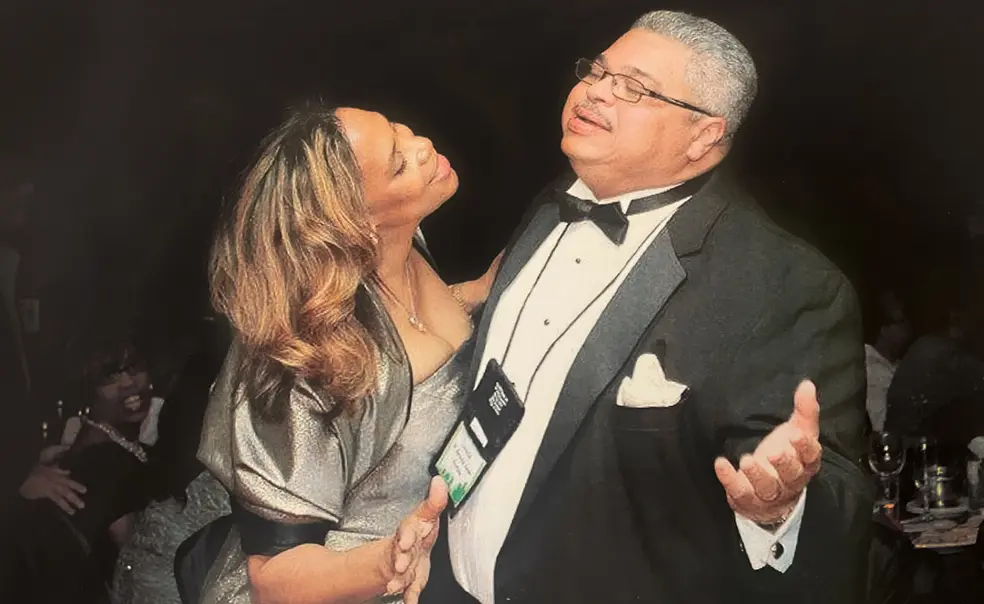

Though Jones stopped playing professionally, he retained his fervor for jazz. In his sitting room, surrounded by prints and photos of musicians, he once more blasted his music. “I have never seen him so happy as when he got to play or listen to jazz,” his wife, Lyn Simmons, says.

Jones’ father, Hilary, a civil rights lawyer who was the first Black member of Norfolk’s school board, died when Jones was at Princeton. “I do think he wanted to continue his father’s legacy and build upon his good name,” says Jones’ former law partner, Randy Carlson.

He attended Washington & Lee University’s law school and became the first Black law clerk at the Virginia Supreme Court. Jones worked in the Office of the Norfolk Commonwealth’s Attorney and then went into private practice. “We didn’t have corporate clients,” Carlson says. “We represented a lot of people who were really down and out.”

Jones was elected to the house in 1987 and served as chairman of the Legislative Black Caucus. Melvin remembers Jones’ push to appoint more Black judges. “Because of his leadership, all of a sudden the judiciary became more reflective of Virginia. And he did it without a whole lot of friction.”

In 2001, he lost the Democratic primary for lieutenant governor. It could have been worse. Jones had decided to pass up Reunions, which was the weekend before the primary. “He was moping around, and I said, ‘Jerrauld, just go,’” Simmons says. He didn’t regret it.

The next year, then-Gov. Mark Warner appointed Jones director of juvenile justice. Shauna Epps, a colleague in the department, says Jones supported her efforts to seek alternatives to detention for some juveniles. “He understood that family and environmental circumstances, how you were supported by your community or not, had an influence. But he was honest to the fact that you just weren’t going to be able to help some people. He wasn’t naïve.”

As a judge, Simmons says, “he made sure he had all the information he needed before he made that all-important decision. Lawyers would complain to me, ‘Your husband takes too long.’” When Jones did rule, he often displeased both attorneys, opting for neither the maximum nor minimum sentence.

“He was as good in private life as he was in public life,” Simmons says. After she was appointed as a juvenile and domestic relations judge in 2015, Jones sat in the back row her first day on the bench. “He was so happy I finally realized that dream.”

His son, Jay, says, “He was there for every basketball and soccer game, despite having a ton of demands from his legal and political career. He was a fantastic listener and gave great advice.”

Like his father, Jay Jones has become a racial pioneer, set to take office in January as Virginia’s first Black attorney general. “I think my father would be beaming with pride about that, given he was the first to do so many things himself over the course of his remarkable career.”

Philip Walzer ’81 is a retired journalist and magazine editor in Norfolk, Virginia.

5 Responses

Abbey L. Pachter

1 Month AgoAdvocate and Activist

Thanks, Phil, for introducing me to this important civil rights advocate and political activist. May his memory be for a blessing.

Burton R. Smith ’77

1 Month AgoFriendship Forged in the Jazz Ensemble

Jerrauld and I were the founding members of the Princeton University Jazz Ensemble (PUJE). In fact, it was Jerrauld who asked me to join, saying, “We’ll be the brothers in the group.” Jerrauld and I are in the promotional photo taken, and though he wasn’t at the inaugural concert at Alexander Hall in 1975, I knew only a family matter would have kept him away. I met up with Jerrauld at the 40th Reunion of Princeton’s Class of ’76 where I heard of his work as a judge in Norfolk. Our last conversation came by phone, right after the 50th reunion of the Jazz Ensemble. When we finally connected, we spent almost an hour on the phone, and I reminded him of how it all started with PUJE at Woolworth, how much his encouragement meant to me then, and how “guest playing” with Montage at Wilson College and on WPRB were “life moments” of my Princeton experience. Jerrauld told me then he was looking forward to attending his 50th in 2026. I kept this last phone greeting, “Hey, Burton, this is Jerrauld Jones calling from Norfolk ...” ♥

Indeed, Jerrauld’s life was a Blessing to all of us who were in his presence. Much Love to Jerrauld’s family and friends!

Aida Lupe Pacheco ’77

1 Month AgoFond Memories From Princeton and Virginia

I met Jerrauld as a freshman in 1973 and have such fond memories of him. We reconnected when I moved to Virginia in 1989. As the director of the Virginia Department of Juvenile Justice under Mark Warner, he called me out of the blue one day and encouraged me to serve on the Juvenile Justice Board. I told him I was not an expert and expressed reservations. But Jerrauld had a vision and such conviction to making a difference that I wanted to join his team. He convinced me that my areas of expertise in prevention and workforce development were needed. He also wanted to diversify the board and I became the first Latino gubernatorial appointee to ever serve. He led and guided his staff to focus on reentry efforts and together we were able to forge a partnership between Virginia's Juvenile Justice and Workforce Development systems.

Jerrauld was very close to his mother and was so very proud of his wife and son, Jay Jones, who inherited his amazing smile and passion for justice, and who recently became Virginia’s first elected African American attorney general. Sadly, Jerrauld did not get to swear him in, but I know he was with him in spirit and playing his trumpet.

John Weatherly Tinglin ’75

1 Month AgoHe Lifted Spirits

I remember Jerrauld as one of the most joyful people I have ever known. He was always ready with a smile or infectious laughter. Whether through his music or conversation, he had an ability to lift your spirits.

Leonard Alfred Mauney ’76

1 Month AgoRemembering Jerrauld Jones ’76

Lovely remembrance.