Pink Floyd Symposium: A Scholarly Look at an Iconic Band

In January 1967, an announcer for the Canadian Broadcasting Corp. alerted listeners about a new band called Pink Floyd, whose music threatened to push aside the Beatles with its “psychotic sweep of sounds and vision.” More than four decades later, Pink Floyd is widely regarded as one of the most influential rock groups in history, creators of iconic albums such as The Dark Side of the Moon and The Wall, and recently the subject of the first-ever academic conference devoted to the band and its music.

“Pink Floyd: Sound, Sight, and Structure” was the title of an interdisciplinary conference April 10–13 organized by two music department graduate students: Gilad Cohen, who is writing his dissertation on the group, and Dave Molk. The conference included a jam session at Small World Coffee, a film screening, a world premiere of new surround-sound mixes of several of the group’s works, and live performances of Pink Floyd songs, one by a string quartet.

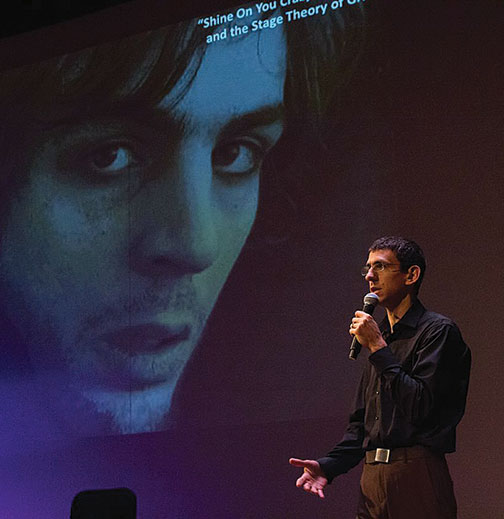

Several lectures gave the weekend an academic dimension, including one by English professor Nigel Smith on “The Genius of Early Floyd,” and another in which Cohen argued that the structure of the 1974 composition “Shine On You Crazy Diamond” tracks the five-stage Kubler-Ross model of grief. James Guthrie, Pink Floyd’s award-winning sound engineer, delivered an entertaining keynote address.

Cohen and Molk credited Scott Burnham, the Scheide Professor of Music History, and music department chair Steven Mackey for being receptive when they proposed an academic conference on the group. “They said, ‘It’s a gas!’” Cohen recalled.

Odd though it may seem to those either too old or too young to remember the band in its heyday during the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s, Pink Floyd “changed the way we listen to music,” Cohen explained. Where many of the group’s musical contemporaries shot up the pop charts with three-chord toe-tappers, Pink Floyd “tried to do something different,” experimenting with avant-garde arrangements and revolutionary sound-processing techniques that have influenced other musical genres. “They were interested,” Cohen says, “in art for the sake of art.”

No responses yet