On that unforgettable Friday afternoon, Nov. 22, 1963, grim news spread across campus: President Kennedy had been shot in Texas. University offices closed, classes were suspended, construction equipment fell silent at the half-completed New New Quad. The next day’s Princeton-Dartmouth game and Prospect Street parties were called off. So were performances at McCarter and Theatre Intime, and the movie showings at the Garden and Playhouse theaters.

At the Dulles Library of Diplomatic History at Firestone — a facility dedicated by former President Eisenhower 18 months earlier — a young employee, Charles Greene, was filing cards in a cabinet when he was distracted by secretaries in conversation. Soon one came over and told him about the radio report. Greene, who still works in that same section of the library, told patrons why the reading room was closing early. “They were appalled,” he says, as were so many others.

The Prince published a two-page special edition that included a list of campus mourning services, a statement from President Robert Goheen ’40 *48, and a black-bordered note from the editors calling for Kennedy’s death to “be taken as a rallying cry for the rule of law, of reasoned strength, most important, of unity — for which until Nov. 22, 1963, he stood.” Some students wondered aloud what would become of Kennedy’s civil-rights agenda; Professor Arthur Link, biographer of an earlier Democratic president, Woodrow Wilson 1879, predicted to the Prince that new laws would be passed quickly now.

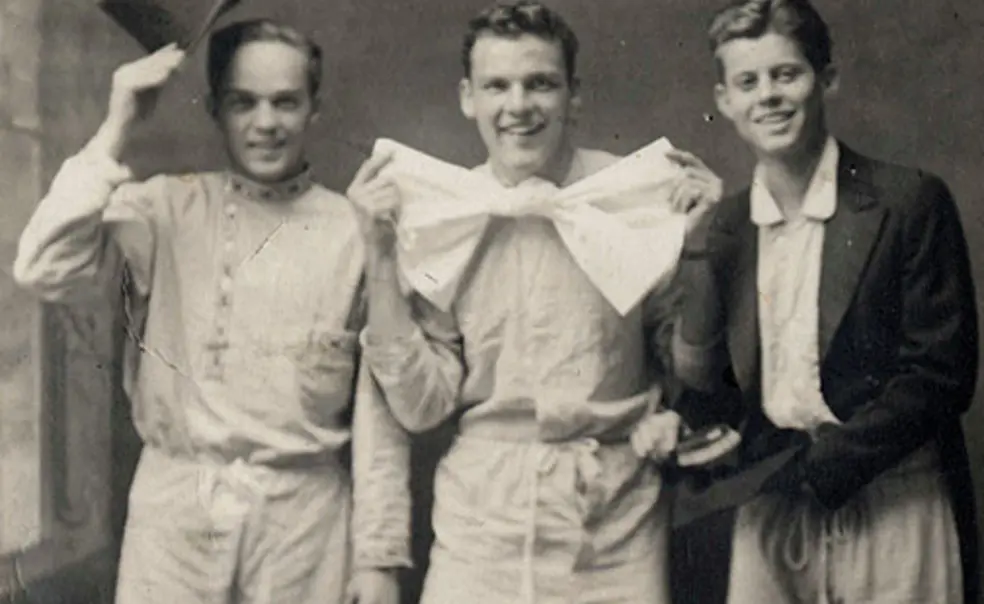

Many grieved for the dynamic Kennedy, who had spoken on campus several times as U. S. senator. Some shared stories of “Ken’s” brief tenure as a Tiger undergraduate in 1935 (then ill, he remained for less than two months). “It got too tough for me here,” he once joked, “so I transferred to Harvard.” Now Princeton mourned her former son.

No responses yet