The Enduring F. Scott Fitzgerald ’17: Exhibit in Firestone Library Celebrates a Great Novelist

Next September, scholars and literary buffs will convene in Princeton to celebrate the centennial of novelist to celebrate the centennial of novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald ’17, one of the icons of 20th-century American letters. That same month, the U.S. Postal service will issue a stamp commemorating Fitzgerald. The author himself might have noted at least two ironies associated with these events. The first is that they are happening at all, for when Fitzgerald died in 1940, at age 44, he was a has-been, his reputation as a gifted chronicler of the Jazz Age undone by the Depression, booze, and the squandering of his talent in Hollywood. His famous observation notwithstanding, if any American life ever had a second (if posthumous) act, it was Fitzgerald’s.

The second irony is that these events honoring Fitzgerald are occurring only a month before thousands of alumni and friends of Princeton gather to celebrate the university’s 250th anniversary. The official Princeton has always felt a certain ambivalence toward its famous son whose first novel, This Side of Paradise, fixed in the public mind a picture of Princeton as a rich boy’s school, a place of lazy affluence dominated by the eating clubs and their snobbish pecking order. The country-club Princeton portrayed by the young Fitzgerald mocks Woodrow Wilson’s high-minded ideal—first expressed at the university’s sesquicentennial celebration, in 1896, the year of Fitzgerald’s birth—of Princeton in the Nation’s Service, and it scarcely reflects the meritocracy of today.

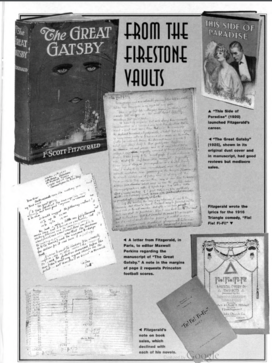

Whatever harm This Side of Paradise may have done to Princeton’s image, the university had long been a center of Fitzgerald scholarship. In 1950 the author’s daughter, Scottie Fitzgerald Lanahan, gave her father’s papers to Firestone Library, whose Fitzgerald holdings have been supplemented by materials from the publishing house of Charles Scribner’s Sons and other donors. This month and through September, Firestone will display some of these materials in a centennial exhibit, from which the photographs on this and the following pages are taken. The article is based on the exhibit text, written by Don C. Skemer, curator of manuscripts, and is supplemented by parts of the text, by A. Walton Litz ’51, for One Fine Morning, a video-tape on Fitzgerald’s life produced by Patrick H. Ryan ’68 (See page 62).

The Fitzgerald conference will be held on campus September 19-21. Sponsored by the F. Scott Fitzgerald Society, it will feature lectures, panel discussions, and reminiscences by friends of Fitzgerald. Those seeking more information should contact Anne Margaret Daniel GS, Department of English, Princeton, NJ 08544-1016 (609-258-4060).

The only son of an aristocratic father and a rather provincial mother, Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald was born in Saint Paul, Minnesota, on September 24, 1896, and attended the Newman School, in Hackensack, New Jersey, before entering Princeton in the fall of 1913. He thought of himself both as an heir to his father’s tradition (his namesake ancestor had written the “Star Spangled Banner”) and as the rough product of Irish immigration. Out of these mixed self-images would come his ability to see both the glamour and seaminess of American life. Fitzgerald was also a Roman Catholic, and like James Joyce, he never lost a sense of some innate depravity lurking under the surface of life.

Princeton admitted Fitzgerald “on trial,” and he never became much of a student. An English major, he had low grades, dropped and repeated courses, and was penalized for absences from class. Although never an intellectual, Fitzgerald fell under the influence of one of the great teachers of his era, Christian Gauss, who introduced him to European literature, and he was part of the campus literati that included the future critic Edmund Wilson ’16 and poet John Peale Bishop ’17, the model for the character Thomas Parke D’Invilliers in This Side of Paradise. (“D’Invilliers” was also the fictitious poet quoted later, on the title page of The Great Gatsby.) Working with manic anergy, the prolific Fitzgerald contributed plays, short stories, burlesques, poetry, and book reviews to The Nassau Literary Review and the Princeton Tiger, and he wrote the lyrics to Fie! Fie! Fi-Fi! And two other Triangle Club productions.

Health problems as well as poor grades led to Fitzgerald’s first withdrawal from the university, in his junior year. In November 1917, eight months after the United States entered World War I, he withdrew for the second and last time to join the Army. That same month he began writing This Side of Paradise, his coming-of-age novel about, as he put it, the “affairs of youth taken seriously.” A manuscript was sent the following May to Scribner’s. Editor Maxwell E. Perkins rejected it, but later accepted a revised version, which Scribner’s published in May 1920 and promoted as “a novel about flappers written for philosophers.” To the surprise of both its publisher and author, the novel became a runaway best seller. Although reeking of adolescence and seldom read today, This Side of Paradise remains “at once dated and ageless,” according to Fitzgerald Scholar James L. W. West, of Pennsylvania State University, “very much a product of its own times—the first (and still most faithful) chronicle of American youth in transition from the nineteenth century into the twentieth.”

The unexpected success of This Side of Paradise launched the 23-year-old Fitzgerald’s literary career and made it possible for him to marry Zelda Sayre, a beauty from Montgomery, Alabama, whom he had met while stationed at a nearby Camp Sheridan. The writer Ring Lardner, Jr., called Scott and Zelda “the prince and princess of their generation.” Their glittering lifestyle and well-publicized partying in New York and Paris and on the Riviera epitomized the excesses of young people who had, in Fitzgerald’s words, “grown up to find all gods dead, all wars fought, all faiths in men shaken.” But the marriage was soon bedeviled by Scott’s alcoholism and Zelda’s emotional instability. She was eventually institutionalized, and died in a fire at a mental home in 1948, eight years after Scott’s death of a heart attack.

In the early 1920s Fitzgerald completed two other full-length works. His second novel, The Beautiful and Damned (1922), is a moralistic and, some would say, prophetic tale about the decline and fall of Anthony and Gloria Patch, a contemporary American couple, who go from wealth and academic success to alcoholic ruin. Though it might sound a lot like what the Fitzgeralds’ life would become, his book was clearly influenced by Theodore Dreiser’s Sister Carrie and other American novels. Published to mixed reviews, The Beautiful and Damned became a best seller but failed to generate sufficient royalties to maintain the Fitzgeralds’ lavish lifestyle.

His third novel, The Great Gatsby (1925), chronicled the rise and fall of a dashing bootlegger undone by his romantic obsession for the rich and beautiful Daisy Buchanan. T. S. Eliot hailed it as the first important step in the American novel since Henry James, and it is generally considered to be Fitzgerald’s most enduring work. In The Great Gatsby, the author’s sensitivity to social nuances and moral scruples is brilliantly on display. It is the archetypal American novel of social ambition and the often tragic consequences of innocence betrayed, whether the paradise lost is a midwestern boyhood, Paris in the Twenties, or Gatsby’s platonic ideal of Daisy.

Although a critical success, The Great Gatsby had disappointing sales, and its author found it increasingly difficult to resist the financial temptations of writing short stories (some of them brilliant, other mere hack work) for mass-market magazines. He also turned to scriptwriting for Hollywood.

Fitzgerald was slow to come up with new ideas for novels that would match his literary reputation, and nine years elapsed before publication of Tender Is the Night (1934). Abandoning two early versions of the novel, Fitzgerald drew on his expatriate life to recast his book as the story of Dick Diver, an American psychiatrist who surrenders his youthful idealism in the pursuit of social advancement and betrays his talent for a life of “drink and dissipation.” In part, Fitzgerald drew on the painful experience of Zelda’s medical history to portray Nicole Diver, a mentally ill woman who marries her psychiatrist; Nicole’s hospitalization and eventual cure contributes to Diver’s personal and professional decline. Tender Is the Night, which went through 17 drafts and set proofs, received mixed reviews, in part because of its complex structure and confusing chronology. The critic Malcolm Cowley said there were really two Fitzgeralds: the man inside the great house taking part in the glamorous party, and the man outside, with his face pushed against the window pane. In The Great Gatsby the two come together brilliantly in its narrator, Nick Carroway, who is both a participant and a spectator. The problem with Tender Is the Night is that the theme and structure never quite join, and the novel is fractured down the middle by this split.

Fitzgerald attempted unsuccessfully to adapt Tender Is the Night for the movies. He had first visited Hollywood in 1927, and 10 years later he moved there permanently. Fitzgerald worked on M-G-M scripts for A Yank at Oxford, a comedy about an American Rhodes scholar, and for Three Comrades, the movie version of Erich Maria Remarque’s novel of the same name, and he contributed to the scripts for Gone with the Wind and many other films.

Fitzgerald tried hard to learn the craft of screenwriting but was unable to fit into the factory-style organization of the studio system. Although his mistress, the columnist Sheilah Graham, made great efforts to control his drinking, he was past help. By 1939 he was without a studio contract and worked as a freelance scriptwriter when he could find work. His boozing ended a brief collaboration with Budd Schulberg on Winter Carnival, a college film set at Dartmouth. Fitzgerald was also having difficulty writing good commercial fiction, despite the Pat Hobby Stories published in Esquire, and was reduced to submitting stories under a pen name. Dropped by his agent, Harold Ober, he became increasingly despondent. In the summer of 1940 he spent time aimlessly perusing the daily newspapers, circling items in the “personals” and advertisements for spiritual healing. He suffered a fatal heart attack on December 21, 1940, while reading a football story in the Princeton Alumni Weekly.

Fitzgerald’s Hollywood experience at least provided grist for his final novel. The Last Tycoon, which he was still working on at the time of his death, was loosely based on the career of M-G-M producer Irving Thalberg, and like so many other Fitzgerald works, its theme was the American Dream. A version of the novel was pieced together from Fitzgerald’s manuscript, outline, and notes by Edmund Wilson and published in 1941 as part of an anthology that included The Great Gatsby and five short stories.

Wilson’s effort marked the start of the long, posthumous rehabilitation of Fitzgerald’s literary reputation. A year later Wilson followed with a book version of The Cracked Up, Fitzgerald’s confessional essay, first published as a three-part piece in Esquire in 1936. The volume included laudatory evaluations of his work by Glenway Wescott, John Dos Passos, John Peale Bishop, and others. John O’Hara wrote an introduction for The Portable F. Scott Fitzgerald (1945). Malcolm Cowley, Alfred Kazin, Lionel Trilling, and other literary lions also contributed to Fitzgerald’s posthumous critical reception. Arthur Mizener ’30 wrote the author’s first significant biography, The Far Side of Paradise, published by Houghton Mifflin in 1949.

In a famous exchange described by Ernest Hemingway in his short story The Snows of Kilimanjaro, Fitzgerald once remarked, “The rich are different from you and me.” To which Hemingway replied, “Yes, they have more money.” Hemingway clearly thought he had gotten the better of the exchange, which in fact precisely defines the two writers. Hemingway, whose star in the 1930s ascended while Fitzgerald’s sank, was never interested in social distinctions and the nuances of manners. His style was suited to one man, alone, on the battlefield or in the bullring. It is a style that could never describe the world of Gatsby and Daisy. Fitzgerald, on the other hand, stands with Henry James and Edith Wharton as a master of the social scene, where money, manners, and social standing are the sources of action, the very fabric of reality, and the subjects of moral judgments. Of all the American writers of his time, F. Scott Fitzgerald can now be seen as the greatest chronicler of the world Gatsby dreamed of but could never obtain.

This was originally published in the May 8, 1996 issue of PAW.

No responses yet