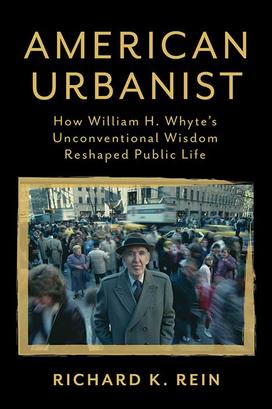

New Book Chronicles Urban Design Pioneer William Whyte ’39

Journalist Richard Rein ’69’s book chronicles Whyte’s impact

William H. “Holly” Whyte ’39 — journalist, author, urban anthropologist, and champion of pedestrian-friendly nooks in big cities — began his books with unadorned, declarative sentences. His 1956 bestseller, The Organization Man, starts: “This book is about the organization man.” His preface to The Exploding Metropolis begins: “This is a book by people who like cities.” At the Time Inc. business magazine where he first made his mark, he began an internal missive: “This memo is about Fortune; where it is and where it is going.” He coined the word “groupthink” in that magazine’s pages and, along with the Sloan Wilson novel The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, provided an enduring label for the conformists who nestled in suburbs and comfortable corporate niches in the 1950s. Yet he insisted that he never meant “organization man” as a pejorative but as a reminder that the vitality of any big entity — corporations, academe, churches, and more — depends on individuals thinking for themselves.

Whyte started out as an organization man himself, first in a cutthroat sales training program peddling Vicks VapoRub, then as a leatherneck lieutenant leading Marines in combat on Guadalcanal, and finally for more than a decade in Henry Luce’s Time Inc. empire — until Whyte, then Fortune’s assistant managing editor, walked away after being passed over for the top job.

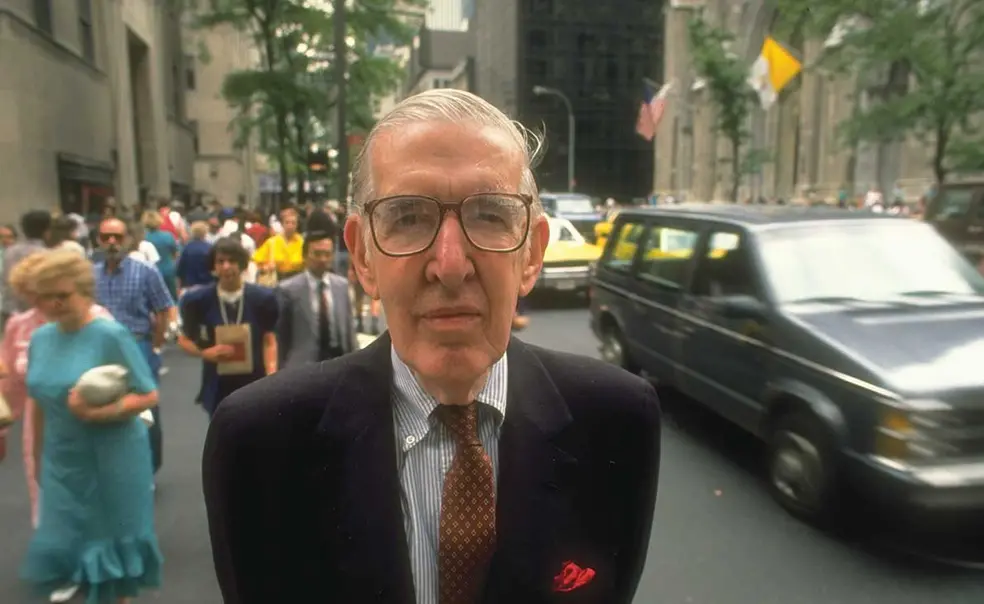

His life’s work was just beginning. He worked with patron Laurance Rockefeller ’32 to conserve open spaces and preserve the environment, then threw himself into making cities more livable, especially his three favorites — “New York, New York, and New York.” Through its downward spiral in the 1970s, he kept trying to make the city more hospitable for denizens and office workers alike. He devoted 10 years to his Street Life Project, setting up movie cameras on rooftops and deploying interns to chart which plazas attracted the most people, and produced a book and newsreel-style film on “The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces.” Meticulously he prescribed that plazas should be no more than 3 feet above or below the street curb and stairs should be at least 11 inches wide. He defended buskers and a bagpiper hounded by ticket-writers and had a soft spot for street people (“kooks and screwballs”), who he felt added to the spice of city life. He midwifed the rebirth of once crime-infested Bryant Park, insisting on movable chairs instead of benches so people could cluster or keep to themselves. (Rein writes that Whyte and Rockefeller tried to convince Princeton to put chairs on the plazas outside Firestone Library and around the School of Public and International Affairs fountain, but were told too many were stolen. Today there are some chairs and tables on the Firestone Plaza.) He offered advice on a 1980s expansion of Palmer Square and the development of the Carnegie Center on Route 1.

He defended buskers and a bagpiper hounded by ticket-writers and had a soft spot for street people (“kooks and screwballs”), who he felt added to the spice of city life. He midwifed the rebirth of once crime-infested Bryant Park.

Raised in prosperity in West Chester, Pennsylvania — another small college town that, like Princeton, would stave off suburban competition — Whyte was admitted to Princeton with three Ds, a D+ in English, and a B in sacred studies. The headmaster of St. Andrew’s, a fledgling prep school in Delaware, wrote an extraordinary letter of recommendation for the “brilliant & versatile boy” too busy with extracurriculars to make “a fair showing scholastically” but who’d “made a special contribution to the school from the funds of his particular genius.”

Whyte rowed at Princeton, penned short stories for The Nassau Literary Review, and wrote a play staged at Theatre Intime. The prep school kid showed mettle in the jungle on Guadalcanal but also honed a capacity to make sense of confused shards of information from battles and became an intelligence officer. His analytical Marine Corps Gazette clippings helped him secure the job at Fortune, the luxe monthly that afforded writers months to decipher how businesses were run and discern societal trends. A 1952 article on groupthink spawned The Organization Man, and a 1958 series on urban planning led to The Exploding Metropolis. Whyte was editor and champion of then-little-known Jane Jacobs, who expanded her “Downtown is for People” chapter into the classic The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

Ill health slowed Whyte down in his last decade, and he died in 1999 at age 81. He confided to his wife, fashion designer Jenny Bell, a fear his work would be forgotten. His influence resonates today with “new urbanist” planners and architects including Andres Duany ’71 and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk ’72. This “marvelous” biography, as a New York Times reviewer called it, will surely earn Whyte new disciples.

No responses yet