Big Dreams and Daring Marked the Life of Stockton Rush ’84

Princeton friends are mourning ‘Tock’ Rush, who died last week on a Titanic expedition

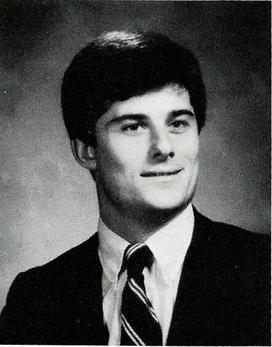

Friends are remembering Stockton “Tock” Rush ’84 as a dreamer and a doer, an intelligent innovator and rigorous scientist whose adventurous spirit showed itself during his years at Princeton.

Rush, 61, died last week after the missing submersible he had been piloting with his company, OceanGate Expeditions, imploded during a trip to the Titanic, killing all five people aboard.

“Charlie and I are mourning the loss of an irreplaceable, irrepressible, irreverent and fiercely loyal friend,” Eleanor Moseley Pollnow ’84 wrote in a statement with her husband, Charlie Pollnow ’84, who was Rush’s freshman roommate and remained close friends. “Stockton chose his path and pursued his dreams with passion. He loved and was loved. He lived the life he wanted — and it was a good life. A big life. We will miss him.”

Criticism has been leveled at Rush over the safety and structural soundness of the submersible Titan, but his friends say they’re grieving the kind and gregarious man who had an easy laugh and was prone to giving big, strong hugs at Reunions.

“Ask anyone in my Princeton University Class of 1984 which one of us would be brave enough to dare such a mission, and Tock would be at the top of the list,” Henry Payne ’84 wrote in a blog post about his friend. “Tock lived to conquer those risks. He — and his fellow passengers — died doing what they loved.”

The Titan was first reported missing on June 18 after communication with its expedition ship suddenly stopped while en route to explore the Titanic shipwreck nearly 13,000 feet below the ocean’s surface. A four-day search then began, with international support from Canadian and French search teams joining in the effort.

On Thursday afternoon, the U.S. Coast Guard announced that debris from the submersible had been found near the bow of the Titanic, and it was believed that the vessel had experienced a “catastrophic implosion.”

Seemingly round-the-clock news coverage of the missing submersible has led to some unfavorable characterizations of Rush as a risk-taker whose adventures trended toward recklessness. Deep-sea explorers, oceanographers, and other industry leaders were reported to have expressed concerns about OceanGate’s safety precautions in recent years. For example, the Titan was built of both titanium and carbon fiber, which is used in the aerospace industry but considered experimental for deep-sea pressure.

“I mean if you just want to be safe, don’t get out of bed, don’t get in your car, don’t do anything,” Rush told CBS Sunday Morning last year. “At some point, you’re going to take some risk, and it really is a risk-reward question. I think I can do this just as safely by breaking the rules.”

Rush’s friends said that quote has been used to misrepresent his “joie de vivre” outlook on life, and that the message of his quote was likely more along the lines of encouraging people to live their lives and not be afraid.

“History shows us that exploration and innovation are inherently risky and dangerous,” a group of alumni wrote in a statement to PAW, signing it “Proud and Grieving Friends of Tock.” “We’re disappointed, if not entirely surprised, at the outpouring of armchair quarterbacking about the science behind his work.”

Responding to reports of internal safety concerns at OceanGate, Rush’s co-founder, Guillermo Söhnlein, who left the company in 2013, told the U.K.’s Time Radio that there are many different opinions within the small deep-sea exploration community about how to design submersibles. “I know from firsthand experience that we were extremely committed to safety, and risk mitigation was a key part of the company culture,” he said.

Rush’s love for adventure was present from a young age. At 19 years old, reports say, he was the youngest jet-transport-rated pilot. His application to Princeton stated a desire to become an astronaut, but poor eyesight ended up foiling that goal.

At the University, he studied aerospace engineering and flew during the summers as a DC-8 first officer for Overseas National Airways in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. He requested to take off the fall semester in 1982 so he could keep flying during the hajj, the annual Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca that he called “the largest annual mass movement in aviation.” That request was ultimately withdrawn.

He kept a private plane at the Princeton airport, and friends recounted adventures they took with Rush at the wheel.

David Siebert ’81 said one of the greatest adventures of his life was a last-minute flight with Rush and two others to Cape Canaveral to see the launch of the Columbia space shuttle in April 1981. Rush flew them through the night in one direction, and through rain and turbulence in the other. “He just seemed calm and poised beyond his age; nothing really rattled him.”

Another friend who flew with Rush on his private plane during college remembered the feelings of trust and safety she felt on board. “He cared for people deeply and he wouldn’t want to put me in a position where I was unsafe.”

After graduation, Rush worked for the McDonnell Douglas Corporation as a flight test engineer. He served on the board of BlueView Technologies, was chairman of Remote Control Technologies, and was a trustee of the Museum of Flight in Seattle before founding OceanGate in 2009.

Rush married Wendy Weil Rush ’84 in 1986 and they had two children, Ben ’11 and Quincy. The Rushes have storied ancestors: Tock is descended from Declaration of Independence signers Benjamin Rush 1760 and Richard Stockton 1748, while Wendy is descended from Isidor and Ida Strauss, two of the wealthiest people to die on the Titanic. Ida famously refused to get on a lifeboat and leave her husband, and their story was incorporated into James Cameron’s 1997 movie.

Wendy served as director of communications for OceanGate and was on board the expedition ship during the Titan submersible’s mission. She declined to comment through a representative.

“Tock’s pursuit of his dreams was inspiring, his ability to live those dreams and his encouragement and his example helped others chase and attain theirs,” wrote the “Proud and Grieving Friends of Tock.” “He challenged himself to reach new heights and was constantly seeking the betterment of the earth and its oceans.”

“The world lost a wonderful adventurer,” Siebert said.

9 Responses

Christopher Chambers ’82

8 Months AgoThe Titan Implosion in Hindsight

With due respect to those alums, clubmates, etc. and his family who still mourn, it’s pretty clear in June 2025, with Coast Guard findings of fact, whistleblowers, and two damning documentaries, that what went on was darn near cultist and probably criminal had this happened with him on the surface. One also cannot dismiss the sociological element — of the bizarre “disruptor” craze, toys and myopathy of the wealthy. The others who died weren’t “mission specialists,” nor were they tourists. They were victims. There’s the lesson.

Gordon H. Hart ’70

2 Years AgoThe Titan Submersible and Engineering Ethics

As a Princeton graduate, through the years I have become accustomed to reading about the incredible accomplishments of many of my fellow alumni. In fact, being a Princeton alumnus is a fairly humbling experience. Therefore, it was with some shock when I read the article in The New Yorker by Ben Taub ’14 titled, “The Titan Submersible was ‘An Accident Waiting to Happen’” (July 1, 2023) and learned that the now deceased, former CEO of OceanGate, Stockton Rush, was not only a Princeton alumnus (Class of 1984) but also majored, as I did, in aerospace engineering.

All of us in society have learned of engineering disasters such as the Space Shuttles Challenger (in 1986) and Columbia (in 2003) as well as those that occurred before our time, such as the Tacoma Narrows Bridge collapse (in 1940, the video of which I first saw when I was an engineering student at Princeton) and, of course, the sinking of the Titanic (1912). The list goes on. Now the recent implosion of the Titan submersible (June 2023) will get added to that infamous list of engineering disasters.

I’ll let The New Yorker article speak for itself. Nevertheless, learning what we have about this recent disaster, it might be a good time to review the Code of Ethics of the National Society of Professional Engineers:

Engineers, in the fulfillment of their professional duties, shall:

1. Hold paramount the safety, health, and welfare of the public.

2. Perform services only in areas of their competence.

3. Issue public statements only in an objective and truthful manner.

4. Act for each employer or client as faithful agents or trustees.

5. Avoid deceptive acts.

6. Conduct themselves honorably, responsibly, ethically, and lawfully so as to enhance the honor, reputation, and usefulness of the profession.

As for Stockton Rush ’84 and the other now deceased occupants of the Titan submersible, may they forever rest in peace.

Ed Strauss ’72

2 Years AgoStockton Rush’s Forebear

Thinking about Stockton Rush ’84, I’m reminded of another tragic Princeton adventurer, Richard Halliburton 1921. Are there more?

Shawna Kent

2 Years AgoQuestioning Coverage of a Tragedy

I understand the personal loss experienced by friends of the man who led this expedition, but it seemed insensitive to publish a glorified account of who he was and not even mention the other lives lost because of him. I don’t think the world sees him as a hero — but rather as someone whose recklessness caused a tragedy.

Rob Hill ’84, Stephen Ban ’84, Jay Squiers ’83, Wistar Wood ’83, Taylor Gibson ’83, and Alan Barr ’84, on behalf of the Proud and Grieving Friends of Tock

2 Years AgoProud and Grieving Friends of ‘Tock’ Rush ’84

Stockton (Tock) Rush was our classmate, in many cases club mate, and in all cases, our friend.

We knew Tock as a joyful, gregarious, intelligent man with a wonderful sense of humor; a great friend; a loving husband. Someone who dreamed big and wasn’t afraid to chase those dreams. He and his family are famously generous; an object lesson in the notion that “to whom much is given, much will be required.”

Tock was a rigorous scientist, engineer, pilot, and explorer. Tock’s pursuit of his dreams was inspiring, his ability to live those dreams and his encouragement and his example helped others chase and attain theirs. He challenged himself to reach new heights and was constantly seeking the betterment of the earth and its oceans. OceanGate provides support for many true research expeditions at no cost.

History shows us that exploration and innovation are inherently risky and dangerous. We mourn the loss of our friend and the other crew members, and our hearts break for their families and friends.

We’re disappointed, if not entirely surprised, at the outpouring of armchair quarterbacking about the science behind his work. It has also been easier to predict failure than to lead the innovation and be willing to risk everything to push the limits of the human experience. In our grief over the loss of Tock, we found The Daily Princetonian’s story that highlighted his family history and some of the transgressions of his youth over his accomplishments inappropriate and, to a certain extent, mean-spirited. Tock was a hard-working student who excelled in the MAE program, was the world’s youngest commercial jet pilot, an F-15 test pilot, and an adventurer without limits.

As we collectively look back at cutting edge technological events, both positive and negative, that will never be forgotten (e.g., Apollo 11, the Challenger and Columbia tragedies, Lindbergh crossing the Atlantic) it’s extraordinarily impressive what Tock put together at his company of less than 50 employees and $37 million of funding. He creatively sought simpler solutions and didn’t/couldn’t spend billions on trying to figure out how to make things perfectly safe, if such a state even exists. As an entrepreneur, he embodied the spirit of innovation and thinking outside of the box.

In our lives we rarely meet someone who, on first impression, is so unique. Tock was a joy to be around; he made us laugh, he left us in awe, and we will always mourn his loss. We collectively hope that, when it is our time, we are remembered not for our weakest moments of judgment, but for living life as Tock did — one full of passion for everything new and interesting, and one that left absolutely nothing on the table.

David Wartofsky ’81

2 Years AgoSafety Obligations

From the letter: “As we collectively look back at cutting edge technological events, both positive and negative, that will never be forgotten (e.g., Apollo 11, the Challenger and Columbia tragedies, Lindbergh crossing the Atlantic) it’s extraordinarily impressive what Tock put together at his company of less than 50 employees and $37 million of funding.”

Fair enough. But Apollo 11 and the space shuttle disasters were scientific expeditions with only trained professionals as participants. Tock erred by selling seats on his undersea craft to the public. The public should not be subject to the same level of risk as a trained pilot or astronaut would be!

The minute he offered seats to the public, Tock became obligated to provide the highest possible level of safety. Since he didn’t do that, he was playing with people’s lives. This is inexcusable hubris.

David Wartofsky ’81

1 Year AgoTragic Losses and the Role of Risk

What happened to Tock Rush was a tragedy. And the points made by his friends, which imply that it’s OK to not make sure everything is safe as possible in such a venture, are misguided.

It would be one thing if Tock had only risked his own life through this cavalier carelessness. But he risked others also, and that is inexcusable.

Sandeep Mulgund *94

2 Years AgoA Disappointing Hagiography

Your biased hagiography of Mr. Stockton Rush was as fully predictable, one-sided, and disappointing as I expected it to be. Shame on the PAW for being more concerned with image than an unbiased accounting of a preventable tragedy brought about by hubris. One of the people you quoted stated: “Tock lived to conquer those risks. He — and his fellow passengers — died doing what they loved.” I’m curious, does that vapid assertion apply to the 19-year-old who forfeited his entire future because of Mr. Rush’s belief that he knew better than everyone else in the deep-sea submersible field? Would the folks lining up to defend their friend be so blasé if it had been their children or grandchildren had been pulverized in an instant two miles below the surface of the ocean?

Steven Schwartz p’15

2 Years AgoPrioritizing Safety

This is exactly right. Tock was reckless and careless with the most important aspect of a venture such as OceanGate: safety. It is a terrible tragedy for all involved, of course. But for the passengers — who were counting on the vehicle to have been as safe as possible — this is a loss of life that was preventable, had the attitude toward safety been less cavalier.